Brief Cartography of Latin American Sociological Associations

March 14, 2025

In recent decades, sociology as a profession has expanded in terms of the numbers and quality of graduates in various fields and roles in society. The expansion of the social question in the face of recurrent economic crises or the persistence of structural inequalities that have fragmented the social fabric, together with the emergence of new social actors, have led to new demands for social research. This article addresses the development of sociology from the academic to the professional field in Latin America through a comparative analysis of sociological associations in the region, their characteristics, and evolution.

A shaky beginning

The institutionalization of Latin American sociology proved to be difficult and was marked by various tensions. These included reservations concerning the promotion of social research, the need for academic autonomy, public commitment, and the internationalization of scientific life.

Academic development initiatives date back to the mid-twentieth century, marked by winding paths with various institutional obstacles, diverse rhythms, advances, and setbacks. Latin American sociologists began their practice in a traditional university framework dominated by a foundational matrix of universities oriented to the formation of classical liberal professions. Brazil exhibited a different trajectory, with later university development that was accelerated by the adoption of the North American model, with Institutes of Philosophy and Human Sciences and departments for research development. Across the continent, sociologists developed an academic practice whose goal was not exclusively the teaching and training of professionals but the practice of social research according to the criteria of the scientific method.

The development of sociology as a scientific discipline was closely linked to a university model of the Latin American reformist tradition characterized by political commitment and the defense of university autonomy in relation to governments. Thus, the historical legacy of the social sciences and their context combined rigorous social research with an activist tradition of resistance to the established social order, particularly in the face of the persistent authoritarian political regimes and interventions that plagued the region. Since the recent cycle of democratization, the processes of academic institutionalization and professionalization of sociology have been reconverting its legacy and practice in the face of growing internal and external social demands.

A locally rooted profession that experienced rapid internationalization

The formation of sociological communities took place along a double axis: local rooting of the production of sociological knowledge, in dialogue with Latin American and international academic spaces. The early insertion of sociology into circuits of internationalization was evident via simultaneous entry into the International Sociological Association (ISA) and the Latin American Sociological Association (ALAS) in 1950. This was followed by the Latin American Association of Rural Sociology in 1969 and the Latin American Association of Labor Studies in 1993; and, with a sub-regional profile, the Central American Sociological Association in 1974. At the same time, the internationalization of sociology was in permanent dialogue with other social sciences, expressed via active participation in regional networks such as ECLAC (1948), FLACSO (1957) and CLACSO (1967).

There were multiple indicators of the progressive formation of academic communities of sociology (research centers, universities, careers, specialized publications, etc.). Still, at the same time, this was made possible and enhanced by a community of actors, professors, intellectuals and sociology professionals who exercised their profession in various fields, built networks and associations, and gathered at public events to present themselves as a category and professional group to society.

A ritual sense of collective belonging to the profession is the celebration of an official commemorative date of the sociologist. In Chile, this is the national day of the sociologist on November 24, commemorating the creation of the College of Sociologists in 1982. In Colombia, December 10 recalls the creation of the first chair of sociology in the country in 1882. In Panama, the date celebrated is December 12, to honor the sociologist and writer Raúl Leis Romero, while in Peru it is December 9, recalling the first chair of sociology at the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos in 1896. Finally, in Venezuela, February 11 recalls the founding of the first College of Sociologists and Anthropologists.

Sociological associations: main objectives and development

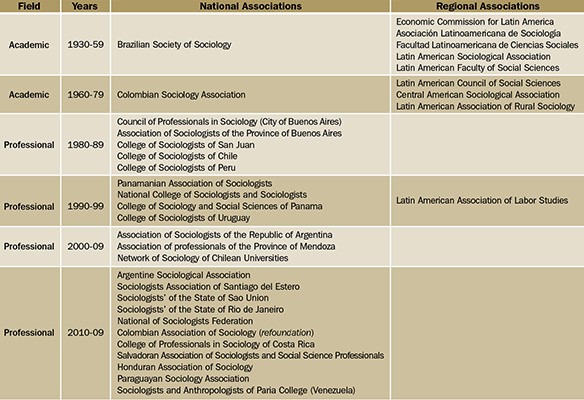

In order to present a general overview, a classification of sociological associations in Latin America has been drawn up according to: a) priority objective of action, oriented to the academic or professional field, b) age and longevity, and c) territorial scope.

