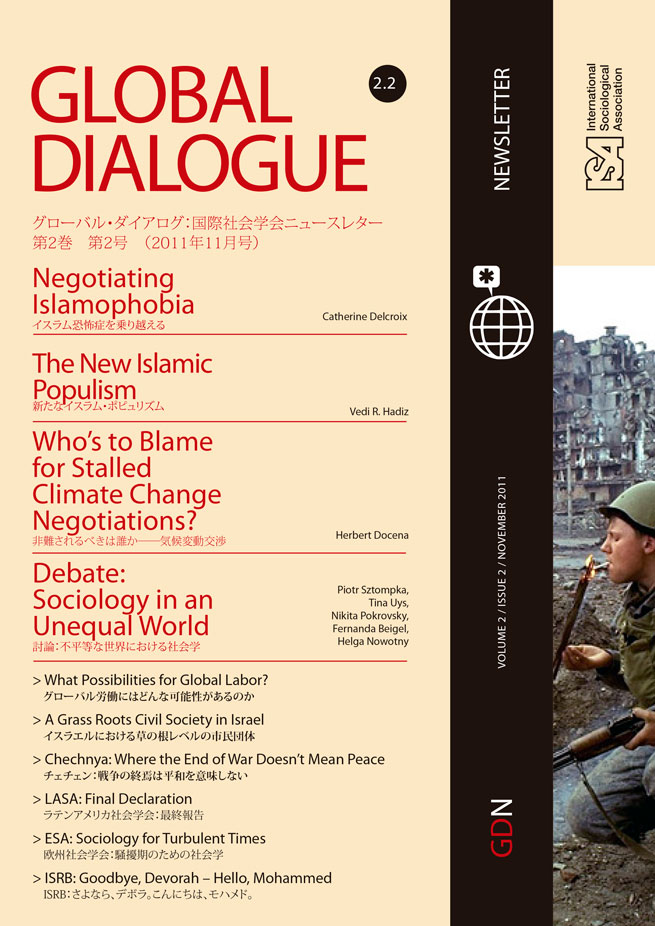

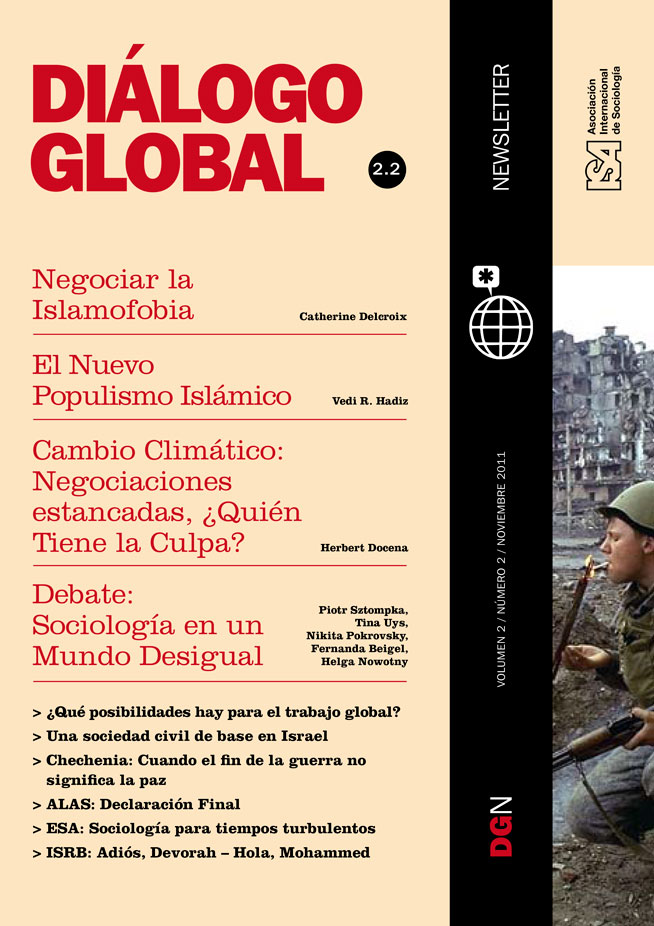

Luba Vladovskaja invited me to her dark, cold apartment in a Viennese suburb. After spending many long days and nights in the cellars and bomb shelters of Grozny, the capital of Chechnya, she asked her sons to find her an apartment with big windows. She got her big windows but they face a dirty courtyard and have cracked frames that cause draught and make the flat even colder. She shares this grossly over-priced two-room apartment with her son and husband. The couple was forced to leave Chechnya in 2008 and they were granted asylum in Austria. Their two sons had to flee earlier after falling victims to unlawful detention and torture. Their story shows that the end of war in Chechnya has not brought peace and stability to its civilians and that having asylum in a European country does not guarantee security and life without fear.

It is 17 years since the first Russo-Chechen war began and 12 years since the start of the second campaign. In 2002, the war was proclaimed over by the then president Vladimir Putin. Throughout the following two years, Russian citizens – mostly coming from Chechnya – constituted the largest group of asylum seekers in Europe. Austria accepted a large share of these applications. Russia continues to be among the top three source countries of asylum seekers in the European Union. Despite increasing rejection rates for people from the North Caucasus all over Europe, they still struggle to come.

In the 2000s, the administration of the country was handed to pro-Moscow Chechens in what was dubbed as Chechenization of the conflict. They were to conduct the ‘anti-terrorist’ campaign themselves. Receiving strong support from Moscow, the Chechens were gradually given substantial leeway to run the country. Thus, although Chechnya is part of the Russian Federation, it has its own parallel system of criminal code proceedings with unwritten rules that condone falsification of evidence and torture. Hundreds of people are becoming its victims. The local authorities have a distinctive way of investigating crimes. They first identify potential perpetrators and only later pick evidence which implicates them in the criminal act. This evidence is often flimsy and based on testimonies extracted through torture. But in the environment where most of the representatives of the criminal justice system are loyal to the pro-Moscow regime, it is an efficient way to deal with the backlog of cases and to secure one’s personal career advancement; all in the name of the fight against ‘Islamist terrorism’.

Luba’s son Mikhail Vladovskij was acquitted in 2005 after two years in jail. He was imprisoned for allegedly blowing up cars occupied by members of the armed forces. He was supposed to have committed these crimes together with another man whom he, in fact, first met in the temporary detention of the district police department in Grozny where they were both tortured. Given how typical the case was, the acquittal came as a surprise. Anna Politkovskaya and Natalia Estemirova, prominent human rights defenders (both later killed), wrote articles about the uniqueness of this Supreme Court decision. The judge simply decided to look more closely at the evidence and the case fell apart. As Mikhail was recovering from his many injuries, it was clear that he and his brother, who was also tortured to give evidence against Mikhail, would have to leave the country to avoid another imprisonment. Indeed, the Prosecutor’s office successfully appealed against the acquittal. After their departure, Luba kept trying to prove Mikhail’s innocence and to bring his torturers to justice. This soon became dangerous. She had to endure numerous visits by the armed forces to her house and was shot at from a passing car. She understood it was time for her to leave too. After surviving the two wars in Chechnya, it was the process of ‘normalization’ under the Chechen authorities that made her leave for good.

After Luba had settled into her new home, her many illnesses started coming out. Back in Chechnya, she simply could not afford to deal with them. She spent a long time in hospitals. But fear can hardly be cured. She says it is so deeply inside her that she cannot get rid of it. Luba shivers even when her phone rings. Does she have a reason to be afraid? In 2009, Umar Israilov, a young Chechen man, who was also granted refugee status in Austria, was shot dead on a street in broad daylight in Vienna. He formally accused Russia’s government of allowing executions and torture of illegally detained people in Chechnya and pointed to direct involvement of the current Chechen president Ramzan Kadyrov in these practices. By killing Israilov in such a way, not only a court witness was eliminated but a very effective lesson was given to Chechen refugees. Mistrust pervades Chechen communities as numerous informants of Kadyrov’s regime are believed to operate in Europe. Those who carried out the killing were handed harsh sentences in Austria this year. The link to those who were suspected of ordering it remains unproven. As Kadyrov’s patron, Vladimir Putin, is bracing himself for another term as Russia’s president, the impunity in Chechnya is likely to continue.

Alice Szczepanikova, Alexander von Humboldt Post-doctoral Research Fellow, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany