The Fragmented City: A Critique of Anti-Women Urbanism in Iran

July 16, 2025

Dealing with the place of women in urban development and their invisibility in the process of major urban decisions necessitates a comprehensive debate, especially when faced with a country with religious laws. This short essay will touch on a sample of the injustice that has been done to women in this context and delve into the stark difference between people’s lifestyle and what is written in laws and papers. My methodology is theoretical in nature, and by employing a critical lens, I aim to discuss the complex interplay between women, urban areas, and social justice within a specific cultural framework.

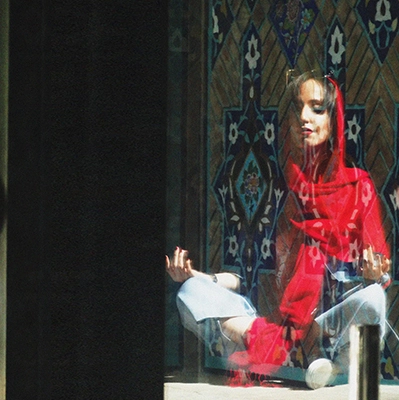

No sign can evoke a feminine environment

Approximately 20 years ago, in Iran, an urban plan called “Ladies’ Park” was proposed with the idea of strengthening women’s freedom and social vitality in the public space. The aim was to create a sense of security and comfort for women by allocating them certain sections of urban public space. Parks with lush green trees, fountains, and colorful flowers were designed, but the laws in force conveyed very different ideas, at odds with the fundamental goals of recreational spaces. As a result, except for a few individuals who sought to be present in these parks, the majority of women perceived the security and tranquility in these spaces as an artificial and unrealistic construct, imposed on them through a process that was oppressive and unjust.

The reason behind the failure of the plan and its lack of popularity can be found in the flawed assumption that certain things which are fundamentally inseparable can actually be separated. There are qualities that cannot be confined to a limited space; characteristics that must flow through the very DNA of a city. However, the attempt to assign a specific location to such dynamic qualities, and to imagine capturing what is perpetually in motion, only led to a sense of disconnection, and hence failed. In the same way that there is no need for a sign or label to evoke a sense of masculinity in the city, the mere presence of a sign at the entrance to a park was insufficient to create a feminine environment.

Intangible and fluid qualities confined within boundaries lead to fragmented emotions

When the allocation of public spaces is considered for creating a sense of vitality and enthusiasm in specific areas of the city, similar problems arise. I am not suggesting that there is anything fundamentally wrong with the zoning of land for different uses. Here I am pointing to a more fundamental gap, namely the “emotional zoning” that is essential and ubiquitous, and fundamentally uncontainable. The existence of such qualities as satisfaction, delight, transparency, and familiarity with the environment, which are considered essential components of a healthy city, is not subject to any law or regulation.

When the spatial system is compartmentalized by allocating specific geographic areas to these intangible and fluid qualities, instead of enjoying them as an integral part of the cityscape, we only allow them to manifest within limited boundaries, resulting in an ineffective and incomplete product. This means tacitly accepting that the city should be divided into segments, and expecting from each segment a specific behavior, but not beyond it.

Consequently, although the overall volume of “pleasant life experiences” increases with the expansion of public parks and recreational centers, a cohesive emotional landscape cannot grow throughout the city in these circumstances. Instead, there will be fragmented emotions scattered throughout the city, with no underlying thread between them, and citizens left with no choice but to search for and internalize them in specific locations in order to appreciate those feelings. Ultimately, one cannot expect moderate behavior from such an environment, and achieving collective satisfaction and contentment under such conditions is virtually impossible.

A city will always reflect its inhabitants, who cannot be transformed by hierarchical planning

The object of my criticism here is that such decisions aimed at reducing this chaos in reality only add to the existing malaise. By prioritizing visual order over the inner order of life, they create, despite their inherent disciplining nature, a new form of tension in tandem with familiar and legitimate motifs such as law and conventional contracts. In fact, it is precisely for this reason that rigid and static zoning schemes, which neglect the dynamic nature of human behavior, are doomed to fail: they are either rituals of display and magnification of a trait that is rarely found, or methods for avoiding responsibility.

Such a hierarchical system, which remains silent in the face of social inequality and seemingly strives to measure all individuals against a single, fixed standard, ultimately gives rise to a segmented society, divided into distinct classes, where some are content with the order imposed upon them, while others are left out. In this scenario, poverty emerges as an intractable problem, behavioral violence as well as crime and delinquency become commonplace, and widespread satisfaction turns into a rare and precious jewel.

This suggests that the hierarchical structure determined by one’s physical location, first and foremost, leads to gradual changes in a person’s mental state. In fact, these urban rules should first be aligned with the existing cultural norms, values, and social codes of a city, rather than expecting the city to conform to their unfamiliar instructions. Consequently, despite the necessity for laws and regulations to control urban development, the lack of existential meaning and commitment to the unique characteristics of the host community will render them invalid and valueless, making cultural transformation an unrealistic expectation.

Armita Khalatbari Limaki, independent researcher, architect, and designer, Iran <armita.khalatbari@yahoo.com>