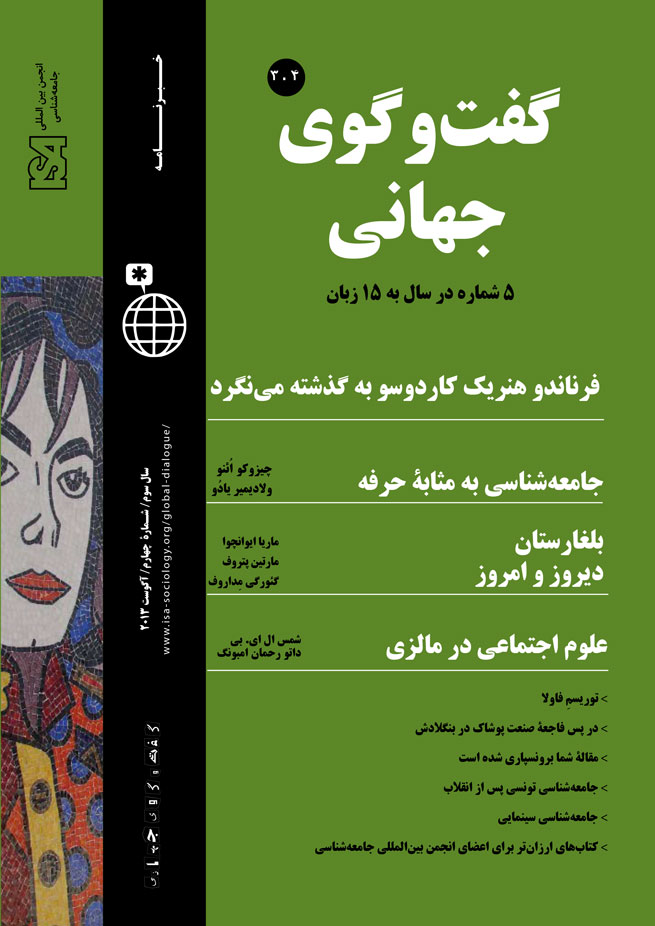

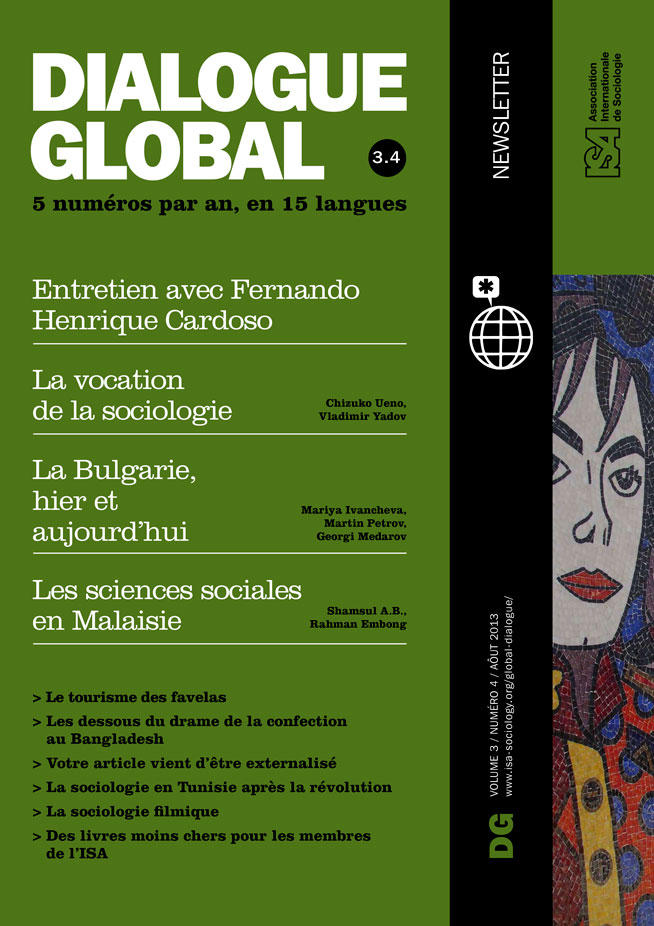

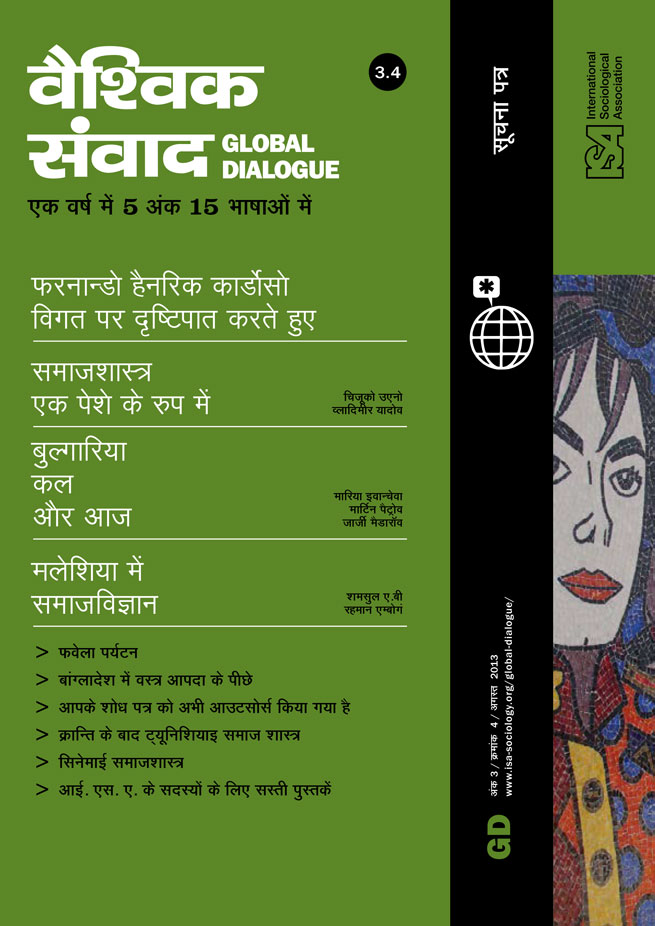

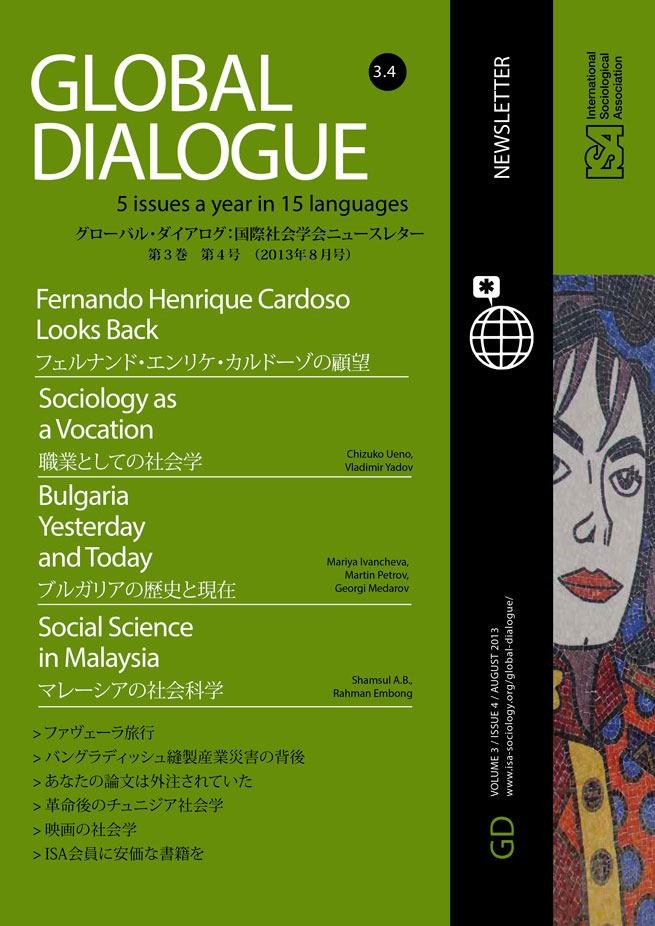

President as Sociologist An Interview with Fernando Henrique Cardoso

August 17, 2013

After being Minister of Finance, Fernando Henrique Cardoso was elected President of Brazil for two terms, 1995-2003. He was President of the International Sociological Association (1982-1986), toward the end of the Brazilian dictatorship. He was already then a world-famous sociologist with pioneering work on the interaction between dependence and development in Latin America. His dissertation was a classic study of slavery in southern Brazil. The interview here is based on remarks he made at the closing session of the meetings of the American Sociological Association in 2004, one year after he left the office of President.

MB: President Cardoso, how has being a sociologist shaped your experience as a President, a President of a country, and not a small country but the huge country of Brazil?

