With China’s changing position in global capitalism and the reconfiguration of its social structures, an increasing number of urban middle- and upper-class families are moving to a select few countries across the globe. Surveys indicate that this “exodus of the wealthy” is motivated by postmaterialist concerns rather than by aspirations for further accumulation. They constitute an emerging market for the “golden visa” programs launched by countries to attract foreign capital by selling residency and citizenship. In recent years many of these Chinese “golden visa migrants” have started to favor East and Central European countries where governments have been eager to welcome them with cheaper immigration schemes.

Hungary’s “golden visa” program

Hungary’s “golden visa” program was one of the most welcoming offers to cater to this newly emerging market: between 2013 and 2017, when the program was in force, Hungary managed to provide the second least expensive scheme within the European Union, outcompeting all of its counterparts in terms of the simplicity and speediness of its procedure. This, and the lack of any further requirements beyond the purchase of state bonds with five-year maturity for around 250,000 Euro (later 300,000 Euro) plus commission fees allowed over 19,000 applicants − 81% of them from China − to receive residence permits. Despite having been designed specifically for “migration without settling,” however, the program, instead of luring businessmen interested in increased mobility within the EU rather than actual immigration, seemed to mostly attract families who effectively seized this opportunity to move abroad. They used investment as an instrument for pursuing particularly non-economic ends: a wholesome environment for raising well-rounded children.

Chinese “golden visa” migrants in Hungary are middle-class families from metropolitan China (mainly from Beijing, Shanghai, or Guangzhou) who continue to rely on incomes or remittances from China. Unlike the small-scale traders, mostly from southeastern China, who first came to Hungary in the early 1990s mostly for the purposes of economic accumulation, these families migrate to Hungary to pursue a relaxed lifestyle in an environmentally green, culturally rich, and racially white urban setting that is imagined as the authentic “Europe” − at a discounted price in the bargain.

These families’ decision to leave China and their choice of Hungary is anchored in the particular historical, social, economic, and political construction of childhood in reform-era China under the “one-child policy.” When the government introduced its family planning program in the late 1970s, one rationale was that the reduction of the population’s quantity would improve its “quality.” Quality thus became a fixation for middle-class parents, who were charged with cultivating their only child’s quality to the greatest possible extent. According to official discourse, an individual’s bodily, moral, and educational quality is not only a matter of individual effort, but also a consequence of environmental influences. However, middle-class parents’ expectations for such an environment outgrew what metropolitan China could meet.

European home at a discount

In this light, Hungary is considered by middle-class Chinese migrants to be an ideal destination, where the physical, social, and educational environment is satisfactory and the cost of living is affordable. For many of the Chinese golden visa migrants the goal is to find a well-located, suitable real estate, which, besides being a good investment, can also become a home for the family. The phenomenon of an ideal home is attached to the sense of “finality and settling down,” and tied to the notion of home ownership. The possibility of owning an inheritable home gives Chinese migrants a chance to establish a better quality life for lower capital expenditure in Hungary − in the vast majority of cases in the capital city, Budapest − than in one of the Chinese megacities, or in any of the global or gateway cities of contemporary capitalism.

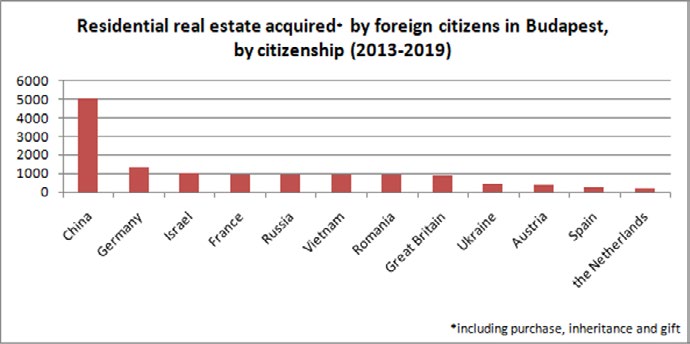

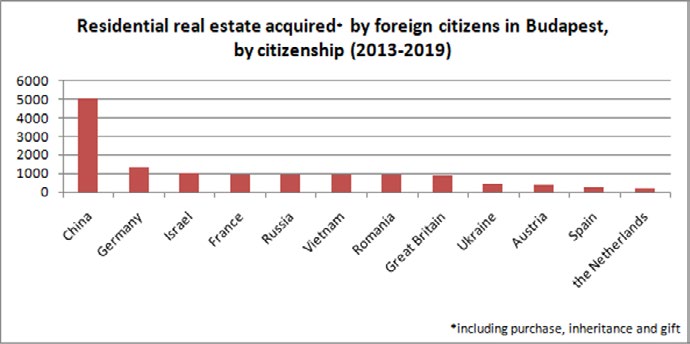

Since the launch of the Hungarian golden visa program there had been a significant increase in Budapest housing property acquisitions by foreigners until last year; despite the general boom of the housing market, Chinese comprised the largest group of foreign individual investors.

Among Chinese residents, it was not only golden visa immigrants who were attracted to Budapest real estate. A number of small-scale traders turned to housing investments, too. Our research suggests, however, that while the city center was popular with both groups, small-scale traders were more prone to purchase properties close to Chinese wholesale and retail markets, or in more affordable areas of the Pest-side suburbia. Golden visa migrants tended to show more interest in new housing developments, in the hilly and green areas of the costly Buda side, and in detached houses of the Budapest metropolitan area.

Even if a number of golden visa migrants managed to purchase property both for investment purposes and for settling down, when it came to the choice of home, they mostly looked for apartments in neighborhoods where the quality of schools and housing was reputed to be high. The abstract ideas of quality have been mapped onto space and assessed as an ideal intersection of a neighborhood’s and school’s racial (referring here to the presence of Roma or immigrant children) and class constitution, taking shape in a form of selective cosmopolitanism. Attracted to Western lifestyles but alarmed by the presence of Muslims and/or Blacks, many Chinese newcomers have leaned on the current Hungarian government’s highly anti-immigrant right-wing populism − despite being migrants themselves. Many newcomers emphasized their perception about Hungary as being far more welcoming towards them than Western European countries, and experiencing close-to-no discrimination. Paradoxically, the same interlocutors praised the government’s selective immigration policy that resulted in the settlement of relatively few refugees, and Muslim and/or African immigrants as contributing to their sense of security.

The provision of Hungarian residency and citizenship status is used strategically by the national government as a policy tool to access economic resources outside of Western Europe − either through the golden visa program, or through special channels as part of interstate diplomacy. This both enforces the economic interests of the ruling political elite and helps to gain some political and economic leverage at the level of the EU. As citizens of a rising global power outside of the transatlantic power bloc, Chinese golden visa migrants could become beneficiaries of this process; ironically, they could attain a feeling of being at home in Budapest and a sense of belonging to Europe under these controversial political and economic circumstances.

Fanni Beck, Central European University, Hungary <beck_fanni@phd.ceu.edu>

Eszter Knyihár, Eötvös Lorand University, Hungary <nyihar.eszter0302@gmail.com>

Linda Szabó, Periféria Policy and Research Center, Hungary<szabo.linda@periferiakozpont.hu>