From Chiapas: Facing an Unequal World

May 17, 2014

The year 2014 marks the twentieth anniversary of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Canada, Mexico, and the USA. NAFTA was the first such agreement between countries at different levels of development and thus became the basic reference for subsequent treaties and the current negotiations toward the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) of twenty Pacific Rim countries and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the European Union and the USA. Conceived during the first Bush administration and implemented under Clinton, it provided a model for bringing down tariffs to benefit export-oriented corporations while undermining workers’ interests and environmental concerns.

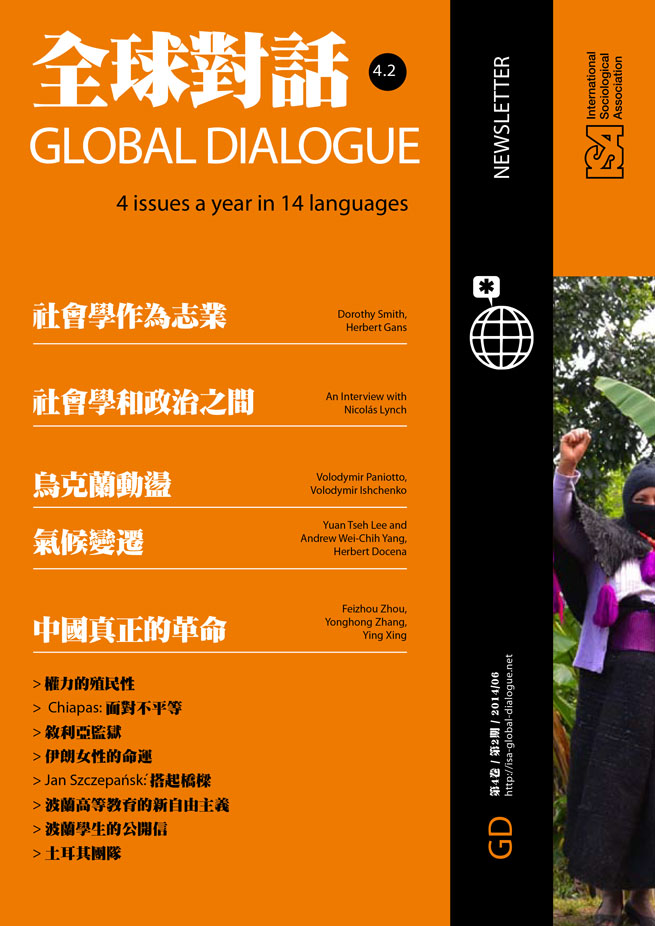

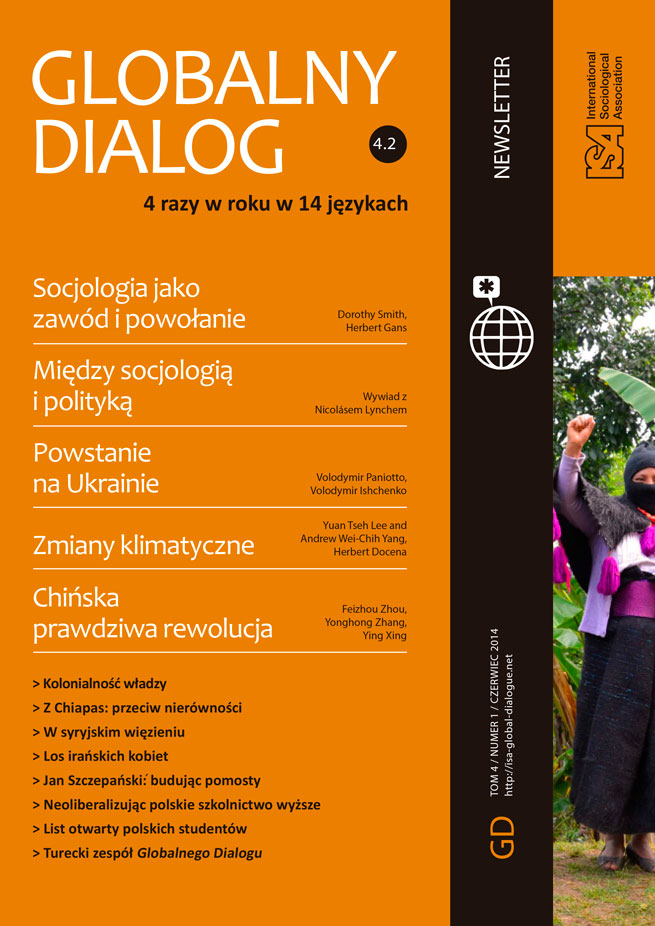

2014 also marks the twentieth anniversary of the indigenous uprising in Chiapas. When the Zapatistas rose up in arms on the day NAFTA took effect, they connected local struggles for land, civil rights, and a dignified livelihood with broader struggles for democracy and social justice on a global level. Over the years, the Zapatistas inspired a critical discourse and the formation of transnational activist networks that, in turn, organized the large demonstrations in Seattle, Prague, Genoa and at other summits where global elites plotted the neoliberal restructuring of the world economy.

Although the mass media spotlight has turned away from Chiapas, it would be a mistake to think the Zapatista movement has withered away. The rebellion continues, albeit in changing ways. The insurgent Mayan communities have established their own autonomous municipalities where they experiment with grassroots forms of self-governance. The rotating delegates of the local and regional boards are bound by the principle of “mandar-obedeciendo,” i.e. to govern by obeying. In December 2012, the Zapatistas displayed their strength by mobilizing tens of thousands in a silent march through San Cristobal de las Casas, the major city in the highlands.