Combined analysis of the nature of the association (academic or professional) and time variables (age and longevity) reveals interesting empirical observations. The development of the associations over the long term shows a slow and uneven implementation, although with a progressive growth in the number of associations and of countries with associations.

Comparative longitudinal analysis made it possible to establish three historical periods with specific profiles, in line with the analysis presented in the previous sections. There was a foundational period of Latin American sociology between the 1930s and 1970s, characterized by the development of associations from the academic field, networks and expressions at national and regional level. This was followed by a cycle of expansion of associations with a more professional profile, in the 1980s and 1990s, during which there was a shift from academia to extra-university fields in the practice of the sociological profession. This period was accompanied by growth in the number of graduates and non-academic spheres of practice of the profession. Finally, we can identify a period that spans the first two decades of the twenty-first century, characterized by the diversification and institutional consolidation of the training of sociologists (undergraduate and specialized postgraduate) and institutions and associations becoming rooted at the territorial level. This period saw progressive and parallel growth of academic and professional associations in many countries.

Networks, international solidarity and the emergence of colleges and professional associations

Diverse associations contributed to the collective production of multiple forms of solidarity and the development of networks. This provided a sense of belonging and endogenous identity for the professional category in different ways, such as the establishment of membership in a group or the organization of social meetings at sociology events and congresses, among others. There were also mobilizations, advocacy and public commitment to social causes and the defense of vulnerable social groups together with practices oriented towards international solidarity, especially in Latin American networks.

The emergence of colleges and associations with a professional or guild profile aimed at defending, promoting and strengthening the professional field of sociology has been a more recent development. These are linked to the public legitimization of sociological knowledge and its profession, as well as to the advancement of legal and normative regulations in the practice of the profession. Such regulations are heterogeneous and partial, from non-existent specific legislation for the profession – in most cases – to strictly regulated professional colleges, both at national and sub-national levels, in several countries (such as Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Peru and Uruguay).

Current risks and challenges

The development of academia, associations and the craft of sociology has by no means been the result of a linear evolution or progress but has faced multiple obstacles and challenges. On the one hand, conservative sectors in Latin America distrust the social sciences and sociology in particular, with sociologists being perceived as a threat to the social order. On the other hand, new social demands for scientific and professional knowledge can result in risks that undermine substantial aspects of the practice of the sociological profession.

Added to this are the transformations in the world of professions. These include the multiplication and relative devaluation of university credentials and degrees and the processes of flexibilization and precariousness of professional labor markets. Moreover, the irruption of teleworking, which has consequences in terms of the distribution of care and gender inequalities, has been particularly visible in the social sciences. Due to the growing productivity demands of cognitive capitalism, there are also risks of substituting a critical profile and analytical reflection by an overvaluation of soft skills and the technical management of data from the market.

The challenge for the sociological profession is to adapt to the demands of the new dynamics of social knowledge without losing its sense of critique and social commitment. This means taking up the historical legacy of Latin American sociology’s activism, of commitment to profound changes in the social order, and to the culture of anti-authoritarian resistance. In an epochal change, it requires the role of intellectual critique of power structures and public denunciation of the social inequalities that pervade the region. Furthermore, it is necessary to recover the sociological critical look at society to make problems and social actors that have been marginalized visible, to uncover the social mechanisms that make the reproduction of institutions of power and inequalities possible, and to question, through critical reflection, the simplification and naturalization of common sense in the explanation of recurrent social issues on the public agenda (such as violence and its uses).

In short, it is necessary to resort to the “sociological imagination” as an essential professional resource. Beyond legacies, conditioning, and challenges, its associations and its craft are probably sociology’s greatest strengths as society changes.

Miguel Serna, Universidad de la República, Uruguay <miguel.serna@cienciassociales.edu.uy>

* For the review of data sources, I would like to thank colleagues from the ALAS network of sociological associations and professional associations, particularly Eduardo Arroyo (Peru), Ana Silvia Monzón (Guatemala), Flavia Lessa de Barros (Brazil), Alejandro Terriles (Argentina), Raúl González Salazar (Venezuela), Briseida Barrantes Serrano (Panama), Carmen Camacho Rodríguez (Costa Rica), and Mónica Vargas (Chile).