FHC: I would say that I believe that what is important in political life, as well as in academia, is to believe in something. If you don’t have a vision, if you don’t take a stand it is impossible to leave an imprint on a community or a country. You must have convictions. This is probably the opposite of what has always been said about “political man.” Of course I read, as you do, Weber. And Weber made the distinction between the ethic of conviction and the ethic of responsibility. But he never segregated each one as the driver of political action. Instead, he took both ethics into consideration. He himself was a German deputy, and highly nationalist. So he had values.

Provided you have conviction, and provided you are able to express it at the appropriate time – that is to say, when your time in politics coincides with people’s sensibility – one can become a political leader. Without that capacity it is impossible. You can be elected, but without conviction, without profound convictions you cannot become a political leader. And in my case, I would stress that what moved my generation was not our passion for economic development, although we had that. Democracy was our main devotion.

At the time when I became directly involved with politics we were still living under an authoritarian regime. We suffered daily from the lack of freedom. You could see people being exiled, or people in prison – people being tortured: that was the main incentive for our engagement. This implied the reaffirmation of our democratic creed, of our democratic convictions.

MB: Democracy is a vague and abused word, what does it mean to you?

FHC: You have different types of democracies, different variations of the same value, with different configurations. In today’s world democracy is not just about being able to engage with a political party and in electoral life. I must say that I never was a party member in the proper sense. I never was an apparatchik. I hate apparatchiks. Once in my first political campaign for the Senate I said in a speech to a room full of members of my political party – that opposed the military – that militants are boring people. I don’t think that you can look at politics just in terms of political parties. I think nowadays what is important is to have the capacity to get in touch with ample sectors of society in general, and to express values in accordance with the diffuse sentiments of people.

So to be effective as a “political man” requires some capacity to seduce, to communicate, to generate emotion. To some extent you have to be an actor. In a good sense of the term: not because you are playing a role as in a theater. It’s not that. You have to have the capacity to communicate and feel emotion, and to transmit emotion. Maybe I became a political leader because I like people. Being president I tried to be in contact with ordinary people. Presidents tend to be very distant from simple people in general. But presidents have waiters. We have people who take care of us, even when we are in the swimming pool. We have drivers. We have security guards. These are the people surrounding a president in day-to-day life, not just politicians and upper-class people. I tried to talk to them, and to give them the feeling that they could speak to me as a person. Not as a president. And I tried to listen to them as to how they really felt about different things. I think nowadays what is important is not to be an actor, in the sense of a performer, but to be able to influence affairs by transmitting emotion that shows you are genuinely committed to what you are expressing. This also requires not losing the sense of being a human being.

MB: And sociology, does that help you to be human?

FHC: Sociology helps a lot. Very often in Brazil people competing with me – my adversaries – used to say, “Well, this is a man who was never poor in his life. He speaks better French than Portuguese.” They said things like that just to disqualify me. But they missed the point. Being a professor in foreign countries, as I had been, taught me a lesson: I had to speak more simply and directly than ordinary intellectuals do.

I remember when, as an exile from the military dictatorship, I started giving classes in Chile. Portuguese and Spanish are very close, but they are not the same language. Brazilians understand Spanish, but not the other way around. The Chileans protested at every word I tried to pronounce in Portuguese. So I was obliged to avoid complex words, I had to simplify.

Also as a sociologist it is important to be – and you are trained to be – in contact with people. And when the opposition said “Oh, this man has no capacity to relate to poor or simple people,” I smiled because I started my career as a sociologist living with black people and dealing with race relations. So I visited lots of slums and favelas, shantytowns in the southern part of Brazil. Later I conducted research with workers. Then I moved to the study of entrepreneurs. But I started my career in close contact with simple people. So I never had difficulties in dealing with people.

I had also followed courses in anthropology. We actually studied the three disciplines together: sociology, economy, and anthropology. And you know how anthropologists are – my wife was an anthropologist –, they look at very specific things. And they like to talk to everyone, take notes, reflecting on small changes in behavior. It is important for a politician to have the capacity to understand others and dialog with them. This enhances one’s ability to influence others, provided you have the capacity to be an actor, in the sense I stressed before: to express your true sentiments in a straight and sensitive manner.

MB: But can sociology also be a handicap?

FHC: Yes, indeed. I remember I was shy when I started my first political campaign running for a senatorial seat. To run a political campaign in Brazil means to touch people. And they grab you back with great force. At the end of the day you are really very tired, exhausted by so much passion. A political campaign – at least in Brazil – is a physical interchange; it’s people to people. It’s not just talk. You have to touch. You have to be close to people. This requires some training. So when I started it was not easy.