This past summer, the Zapatistas started their latest initiative by inviting visitors to their communities to learn what they mean by freedom. Their “Little Schools” (escuelitas) turned the tables: The world was invited not to teach the indigenous about development but rather the other way around, to see, listen, and learn from their experience, how they carve out a social alternative, how they create participatory structures of autonomous self-governance. The escuelitas were not for big speeches on high podiums but for first-hand learning from their lived practices of daily resistance.

More than twelve hundred people of all ages traveled from across Mexico and countries around the world, including activists, artists, intellectuals, farm workers, musicians, poets, street vendors, students, and sympathizers from diverse walks of life. There were no tuition charges. Room and board were free, even transport. Attendants were only asked to pay one hundred pesos (roughly ten dollars) for printed study materials, while a sealed jar provided opportunity for anonymous donations. The Zapatistas explained that big donors should not feel too full of themselves while those without money should not be embarrassed.

Common meetings provided opportunities for questions and answers about the Zapatistas’ visions and guiding principles but the main part of learning took place in the communities who had prepared the visits over several months. Each student was provided with a Votán, or guardian and tutor, as an embodiment of the community. “There is not one teacher,” explained Subcomandante Marcos, the Zapatistas’ spokesperson, “but rather a collective that teaches, that shows, that forms, and in it and through it, the person learns, and thus also teaches.”

The story of one of the guardians, a young Tzotzil, stands for the experience of many in his generation. Having obtained two years of secondary schooling, he was now himself teaching in the community’s own elementary school. He had experienced a different way of life in Cancún. Allured by the prospect of earning money, he went to the big city and got jobs in construction, restaurants, and hotels. He described his fascination with the splendor of the city’s shiny-white mansions and resort complexes but also how he witnessed the abject poverty of the majority population just a few blocks away from the coastal strip and the wealthy neighborhoods. He endured for over a year this way of life in the cash economy, being bossed around, often even being cheated of tips, sometimes of wages too. In the end, he had enough and returned to his community. He preferred dignity over discipline, community over competition.

