Read more about From Latin America

From Chiapas: Facing an Unequal World

by Markus S. Schulz

The Coloniality of Power: A Perspective from Peru

by César Germana

May 17, 2014

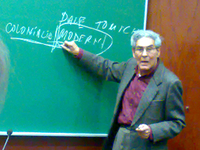

Nicolás Lynch is a Professor of Sociology at the National University of San Marcos in Lima, Peru. He has been President of the Peruvian College of Sociologists (1998-2000) as well as Minister of Education of Peru (2001-2002), Advisor to the President of the Republic (2002) and Peruvian Ambassador to Argentina (2011-2012). With a PhD in Sociology from the New School for Social Research, New York, and an MA in Social Sciences from the Latin American School of Social Sciences, Mexico, he has been visiting professor at several US universities. He has published many academic articles and several books, including Los jóvenes rojos de San Marcos [The Red Youth of San Marcos], La transición conservadora [The Conservative Transition], Una tragedia sin héroes [A Tragedy without Heroes], El pensamiento arcaico en la educación peruana [Archaic Thinking in Peruvian Education], Los últimos de la clase [The Worst of Education], ¿Qué es ser de izquierda? [What does it mean to be a Leftist?] and El argumento democrático sobre América Latina [The democratic argument about Latin America]. He has been a political columnist for fourteen years at the Lima newspaper La República and is the editor of the blog of political analysis, Otra Mirada [Another View].

MB: For a sociologist your career is very unusual, in and out of politics. In fact, perhaps we should start there: are you a politician or a sociologist?

NL: I am a sociologist, not only by training but also because I love sociology. I am a sociologist who likes politics. But the fact is that I was born in a country where social change is a matter of life and death so I have been involved in political activities since I was a teenager.

MB: That’s interesting. Max Weber was an aspiring politician, but he always saw sociology as science, separate from politics, that’s obviously not the case for you. Am I correct?

NL: For me sociology is a science, but a social science, so we are social actors who are also part of the world we study. Sociologists like Alain Touraine, who is very influential in Latin America, underline this “sociology of the actor” and I think he was right about that. Since the beginning, my sociological research has been linked to my political life. Most of my books reflect that.

MB: Now let’s turn to your latest engagement with politics. You were Peru’s ambassador to Argentina. How did that happen?

NL: I became part of President Humala’s electoral team in late 2009, invited by some friends that had already participated with him in the 2006 election, when he came in second after a great campaign. I had resisted the temptation to join someone who portrayed himself as a leftist nationalist but, at the same time, was also a retired army officer who had fought the “dirty war” against the Sendero Luminoso [Shining Path]. But the poor results of the socialist left in that same election of 2006 led me and other friends to join forces with Humala. Seeing things from today I think my original instinct was right, but I also believe we were deceived from the beginning. All Humala and his wife wanted was power for their own good.

MB: So in return for your support in his election campaign, President Humala offered you the opportunity to be Ambassador to Argentina. What did he want you to do in Buenos Aires?

NL: He sent me to Argentina to accomplish several political goals. Peru did not have good relations with Argentina because the government before Humala (The Apra party lead by Alan García) disliked the Argentinian government because of its progressive political positions. The President gave me the task of improving that relationship, which is what I did. This was especially important with regard to South American integration and UNASUR (the Union of South American Nations). Humala told me to put Peru on the map of integration and that was the focus of my work.

MB: What were the challenges and satisfactions of this job?

NL: First, the life in Buenos Aires, especially the cultural and intellectual life, is probably the richest in Latin America. Also Argentina was going through important processes of social and political change which was especially interesting in the light of its strong political traditions. The Argentinians have made incredible advances in terms of the redistribution of wealth, in terms of human rights and in terms of political independence from world powers. As compared to other Latin American countries, Argentina has the highest levels of employment in formal jobs with labor rights. Unusual for Latin America, they have jailed around 200 military personnel involved in the repression of the 1970s. As a result of all these changes Argentinians have developed a strong sense of citizenship, to levels unknown elsewhere in the region.

MB: But it all came to a very sudden end, right? You suddenly lost your job?

NL: Well, the Humala government, elected on a leftist platform to which I was a contributor, turned to the right. Of course, this did not happen overnight, it was a long process. First, he expelled the progressive wing of the cabinet, then he broke up with the leftist congressmen and, finally, with anyone who was connected to his progressive origins. Instead of resisting the pressure of the Peruvian right and the American government, he decided to give up his goals of transformation and to continue the neoliberal agenda of the previous twenty years. As the Humala government turned to the right, so the President’s new allies wanted to get rid of me, and they prepared a trap. Maybe my mistake was not to resign first. but it is very difficult to exercise good judgment in these complicated political situations.

MB: What was the trap they set for you?

NL: In late January 2012, while in the Peruvian Embassy in Buenos Aires, I received a letter from a group of Peruvians who were campaigning for the legalization of Movadef, a political front for the terrorist organization, the Shining Path that was seeking amnesty for their leaders who are in jail for their crimes. Ten months later, in early November, on the basis of this letter, a right-wing Peruvian newspaper denounced me as a Movadef sympathizer, demanding that I be fired from my position. The government neither defended me nor ordered an investigation. They were so scared of the right wing offensive that they asked for my resignation. Of course, I have never had any relationship with Movadef or the Shining Path. Indeed, in 1982 the Shining Path sent me a letter with a death threat and, at that time, they assassinated several of my friends. They are a terrorist group that never undertakes any self-criticism of their actions. Irrespective of the falsity of their accusations, right-wing groups inside and outside the government were strong enough to ensure my exit from government.

