Why Do People Vote For Right-Wing Parties?

December 04, 2018

As Arlie Hochschild explained in Global Dialogue in 2016, sociologists need to search for answers to the question posed in this article’s title not only in economic processes and emergent social sentiments, but also in the biographies of the supporters of these parties. A similar intuition informed our research team (consisting – besides of authors of the text – of Prof. Maciej Gdula as a principal investigator, and Stanisław Chankowski, Maja Głowacka, Zofia Sikorska, and Mikołaj Syska) who explored the reasons for the growing support for Law and Justice (PiS), the ruling party in Poland since 2015. Law and Justice is considered a socially conservative party: conservative in the sense of values and etatist on the economic dimension. Even though this Eurosceptic and nationalist government has faced a lot of criticism both from the European Union and the more liberal parts of Polish society, its support has been steadily growing: it hit 50% in polls conducted at the end of 2017.

Introducing our study

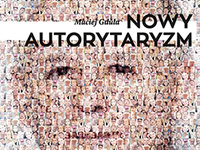

Our study was conducted in a county town in central Poland which we dubbed “Miastko” (“small town” in Polish). The ruling party received almost 50% of the votes in Miastko in 2015, compared to 37.6% nationwide. Our report was published as “Good change in Miastko: New authoritarianism in Polish politics from the perspective of a small town.” PiS politicians have used the notion of “good change” since the beginning of the 2015 presidential campaign.

To explore the political convictions of PiS supporters, we conducted two interviews with each of the 30 respondents – inhabitants of Miastko: the first interview was a biographical one, and the second one concerned their views on issues such as abortion or welfare state policies. Our methodology drew on Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of class distinction and its Polish adaptation by Maciej Gdula and Przemysław Sadura. We divided our respondents into two groups: the working class and the middle class. It is important to note that we did not conduct interviews with the so-called “losers of transformations,” a term denoting people who had fared poorly under the capitalistic changes after 1989.

Two highly contested topics: abortion and refugees

Working-class interviewees generally opposed a total ban on abortion. Older working-class women favored liberalization of the existing anti-abortion law. Middle-class women usually argued for the need for freedom of choice for women and stressed the burdens of bringing up an ill child. Despite some of our interviewees’ significant openness to a possible liberalization of anti-abortion regulations, there appeared also a strong voice against abortion in general.

Most of our interviewees were against accepting refugees in Poland. Working-class interviewees argued that the refugees would not want to work and would expect social benefits. They highlighted the danger they posed to the Polish system of social care and the injustice resulting from benefits they may obtain. They linked the situation of refugees with war and usually admitted that they should receive support, but were opposed to helping them on Polish territory. Only two argued that accepting refugees into Polish society would not harm anybody – because of the small numbers the former government had proposed accepting.

Middle-class interviewees claimed more often that the incomers represented a different culture and were unwilling to accept the rules of Polish and European culture. The references to solidarity with those escaping war, and to the commonality of their experience of war and political instability with Polish society, appeared extremely rarely. According to middle-class interviewees, refugees should stay “where they belong, where they have their own place.” For some, the idea of Europe was one defined by exclusion; protecting the “purity” of Europe required that refugees, identified only with their religiosity and ethnic background, should be left outside. The disposition to order and clear boundaries appears in a solution proposed by one of our middle-class female interviewees: if the refugees need to be in Poland, they should be separated from Polish society.

Destruction of institutions of the democratic rule of law

In December 2015, the government started to obstruct the work of the Constitutional Tribunal which is mandated to judge whether a law is in accordance with the Polish constitution. The previous government had elected five judges to the Constitutional Tribunal in September 2015, just one month before the legislative election. The then-parliamentary majority, an alliance of the conservative-liberal Civic Platform and the Peasants’ Party, had the right to elect three judges, but elected five. Despite the fact that the Tribunal maintained the election of three (legally elected) judges and invalidated that of two (illegally elected) judges, the new PiS-dominated parliament nominated five new judges and stopped the publication of the Tribunal’s decisions. The swearing-in of the newly elected judges by President Andrzej Duda led not only to a constitutional crisis, but to street demonstrations in Warsaw and other major Polish cities. The answer to the question whether the government’s measures concerning the Constitutional Tribunal were legitimate was not split across class lines, but across partisan lines: PiS supporters were in favor of its actions, claiming that it restored “plurality” to an allegedly Civic Platform-dominated Tribunal; for its opponents these measures were an assault on democracy and a successful attempt to suspend any constitutional control over the government.

PiS social policy: the “Family 500+” program

The “Family 500+” program was introduced in April 2016 as the flagship of the PiS government’s social policy. It is certainly one of its most important political measures. The program is a universal child benefit program; each family receives 500 zlotys (about 120 euros) for the second and third child (poor families can receive the money also for the first child). Its implementation marks a significant change in post-communist Poland: it is the first time since 1989 that the Polish state has implemented a large-scale redistribution effort benefitting both the middle and the working class.

Most participants supported the implementation of child benefits, the only exceptions being some middle-class adherents of the liberal opposition who regarded it as a form of “buying votes.” The benefits found favor with the majority of the middle-class interviewees who considered their introduction a symbol of the country’s new strength. Paying out child benefits was not seen as an extravagance, but rather as a “normal” measure typical of well-developed countries of the West, and a sign that Poland was joining them. Working-class participants were also in favor of the child benefits, although a significant part of them also expressed support for the proposition that local authorities should control the benefit expenditure of some recipients.

The causes for support of the PiS are multilayered

Law and Justice represents a new model of ruling by bringing their redistributive program to life. Our research found that supporters of PiS are far more differentiated than is assumed by public opinion. In this article we try to explore what these social differences are and to what factors we can attribute the rise of right-wing parties.

Our research showed that it is not only financial support for the poor that has triggered support for the PiS. Instead, it is successful because its actions appeal to the various needs and values of all classes. PiS politicians respond to the working class’ needs for dignity and recognition by criticizing the limitless consumption of the former “elites” at the public expense. They also speak to the dispositions of the middle class in their desire for sovereignty and order. Our study revealed a very interesting pattern: political opinions and declarations do not always overlap with the personal experience of interviewees.

At the same time, PiS has begun to destroy democratic institutions (such as the Constitutional Tribunal), all in the name of democracy and “good change.” The research unveiled that adherents of PiS consider themselves “democrats,” but reject its liberal form which is essentially based on self-limiting. Maciej Gdula refers to this new phenomenon by the term “new authoritarianism.” According to Gdula, we now observe a new phenomenon – this “new authoritarianism” characterized by radical change of the public sphere (dominated by the Internet, rather than by newspapers as in the past) and a specific relation between the voter and the ruling party’s leader.

The results of our research confirmed that prevailing explanations of the right-wing parties’ success had been exhausted. The findings have gained enormous public attention and triggered a wide public debate involving both left- and right-wing intellectuals who engaged in discussing the divisions in Polish society.

Katarzyna Dębska, University of Warsaw, Poland <k.debska@is.uw.edu.pl>

Sara Herczyńska, University of Warsaw, Poland <sara.herczynska@gmail.com>

Justyna Kościńska, University of Warsaw, Poland <j.koscinska@is.uw.edu.pl>

Kamil Trepka, University of Warsaw, Poland <k.trepka@is.uw.edu.pl>