But, of course, talk is important and it’s not easy for an academic to speak to crowds. You have both to simplify and be very affirmative. And not try to make great statements, because people just don’t like that. It is not easy for an academic to adapt to that situation. I remember at the beginning I tried to give a different speech at each meeting I addressed. And, don’t forget, in a political campaign we have in one day perhaps eight or ten meetings. I was ashamed to repeat the same ideas. So I tried to imagine different stories for each audience. This was a disaster.

Because no one really gets what you want to convey, you have to repeat yourself again and again. You have to simplify and repeat. So in those circumstances it’s not easy to be a sociologist and a politician. But when you move from that situation to TV then we have an enormous advantage. In my first electoral campaign for a seat in the Senate to represent the state of São Paulo – at a time when Brazil was still under the military rule and we were campaigning against it – I went on a TV network to debate with my opponent. I was rather calm throughout the debate. That was because I was trying to give a lesson, or something like that.

When I went back home my friends were in state of total despair; this is impossible, they said, you don’t have the energy, you don’t transmit the feelings that a politician must express. The actual impact on the audience was quite the opposite of this pessimistic analysis. Because TV requires much more a kind of dialogue – a more intimate conversation than public speech at a meeting – so we have this additional advantage, being sociologists and teachers, we have mastered direct dialogues with students. For us it’s not that difficult to take advantage of TV in political life. It is enough to perform as a good teacher, expressing your ideas in a simple and convincing way.

MB: As President how did you deal with political parties?

FHC: In the case of Brazil, as I said before, what is really important is the capacity that leaders have to present a vision to the nation – not to the parties. The leader must convince the majority of the population, even at the cost of bypassing the political parties.

Parties, very often, are more likely to block than promote change. They’re not prepared to deal with innovation. So you have to bypass the party structure. At the same time, you have to realize that ultimately you depend on the political structure to succeed. This means you cannot go against it. If you enter into direct conflict with the political system you run the risk of ending up as some kind of dictator or of being impeached.

You can manipulate the masses and mobilize them against Congress. Using TV this is not too difficult. But this path leads toward dictatorship. You need to have a firm democratic conviction and not turn the masses against Parliament because Parliament can be an obstacle to the changes you are trying to implement. You have to be prepared for permanent negotiation with Congress. Here again being a trained sociologist has some advantages, because you understand what are the real interests at stake – not just by looking at the different parties, but by looking at the different groups and circles or even persons within each party. And, on top of that, and more importantly, keeping your eyes on the public interest.

MB: You had your fair share of national crises. What have you to say about responding to crises?

FHC: You have to always keep your cool in times of crisis – for example, in the moments of wild speculation in the international financial system – and steady the course, otherwise everything may collapse, which can sink both you and your government. Having the analytical capacity to understand the broader picture in times of crisis helps you to keep cool. You must be able to act at different levels, close to people in some circumstances and with the capacity to be aloof, so as not to rock the boat, but rather provide a roadmap and steer a course toward where you want to go.

In these moments, the prime duty of the Head of State is to safeguard the long-term interests of the Nation without which it risks collapse. And when this happens rebuilding the whole system takes a lot of time and always implies that the people will end up paying a huge social cost. That is also why it is so important to have the capacity to surf when the winds are favorable, seize the opportunity and forge ahead. This will also make you stronger in dealing with the bad moments when most of all you have to prevent the disintegration of the whole system.

To what extent is this tied to sociological training? To a large extent, I would say. Of course, there are other characteristics related to personal biographies, and to other kinds of capacities. But basically I would say that our training as sociologists gives us a broader horizon, gives us the capacity to understand the interplay between different groups and also gives us some sense of relativism, the realization that there is not one overriding truth or unique way of doing things.

MB: Have you any final sociological thoughts on the political process?

FHC: In my view the political process in contemporary democracy requires a permanent process of deliberation. Going back to Rousseau’s idea of a general will, I would say that nowadays the general will is redefined everyday by everyone in society. We must open space for this to happen, so that more and more people can engage in the process of deliberation. People no longer accept representation just in terms of the vote. Legitimacy today is not only linked to voting; it requires a permanent reaffirmation of the values and the cause you care for, you are struggling for.

I have several times received many millions of votes. I was twice elected for the presidency with the support of more than 50% of the electorate. But this awesome mandate is not enough. You need to reestablish, to reaffirm your legitimacy on a daily basis. It’s almost as if each day you are starting from scratch. Those who think that they have gained people’s trust once and for all deceive themselves. You must keep and renew this trust continuously by the reaffirmation of the values that guide your action.

So I will give you one last and only piece of advice: don’t enter politics – it’s very difficult!

Michael Burawoy, Editor of Global Dialogue

Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Brazil