Twenty years after the uprising, an autonomous school system is now in place, in which the Zapatista communities define the curriculum according to their needs, values, and priorities. They had started by building a secondary school in one of the regional centers, where students would typically stay for two-week periods, due to the often-lengthy commutes. Elementary schools were established at the local community level, taught by those with at least some schooling. The Zapatistas consider this system far superior to the official schools run by the government with teachers who often do not speak the local language and who despise being sent to remote locations away from family and urban amenities. The Zapatista teachers prefer to be called promoters of education because they reject the conventional top-down approach of instruction in favor of a more cooperative way of learning together. Their teaching is unsalaried. The community provides accommodation, food, time off from communal works, and a small allowance for clothing.

Sharing life in a community included working in the fields, planting vegetables, picking fruits, swimming and washing clothes, preparing food, eating together, singing songs and telling stories. If classified by material measures, the living standard of the community where I stayed in the summer was quite poor. The adobe huts were simple and had only barren floors. There were neither any modern appliances nor access to the electric grid. On the other hand, there were many advantages too. The setting was tranquil, well away from noisy highways or polluting industries. A nearby stream provided fresh running water. The diet consisted mainly of corn tortilla, rice, beans, vegetables, occasionally an egg, but usually neither meat nor commercial soda. Largely locally produced, it was fresh, organic, and flavorful. Perhaps most important, the community showed a strong sense of dignity and took pride in their autonomy.

Corn is the main pillar of Mayan subsistence farming. NAFTA exposed Mexican peasants to competition from the US where corn is produced at industrial scales in large monocultures with heavy government subsidies. This brought pressure to abandon the land and seek jobs in cities or abroad. The Zapatistas continue to grow corn for their own consumption in traditional ways on their milpas, small fields on often steep slopes, shared with other plants such as edible weeds, squash, and especially beans, which use the corn stalks after the corn harvest. The Zapatistas oppose the GMO seeds propagated by corporate giants such as Monsanto. They contrast the genetic diversity that evolved during almost 9,000 years of Mesoamerican cultivation with the narrowness of the few in-bred lines of US agribusiness that rely on pesticides.

A major transformation occurred in gender relations. The Revolutionary Women’s Law promoted gender equality. As this constituted a break with deeply rooted patriarchy, some communities adopted it faster than others. For example, when faced with the high expenses for transportation and food, families living far from the secondary school may send only their son but not their daughter, thus reproducing imbalances. However, there are many signs that the younger generation is embracing gender equality more readily. For example, young men no longer consider the washing of clothes to be a woman’s task but can be seen doing laundry themselves. Likewise, an increasing number of women serve as promoters of education and health and on the boards of self-governance.

The Mexican government’s strategic response to the Zapatistas has changed over time. It had halted its early military campaigns after massive protests across Mexico and abroad. More recently, the government sponsored the construction of a Rural Sustainable City and an assembly plant right next to Zapatista strongholds. Yet, the promised jobs that could have lured peasants into abandoning their land quickly disappeared when the subsidies ran out, and the brand-new, brightly painted houses are mostly vacant, as they were deemed deficient in construction. While there are currently no army incursions into the communities, there are worries over low-altitude overflights by military airplanes. The Zapatistas consider the current Mexican President as having come to power only thanks to an unfair election system and massive media bias. The political system is in the Zapatistas’ view so corrupted that they refuse to cooperate with any of the political parties.

The Zapatistas’ resistance is simultaneously political, economic, social, and cultural. It is about making self-governance and subsistence work, creating a social model with inherent appeal. Their answer to the question of social justice starts with freedom. They do not ask for permission, but they do things. Structural adjustment policies have increased urban slums worldwide; it is time to recognize development innovation from the ground up. A sociology with global aspirations and attuned to the problems of inequality can benefit from paying close attention to the struggles at the grassroots in the peripheries of the Global South.

Markus S. Schulz, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA, member of the Program Committee of the 2014 ISA World Congress, and President of the ISA Research Committee on Futures Research (RC07)