The discussion around decoloniality and indigenous sociology gained popularity in the 1990s; however, from the beginning, sociology in India has emphasized the importance of indigenous concepts and viewpoints. This emphasis can be traced back to two contexts: firstly, the socio-political context, and secondly, the intellectual–ideological context.

A sociology founded on the interplay between the freedom struggle and Western intellectual traditions

The development of sociology as an academic discipline in India began in the early twentieth century, paralleling experiences in France, Britain, and Germany. The first sociology department in India was established in the same year as the sociology department was founded by Max Weber at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich: 1919. However, plans to create the sociology department at the University of Bombay were made before World War I in 1914. The Indian Sociologist, the first Indian sociological journal, began publication in London in 1905, founded by Indian freedom fighter Shyamji Krishna Verma, the same year Sociological Papers was released, which eventually led to the creation of The Sociological Review in 1907, marking the first sociology journal from Britain. Another journal from India, The Indian Sociological Review, was established in the 1920s by a British-born American philosopher from Baroda. It is worth noting the divergent backgrounds of the editors. The foundation of sociology in India is marked by a dynamic interplay between ideological preferences stemming from the freedom struggle and the expanding influence of Western intellectual traditions.

Despite India being under British rule and having foreign beliefs, knowledge agendas, and educational systems forced on it, the 1920s were characterized by major political and social transformations, including a surge in the political consciousness of the idea of unity against British rule, the anticolonial independence movement, peasant movements, and labor strikes. This decade also witnessed the implementation of the repressive Rowlatt Act and the self-governing Government of India Act of 1919, alongside the rise of movements like the Khilafat, the non-cooperation movement, and the establishment of trade unions. The All India Trade Union Congress was founded in 1920, followed by the formation of the Communist Party of India in 1925. As the freedom movement gained momentum in the late 1920s, it began to mobilize large groups and lead major protests. Furthermore, organizations representing “low castes” started to assert their presence, criticizing the dominance of “upper castes” and securing some reserved seats in the Madras Legislative Council.

All these mobilizations, movements, and organizations were mainly led by an emerging middle class educated in European traditions, yet drawing vigor for resistance from its indigenous heritage. Another section of the educated middle class was engaged in professions related to academia and intellectual pursuits. Against this backdrop of political upheaval, efforts to integrate indigenous perspectives into the liberal arts, social sciences, and political theories can be seen at the intellectual level.

A long history of multifaceted philosophy

The indigenization of sociology can also be framed within a philosophical and intellectual context. India’s philosophical and intellectual legacy is among the oldest and most diverse, encompassing numerous schools of thought and a broad spectrum of themes. Historically, Indian philosophy has not only been shaped by but has also influenced the cultural, spiritual, and intellectual currents of the Indian subcontinent. Different schools of Indian philosophy have offered unique perspectives on metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and spirituality; emphasizing ways to shape everyday social life, norms, and values.

Throughout the medieval era, Indian philosophy experienced significant growth and a creative fusion between Hindu and Muslim thought, along with the emergence of the Bhakti and the Sufi movements, leading to a more varied cultural landscape. In recent times, public scholars and personalities have connected ancient insights to existing issues, advocating ideas such as universal brotherhood and non-violent resistance. The multifaceted nature of Indian philosophy represents a rich interweaving of various elements, each contributing to a deeper comprehension of existence, society, and the universe. This legacy not only mirrors the past but also seeks to understand the present. It has influenced the development of sociology in India specifically, and has also shaped political and ideological thinking more broadly.

Sociology for India or sociology of India

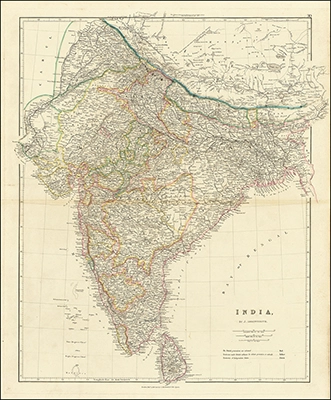

In these two contexts, Indian Sociology has consistently engaged with the discussions of indigenization, contextualization, and Europeanization centered on the academic hubs of that era, Bombay (Mumbai), Calcutta (Kolkata), and Lucknow. Initially, sociology in India occupied a subordinate position in its institutional development, often seen as a leftover discipline compared to anthropology, economics, philosophy, and civics. However, the sociological practices at Bombay (Mumbai), Lucknow and Calcutta (Kolkata) sought to establish an independent trajectory, using concepts and perspectives that were grounded in Indian realities, while also preserving their unique viewpoints.

In this regard, three distinct approaches aimed at integrating indigenous perspectives within broader sociological approaches can be identified. The first approach is traditionalist and completely rejects the Western sociology paradigm, asserting that the unique characteristics and distinct nature of Indian society can only be understood and described through a long-established classical philosophical perspective and employing indigenous concepts, which are now referred to as the Indian (Hindu) knowledge system. The second approach is strictly sociological and focuses on applying Western sociological frameworks and methodologies to both generalize and specify the characteristics of Indian society. The third perspective aims to merge the dynamic features of Indian traditions with Western traditions, recognizing the impact of Western social theory and philosophical practices while integrating the Indian philosophical viewpoint and cultural diversity in Indian society. This can be observed in an effort to triangulate the Vedantic philosophy, hermeneutics, and Marxian dialectics to explain the rationalization of Indian tradition.

While the first approach represents a closed monologue, the third promotes a dialogue between indigenous perspectives and Western sociology, creating a global conversation. It is relevant to acknowledge that a captivating debate unfolded among leading Indian sociologists representing two contrasting perspectives: “Sociology for India” and “Sociology of India.” This dialogue focuses on whether sociology should concentrate on the study and interpretation of Indian society specifically or whether it should take a wider perspective that includes all societies, India being one of them. Recently, there has been a call for a discourse on postcoloniality, which may not yet have come to fruition.

An ongoing and evolving conversation between indigenous and Western sociology

In the period since independence, the integration of Indigenous perspectives with European methodologies in the social sciences has gained significance in India, acknowledging traditional knowledge systems and cultural practices while also appreciating the utility of Western sociological approaches to analyze contemporary economic changes, political shifts, and societal transformations. Frequently, Western sociological frameworks overlook the distinct social systems found in India, thereby emphasizing the necessity to decolonize academic viewpoints and disciplines in post-colonial India in order to foster intellectual autonomy. In this context, the insights from Indian sociologists emphasize the importance of examining cultural practices, diversities, rural communities, caste structures, kinship ties, ethnic identities, caste discrimination, agrarian movements, social activism, societal changes, and economic progress. This was especially true in the period following independence, by proposing novel concepts and models that promote comprehension of Indian society through its historical, cultural, and traditional perspectives.

Although the Hindu system of knowledge is distinct and creatively integrates with various oriental perspectives, there exists an undeniable appeal in the Western knowledge system and its practical use. In this context, the themes, concepts, methods, and theories of Western sociology remain prevalent, despite a robust tradition of indigenization and contextualization. One could assert that the conversation between indigenous sociology and Western sociology has been ongoing, reflecting the progress of the discipline.

Additionally, the process of indigenization amid globalization is evolving, with emergent research areas like Dalit studies, tribal studies, and gender studies framed within subaltern and critical theory approaches. Indian sociologists contribute to global sociology by offering indigenous insights into traditional societies as they navigate the transition to modernity. Although sociology has traditionally been a social science primarily developed in the West and remains largely influenced by Western paradigms, it would be misleading to assert that Indian sociology has been decisively dominated by Western frameworks throughout its history, whether during the colonial period or after independence.

Since its inception, there have been initiatives to recognize the importance of indigenous viewpoints and ideas. This is evident in the diversity of viewpoints present in works that are either firmly based in Indian knowledge traditions or shaped by Western sociological concepts while remaining rooted in the Indian context. Despite the ongoing difficulties of merging traditional values with contemporary practices and indigenous perspectives with global influences, persistent efforts are essential to strengthen indigenous sociology and to integrate indigenous insights into global sociology.

Rajesh Misra, University of Lucknow, India <rajeshsocio@gmail.com>