According to the usual logic, terror is an instrument of oppression used by authoritarian powers to subjugate the population and reinforce their hold on public opinion. In Haiti today, terror is not used to consolidate power, but is a consequence of the absence of power. The loss of the monopoly of legitimate violence has led to a dispersal into the hands of venal individuals of the regal function of ensuring the security of citizens. At the same time, the oppressed strata of society, who have long suffered from social and cultural exclusion and an unequal distribution of wealth, are faced with a sense of disenchantment that has given rise to antisocial and violent movements: gangs. Their firepower is such that the state is unable to defeat them.

Assassination, impunity, and fear

On July 7, 2021, President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in the presence of his wife and children. According to witnesses, the victim was tortured before being shot dead with an automatic weapon: twelve bullets for one man. It could be the title of a B movie. Adding to this outburst of violence is the appalling ease with which the killers were able to escape with no bother at all. It was only when they returned to their bases that the perpetrators were apprehended. Clearly, they felt so confident of their impunity that they did not hide or even conceal their weapons. How did they manage to enter the presidential residence without encountering the slightest obstacle? This question is just as important as the motive behind the crime. The assassins were able to enter and leave the President’s residence without causing any alarm or reaction from the agents responsible for the head of state’s security. The execution was a mafia-style operation, which also acted as a warning for witnesses to keep a low profile.

Questionable elections, constant clashes, and the breakdown of law and order

At the time of his assassination, President Moïse was already an unloved figure. Elected in 2016, he took office after an electoral process marked by numerous irregularities, forcing the Provisional Electoral Council (CEP) to go back to the drawing board twice. The CEP, which was accused of corruption and massive misappropriation of public funds under the Petrocaribe program, continues to influence government decisions, and is seen as a stand-in for the presidency. Sporadic demonstrations have taken place to demand accountability in the use of public funds allocated for rebuilding the capital after the earthquake of January 12, 2010, which caused material losses with a value estimated at over $9 billion and left more than 250,000 people dead or missing.

The demonstrations generally start out from the capital’s poor neighborhoods and spread to the affluent districts of Pétion-Ville, where the people with money and power reside. Although at first they are peaceful, the protests often degenerate into ransacking of stores, looting of warehouses and acts of vandalism often targeting street vendors.

Between 2016 and 2018, Port-au-Prince experienced clashes between demonstrators and police, during which exchanges of gunfire left many anonymous victims dead. Meanwhile, the murdering of opponents does not result in arrests or any form of trial of the perpetrators. The head of state, himself a proponent of strong-arm tactics to get rid of his opponents, would eventually perish by the sword that he had used to suppress demonstrators in the streets. Power that relies solely on the services of outside infiltrators and obeys no democratic mandate to maintain public order, is doomed to disappear. The use of militias and criminal gangs to maintain law and order reflects a drift towards a mafia style of governance that has gradually led to drug smugglers taking the lead in operations designed to demonstrate the authority of the state.

Riots, gangs, and murder on demand

To ensure the safety of government personnel and secure the most important routes around the country and points of entry (ports, airports and border crossings), the use of private service providers has served as a Trojan horse for arms dealers, who have been able to move in all the more easily since the Haitian army was disbanded in 1995. In March 2018, a massacre took place in La Saline, one of the capital’s most deprived neighborhoods and the starting point for many anti-government protests. More than 80 people were murdered by gang leader Jimmy Chérizier’s henchmen. Some were butchered and grilled, retrospectively justifying the nickname of “Barbecue” that Chérizier had been given back when his mother sold grilled sausages on the city’s sidewalks. To date, no arrests have been made, nor has there been any public inquiry, while the victims’ relatives keep silent, for fear of reprisals.

In July 2018, protests intensified, and the government was faced with riots and barricaded streets. Despite the general discrediting of the state and the week-long blockade of the capital’s main roads, the government managed to hold on to power, but at the cost of a bloody crackdown orchestrated by the gangs. In poor neighborhoods, macabre scenes proliferated. Civilians found themselves at the mercy of armed gangs who murdered, raped and set fire to dwellings without any intervention from the police. Between 2018 and 2021, opponents of the government were systematically murdered, with no consequences for the perpetrators. Monferrier Dorval was assassinated on August 28, 2020, and Antoinette Duclair on June 29, 2021. The former was a lawyer and President of the Port-au-Prince Bar Association who was an expert constitutionalist and contested the legitimacy of the President’s proposal to amend the constitution by referendum. The latter was a journalist who was critical of the government. Both were assassinated in circumstances that remain unclear but suggest that it was by order of the Palace.

This is the backdrop against which President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated. Ariel Henry, as Prime Minister, took the reins but his power was immediately challenged by supporters of his predecessor who had been dismissed just two days before the murder. From July 2021 until his downfall in February 2024, Henry’s government watched helplessly as 80% of the Port-au-Prince Metropolitan Area was taken over by armed gangs in a criminal alliance called “Viv Ansanm” with a firepower totaling over 600,000 combat weapons. Jimmy Chérizier, who rules this cartel of mobsters with an iron fist, launched his first attacks against the central government in January 2024. To justify his actions, the gang leader adopts pseudo-revolutionary language. While wreaking havoc in the capital’s poorest neighborhoods (Bel Air, Delmas, Grand Ravine, etc.), the bandits claim to be defenders of the oppressed.

The rise of the warlords and the Presidential Transitional Council

Faced with the authoritarian drift of an ineffective and corrupt government, a section of the opposition chose February 2024 to call for the Prime Minister’s resignation. When heavy-handed police intervention failed to discourage the demonstrators, private militias were brought in to assist the forces of order. The government uses militiamen as auxiliaries who follow no code of conduct, much less any code of honor. The militias commit massacres in poor neighborhoods and drive the desperate inhabitants out of the areas under their control. Now acting as soldiers with no masters, former gang leaders have turned into warlords, laying down their own law in the outskirts of the city. The names of Izo, Lanmò Sanjou, Tilapli, Chen Mechan and Barbecue have become as familiar as those of key government ministers. Meanwhile, the government is gradually losing control of the gangs it has helped to establish.

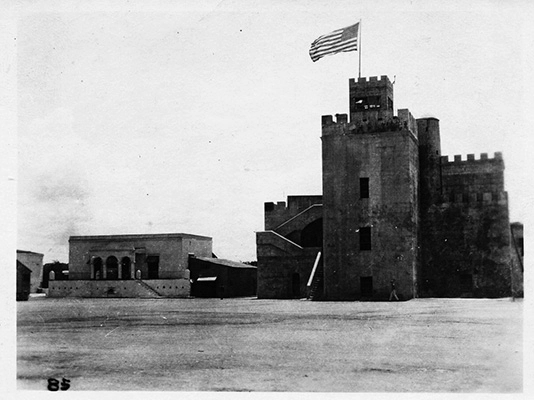

The gangs stormed symbolic centers of power, giving rise to fears that Barbecue might take over the national palace. The destabilization of the state was such that armed bandits prevented the Prime Minister from returning to Haiti after travelling abroad, and he was forced to resign. His defeat, besides offering an opportunity to remove incompetence, reflected the collapse of the authority of the state. This explains why Barbecue, in his public statements, is now demanding direct participation in power within the framework of the Presidential Transitional Council set up on April 30, 2024. His pseudo-revolutionary rhetoric resonates with some young people who have become disoriented by the drift of political power towards criminality.

A nation adrift

The degree of disillusionment is commensurate with the scale of inequality and the difficulty in finding a solution to extreme wealth disparities. Some 20% of Haiti’s population concentrates 65% of national wealth, while the poorest 20% share only 1%. It is as if the time for revolution had come, but the majority refused to join the movement, leaving a minority of zealots to express their rejection of an unequal and cynical system with both words and fire. The working masses from the suburbs, too preoccupied with their day-to-day survival, have no time for demonstrations. As for the middle class, wiped out by exile (with 85% of those holding a Master’s degree or higher degree living outside the country), it has not joined the protests either, for fear of the violence perpetrated by an infuriated mob.

From its position of systemic precariousness at the top of a social pyramid dangerously swollen at its base, the oligarchy is increasingly confused with an underworld with which it associates in order to continue to exist. Many businessmen and politicians (including senators and deputies) are involved in trafficking of all kinds. Whether on the land border with the Dominican Republic, the sea border with Jamaica, or the air border with the continental Caribbean states (Florida, Colombia, Panama), Haiti is at the center of a network linked to the illicit arms and drug economy. This network has ended up taking root in the political, economic and social fabric of Haiti, to the point where it has infested the public arena.

Comings and goings, and remaining outside

The Armed Forces of Haiti were disbanded by President Jean-Bertrand Aristide on his return from exile in 1994. After a decade marked by an increase in violence, the country enjoyed a relative period of calm between 2004 and 2017, thanks to the presence of a UN mission. MINUSTAH, with over 10,000 soldiers and police officers, contributed to pacifying the capital’s most troubled districts, but at an often-bloody cost. The “pacification” carried out by the Brazilian military police in particular has left its mark on memories and walls. The National Police, which could count on only 10,000 serving officers in 2018, is said to be down to just 7,000 due to defections of personnel attracted by the facilities temporarily offered by the US government for visa-free emigration to the United States.

There are reportedly several hundred gangs in the Port-au-Prince Metropolitan Area. In February 2024, they federated under the banner of Viv Ansanm, headed by Jimmy Chérizier (aka Barbecue), and as I have said, stormed the seats of power. After attacking the national penitentiary, freeing several thousand inmates, including criminals serving long prison sentenced, they went on to attack schools, police stations, churches, libraries and temples. They literally came to a halt at the palace steps, as the Champ de Mars, the heart of power in the capital, became a battlefield, literally and figuratively.

The “outer country” (that is, the provinces) is relatively untouched by gang violence. Unlike the capital, where it’s easier to go unnoticed, in the provinces, neighborhood vigilance remains a barrier to the expression of certain antisocial tendencies and crime finds a hostile breeding ground as community solidarity still works against intruders.

Shanty neighborhoods have become lawless areas, where racketeering, theft and rape have become the rule. The urban exodus has emptied these neighborhoods of their inhabitants, who seek refuge in the provinces.

The more affluent neighborhoods have not been affected, but the wealthy remain on the alert: they are the target of hostage takers who lie in wait for them along the main roads.

In this context, no country seems willing to provide assistance to Haiti, for fear of being dragged into the spiral of violence that seems to be sweeping the country away. The Dominicans, who are most directly threatened, are building more than 160 kilometers of wall on a border just over 370 km long. The Cubans are out of the picture, because of the US embargo imposed on their country since 1962. The United States – the only country in a position to significantly influence the situation – is doing nothing to stem the arms trafficking reaching the country from Florida. As I have said, there are reportedly over 600,000 combat weapons in circulation in Haiti. The US opted instead to call on Kenya to lead the peace mission, which the UN can no longer take on due to the lack of Security Council consensus.

In the face of globalized crime, Haiti stands on the front line of democratization. The country is left alone to deal with mafia-like networks and criminal associations, which have strong footholds in Florida, South America and on the island of Hispaniola. They also have the capacity to mobilize financial and human resources that the state lacks.

Disenchanted solitude

Underlying the sporadic unrest that marked the end of Jovenel Moïse’s term of office is the profound exasperation of a population mired in structural misery. More than a third of the population lives below the poverty line. Remittances from the diaspora, amounting to $4 billion a year, provide for the most basic food needs, but the country does not produce enough goods or services to do without official development assistance, which accounts for a third of the government’s budget. The state survives thanks to this double infusion of migrant remittances and budgetary aid from friendly countries, but at a time when international donors have other priorities to push, its lot does not look bright. Increased inflation in the period 2010-2020, and the resulting erosion of purchasing power for the poorest, have thrown the most vulnerable onto the streets. Young people from the underprivileged neighborhoods of Cité Soleil, Canaan, Pernier and Carrefour, lacking education and prospects for the future, have fallen prey to radicalized politicians who use them as human shields in the most violent demonstrations, and to gangs who recruit them to commit the most brutal acts of violence.

In the dialectics of class struggle, the marginalized have, on a territorial level, won the battle. Thugs, who already controlled the poorest neighborhoods of the capital, have extended their hold over the city center and the main traffic routes to the provinces, covering more than 85% of the Port-au-Prince Metropolitan Area. The collapse of the state is the result of this criminal logic. Taken to extremes, terror as practiced and staged on social networks by the gangs has led to a collapse of the rule of law in Haiti.

Jean-Marie Théodat, PRODIG (Research Center for the Organization and Dissemination of Geographic Information), Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, France <Jean-Marie.Theodat@univ-paris1.fr>