Who’s to Blame? Stormy Times in Climate Change Negotiations

November 19, 2011

This December, thousands of officials, activists, lobbyists, and maybe even some superstars will fly to Durban for the 17th conference of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Next June, many will again fly to Rio to mark two decades since the signing of the UNFCCC and other environmental agreements. Twenty years have now passed since what many now agree were the most complex – and perhaps most consequential – intergovernmental negotiations in history, but what has been achieved?

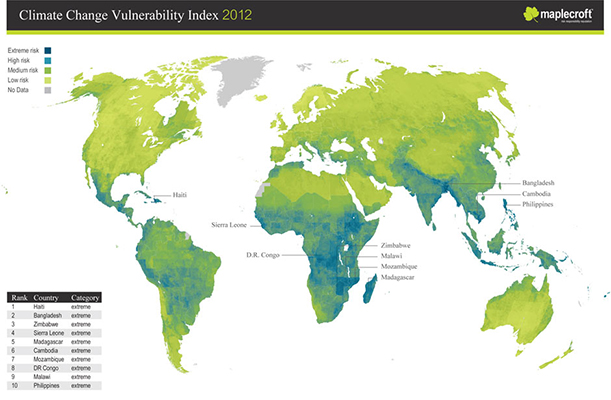

As I write, in Bulacan, Philippines, hundreds are spending another stormy night on their rooftops, hungry and waiting for rescue because of rising floodwaters unleashed by the latest super-typhoon; they wait because in a village of thousands, there are only two rescue boats to go from house to house. This, just a few days after the country paused to remember the anniversary of the worst typhoon in recent memory – and a day before yet another typhoon is set to hit shore.

Two decades since governments first agreed to reduce emissions, storms are getting stronger and more frequent while droughts are getting more severe – just as climate science predicts. According to a report released last May by the International Energy Agency, carbon emissions last year have actually been the highest in history. Why, despite accords, are emissions that are blamed for what the philosopher Peter Singer calls “bizarre new ways of killing” still rising and rising?

I went to Bonn to observe the climate negotiations last June and was struck by what was being debated: a variant of ‘pledge-and-review,’ a proposal in which each country would essentially be left to itself to decide how it wants to act. No binding targets, no promises. In another hall, Bolivia was calling for a global tax to fund efforts to cope with climate change disasters. I was taken aback because, having just emerged from a crash course in the negotiations’ early history, I knew that both proposals had been tabled – and junked – in the early 90s and yet, there they were, back on the table. I came to Bonn partly to get acquainted with recent developments in the negotiations, only to discover that they’re back where they started. Why are the negotiations stuck?

After interviewing over 20 people who have been closely involved in the negotiations from around the world and after poring over hundreds of pages of negotiating documents, part of the answer may well be because the two main blocs – the North and the South – have still not satisfactorily resolved the most basic but also perhaps the most fundamental question in the negotiations: Who’s to blame?

Indeed, beneath the increasingly arcane debates, it is still arguably this most mundane of moral questions that accounts for the most enduring standoffs: from the outset, most developing countries – from the most highly industrialized to the poorest – have accused the North of being guilty of causing climate change because of their emissions in the course of their industrialization. Most developed countries – for all the spats between Europeans and Americans – have remained united in rejecting this.

The US negotiating position has shifted over the years, but chief negotiator Todd Stern’s sentiments – “We absolutely recognize our historic role in putting emissions in the atmosphere, up there, but the sense of guilt or culpability or reparations, I just categorically reject that” – are the one thing that all decision-makers, whether Republican or Democrat, a true believer or a climate skeptic, a business lobbyist or a Beltway environmentalist, can agree with. Without fail, every US negotiator I have spoken with has repeated the line: we should not be faulted for something we didn’t know was (maybe) causing harm.

To be sure, parties have long agreed to contribute according to their ‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities,’ but this phrase has now become the most contested in the history of the negotiations: Southern negotiators tend to focus on the word ‘differentiation,’ convinced that its basis refers to the North’s historical guilt. Northern negotiators seize on the word ‘common’ and – in contrast to Southern negotiators who often stop at ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ – make it a point to add ‘and respective capabilities,’ i.e. they will contribute because they are more capable, not because they are obliged.

This is not just semantic swordplay because each side’s stance on the question of responsibility has oriented each side’s answers to three concrete questions that have dogged the negotiations: Who’s in charge? Who should do what? Who owes what?

Insisting that they’re the aggrieved ones, the South has pushed for greater voice in decision-making, has tended to prefer punitive and compulsory measures, and has consistently demanded ‘compensation’ from the North. Hence, the insistence on mandatory measures such as global taxes or fines for excess emissions. Rejecting guilt and insisting that they’re open to contributing more only because they can not because they should, the North has sought to restrict decision-making, demanded ‘flexibility’ or ‘cost-effectiveness’ at all times, through voluntary rather than compulsory measures if possible, and with rewards if necessary. Hence, the insistence on proposals such as ‘pledge-and-review,’ or mechanisms like carbon trading.

These diverging starting-points – linked to broader historical developments having to do with enduring North-South inequalities and the dynamics of global capitalism – help explain the failure to arrive at a common ground on many issues.

Efforts by the North to effectively confine the negotiations to only the big emitters instead of all 193 parties seem eminently reasonable to people like Berkeley economics professor Brad DeLong (who, in the same talk acknowledged that “many San Franciscans really won’t mind having the climate of Los Angeles”), since they believe that only those who will lead should decide. But this is unacceptable to those who care how justice is to be served: aggressors, after all, are not usually allowed to decide the terms of their punishment.

Demands for rewarding – rather than punitive – solutions may sound reasonable to those who see themselves as magnanimous leaders, but jarring to those who see them as guilty offenders: sinners, after all, are not usually allowed to ask for the most lenient form of punishment. Similarly, the North’s refusal to subject climate funds to democratic control by all parties (on grounds that the South could not be trusted) sounds eminently justifiable to those who see themselves as benevolent leaders, but absurd to those who hold them to be culpable transgressors: the guilty typically cannot avoid paying indemnity by assailing the moral integrity of their victims.

Even in the rarefied field of climate diplomacy, quotidian questions of guilt and innocence seem inescapable because our answers to them can define the terms of our social relationships with others, even or especially in situations of inequality. For two decades, the North and South have been struggling over those terms at every step: what each can justifiably demand from the other, what others can justifiably demand from oneself, what one is entitled to, what one is obliged to do, and so on.

To date, the North, with the support of some in the South, has succeeded in institutionalizing its claims of innocence, through the Kyoto Protocol’s guarantee of ‘flexibility’ and its resort to carbon trading, a mechanism that trumped the South’s earlier proposals for punitive fines and compulsory compensation.

But that doesn’t mean the question has been settled once and for all, as continuing demands for restitution, for an international climate court, or for ‘climate justice’ show. And as long as it is not satisfactorily resolved, the negotiations may remain stuck where they are for another 20 years. That may be fine for those perched in the Berkeley hills, but not for those stranded on the roofs of Bulacan.

Herbert Docena, Focus on the Global South, Philippines, and the University of California, Berkeley