MB: Well, I can see how precarious politics can be in Peru. But this was not the first time you were in government. You were Minister of Education in 2001 in the Toledo Government that sought to restore democracy to Peru. Tell me more about that.

NL: This was the result of the struggle against the Fujimori’s dictatorship. I had been a member of the Foro Democrático, a civic organization, which formed part of a coalition to overthrow this regime. Toledo, a centrist of liberal origin, at the time represented a new beginning for Peruvian democracy and he formed a first cabinet with people from different backgrounds.

My purpose was to start educational reforms that would improve our system of education which was one of the worst in the region. It operated with a very low budget and its results were of very low quality. I had to deal with two enemies: the World Bank and a Maoist trade union of teachers. The first, as always, wanted to privatize everything and the second wanted to retain job security at any price, blocking any evaluation of the work of its members. We did succeed in putting reform on the political agenda, but Toledo was unable to withstand the pressure from these people and so he fired me and my team.

MB: I see this politics is a treacherous business, especially as you never abandoned your leftist views! So in this context does sociology give you something to fall back on? Does it gives you solace in the face of such uncertainty? But does it also contribute something to your politics? Is sociology politics by other means?

NL: It’s not just solace. Sociology helped me understand Peruvian society and the place Peru has in the region and in the world. Regarding education, for example, sociology helped me understand that the problems of Peruvian education were ideological and political, not the technical ones that the international agencies wanted us to believe. Sociology gave me the tools to understand that educational quality is not just a matter of good grades but calls for a collective self-understanding of your place in the world, your sense of belonging.

I have never left academia. For 34 years I have been teaching sociology at the University of San Marcos, which is the oldest and most famous university in Peru. During these years I have participated in at least nine big research projects. They have resulted in quite a few books, of course some more important than others, some more political and some more sociological.

MB: Very few of your books have been translated so perhaps you can give us a sense of these research projects or, at least, one or two that you consider to be most important, showing the connection to politics.

NL: Well, their absence in English has to do with my complicated relationship with the American academy. As an example, take my work on populism. I wrote a piece about populism in Latin America in the late 90s, trying to explain why populist neoliberalism did not exist, that it was a contradiction in terms. I wrote that historically populism had been good for the region and for democracy. After being published in Spanish I sent it to an important “comparative” journal in the US. Months later I received a long comment telling me I didn’t know what populism was about. OK, I said they think differently. But the problem was that in the same journal they published an article criticizing mine, citing the Spanish version. So, my article was not good enough to be published but good enough to be criticized! Many times I have received the same argument: if you disagree you don’t know what you are talking about.

My latest book is about the different approaches to Latin American democracy in theory and in practice. I wrote it trying to explain how the new progressive governments in the region – from Hugo Chávez, to Lula, Correa, Evo Morales and the Kirchners – were trying to develop a different kind of democracy, promoting redistribution, social justice and participation. The goal of the book is to present a different view on democratic regimes from the dominant one, which came from the discourse on transitions and consolidations.

MB: And today are there ways in which your sociology enters political controversy?

NL: Oh yes! For example, in the last few months we have had a debate in Peru about the middle class. The neoliberals and the people who are in the business of polling have been claiming that 70% of Peruvians are middle-class, based on a strange income distribution table. So together with some friends we’ve been writing about social structure, social class, and class struggle – once again after so many years – to show how these pundits are misguided in theory and in practice, and how sociology has a more precise and sophisticated understanding of these issues.

MB: You got your PhD in sociology in the United States and you have returned there periodically. In fact that’s where we first met at the University of Wisconsin. What’s a Peruvian leftist doing in the US?

NL: I got my MA in Mexico and I have been all over Latin America and Europe for different kinds of academic engagements. In the US, as in any country, there is a plurality of possible places to study. I ended up doing my PhD at the New School for Social Research in the 80s, a very good and progressive university. I have been a visiting scholar in other places too, such as Madison, Wisconsin. I think we must push for dialogue and contact across the Americas. It does not matter if we disagree but we have to understand each other.

MB: I’m wondering whether there is something in your biography, perhaps your early education or your family background that has driven you in two directions – politics and sociology – simultaneously?

NL: Well, for many people I do not fit into the Peruvian political scene. I am of upper middle class origin, I do not have any indigenous ancestry, and I have had (or so I think) a good education. Maybe it is the terrible reality of persistent social inequality in Peru that has led me to be dedicated to this double life of interconnected threads. But I have been happy doing both politics and sociology. As I have said they re-enforce each other. I have no regrets.

MB: Now that you are out of government how are you keeping yourself busy? Are you still engaged in politics? Are you writing more?

NL: Yes, I am in politics. I am a member of a leftist coalition, which has a base in almost every region of Peru. We have good prospects for the next regional elections in 2014. I also have a web site which I organize with a group of friends – a platform for political analysis through the Internet. We send a page of news analysis to almost 15,000 email addresses every day, we have a radio program, and we also write papers analyzing public policy. As a said I also continue to give classes at the University of San Marcos and I am finishing a book, which is a long political essay about the foundations and future of the Peruvian republic.

MB: I think Max Weber would be very envious of you – at home in both sociology and in politics, weaving the two together but still never mistaking the one for the other! Thank you very much for this wonderful interview.

Michael Burawoy, Editor of Global Dialogue

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: