Undoing Borders in Solidarity Cities

October 25, 2019

While the leaders of the EU member states are pushing ahead with migration policy restrictions, accepting the death of thousands of people in the Mediterranean Sea and criminalizing those who rescue refugees in distress, municipal governments of various European cities are declaring their cities “Solidarity Cities.” Cities have thus become a space of struggle and experimentation around the future of migration regimes, but also for a fundamental democratization of urban life in the sense of a right to the city for all. These struggles for “urban citizenship” show possibilities for cities to challenge not only the nation-states’ ability to draw and uphold national boundaries, but also the fundamental meanings of citizenship.

Bridges from the sea to the cities

A significant political intervention at the local level involves a commitment to a “city of refuge.” Progressive mayors in coastal cities of Italy (e.g. Naples, Palermo) and Spain (Barcelona) have spoken out in favor of opening their ports and have offered to welcome those rescued at sea. After hundreds of people drowned within sight of the Sicilian coast, Leoluca Orlando, the mayor of the Sicilian capital of Palermo, was one of the first in Europe to declare his city a “city of refuge.” Leoluca Orlando has generated Europe-wide attention with his sentence: “If you ask how many refugees live in Palermo, I will not answer: 60,000 or 100,000. But: none. Whoever comes to Palermo is a Palermoitan.” The “Charter of Palermo” he initiated demands that civil rights be exclusively linked to one’s place of residence.

In Germany, too, city governments have expressed their willingness to offer refuge for people looking for a safe home. Broad alliances (e.g. “Seebrücke” and #unteilbar) with thousands of people from across civil society have stood up for the creation of Safe Harbors through repeated demonstrations and creative actions. They call for safe escape routes, decriminalization of sea rescue, and a direct and humane reception of refugees, similar to a relocation program.

Access without fear to the urban infrastructure

Experiences from North America, specifically the Sanctuary Cities movement that has been developing since the 1980s, have been an inspiration for the Solidarity City movement in Europe. The central point of departure of Sanctuary Cities is the city’s illegalized residents. For undocumented migrants, the border is reproduced in everyday activities such as attending school, going to hospitals, or using public transport. Those who cannot prove that they have the correct papers are excluded from access to basic social services and can be criminalized, arrested, and deported.

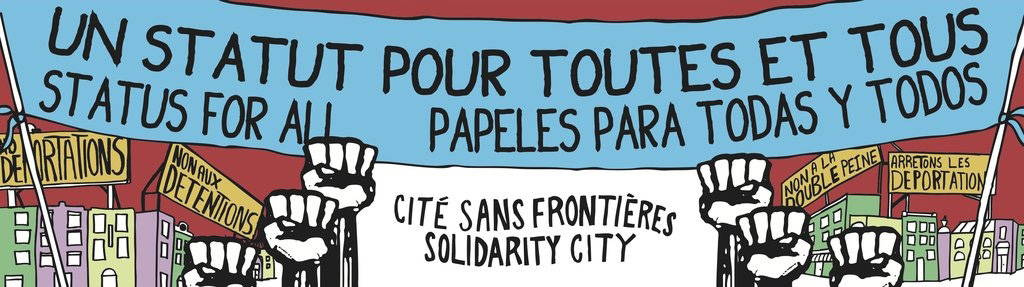

In order to protect urban residents from deportation and to grant access to urban infrastructure and social rights, different forms of cooperation between social movements and city governments, which together oppose the national authorities and their migration policies, have been tested. A “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policy (as introduced in Toronto) prohibits city employees providing public services from asking about migration status (“Don’t Ask”) and, if it becomes known, from passing it on to other state authorities (“Don’t Tell”). In some cities such as New York or San Francisco, everyone who can prove their identity and residence in the city is entitled to an official municipal identity card, which offers people without regular residency status more security in their everyday city life and facilitates accessing city resources.

Currently, activists of the Solidarity City movement are calling for the introduction of City ID Cards in various German-speaking cities (e.g. in Hamburg, Zurich, Bern), following the example of New York. The Bern city government has already spoken out in favor, although the access criteria and the concrete content of the card are still contested.

Undoing borders

City governments play a central role within the (internal) border regimes as the development and implementation of welfare services depend on the city’s interpretation of national regulations. While the restriction of social rights for migrants with precarious status constitutes a form of internal migration control, providing access to welfare services for irregular migrants at the local level can challenge the existing concept of national borders.

This reflects an expansion of the notion of citizenship: Citizenship is not only defined as a status but as a process which involves negotiation over access to and exercise of rights. This interpretation gives less importance to legal regulations but rather focuses on specific social relationships, norms, practices of solidarity, and the negotiation of belonging. It therefore becomes all the more important to focus on the actual sites where citizenship is negotiated in day-to-day life, and where new forms of solidarity are exercised within urban communities.

The problem raised here is not primarily migration, but the unequal distribution of social rights and unequal access to resources. This enables a shift in the discourse on migration – away from the current “integration imperative” and towards addressing inequalities and the question of social participation. In this lies the connection to current right-to-the-city struggles, at whose heart is the resistance against gentrification and against the commodification of public spaces, the collective appropriation of urban infrastructure, and participation rights.

Concrete utopia

What all these initiatives that mobilize with the slogan of a Solidarity City have in common is an evocation of a concrete utopia. This concrete utopia has the potential to lead out of political constraints by linking migration and social policy issues instead of playing them off against each other.

In addition, the concept of the Solidarity City enables broader alliances against poverty, for social housing, urban infrastructure, and cultural and democratic participation. Starting from very concrete needs and realities in urban space, everyday struggles of different social movements, which otherwise often operate separately, can come together and at best create a new awareness of jointly experienced forms of exploitation, oppression, and discrimination within a diverse urban precariat.

Often it is such concrete initiatives and grassroots movements that lay the foundations for certain political experiments. For a successful implementation, the creation of bridges between activists, progressive city politicians, and local authorities/administrations is crucial. However, the urban level should not be overestimated: Despite the room for maneuver, cities are integrated into a global power structure and the nation-state remains an important terrain for political struggles.

Finally, the concept also includes the opportunity to create a new understanding of belonging. It is not about who and how a perceived “Other” is and should be. Rather, it offers the possibility of collectively imagining a new “us”. This is a long overdue adjustment to the current reality of a post-migrant society in which migration is recognized as a fact.

Sarah Schilliger, University of Basel, Switzerland <sarah.schilliger@unibas.ch>