Polarization and Political Conflict: Insights from Latin America

March 14, 2025

Latin America has been experiencing a period of growing discontent and social and political conflict since 2019, aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, as discussed by Gabriela Benza and Gabriel Kessler. The leftist forces that had fanned the winds of change at the beginning of the twenty-first century became the “establishment” to be challenged. At the same time, the emergence of right-wing opposition presaged a political turnaround; but this shift did not occur. Political discontent has grown in Latin America since the end of the commodity boom and has deepened with the pandemic. Expressions of this include massive protests, changes in electoral behavior, negative attitudes toward democracy, and the emergence of radical right-wing proposals.

Against this background, there are two questions we wish to address. How is conflict organized in different countries? What are the consequences and challenges of these conflicts for democracy in the region? To answer these and other questions, the Polarization, Democracy, and Rights in Latin America (POLDER) project, funded by the Ford Foundation, conducted comprehensive comparative research in five countries (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, and Mexico) between 2021 and 2023, using mixed methods.

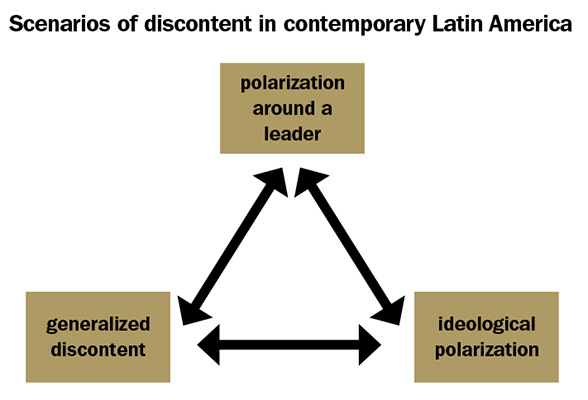

Based on our research, we argue that, after the end of the commodity boom, social conflict in Latin America can be framed under three types of scenarios: ideological polarization with affective components, polarization around an emerging leader, and generalized discontent. These three types are dynamic and do not follow a pre-established sequence, as shown in Figure 1.

Analyzing three cases: Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico

Among the countries studied within POLDER, Argentina and Brazil are cases of ideological polarization, as is Uruguay. There is generalized discontent in Colombia, as there is, with nuances, in Peru and Ecuador. The cases of polarization around a leader are those of Mexico under Andrés Manuel López Obrador and El Salvador under Nayib Bukele. We will consider three cases to illustrate these scenarios.

In Brazil, polarization began in the first decade of this century with a “left turn” built around a solid socio-political coalition comprising an alliance between the Worker’s Party (PT in Portuguese), unions, and social movements. The PT governments, as Singer argues, laid out redistributive policies together with progressive cultural, gender, and human rights policies. Samuels and Zucco show that when Bolsonaro emerged on the electoral scene, he managed to represent a dispersed and heterogeneous electorate that was brought together both by their rejection of the PT and, as also proposed by Santos and Tanscheit and Rennó, by their disagreement with a mainstream right wing that did not fully represent cultural and economic unrest against Lula and his party.

In Colombia, Botero, Losada and Wills-Otero demonstrated that Álvaro Uribe emerged in 2002 as an authoritarian alternative to traditional party candidates (despite being a Liberal Party leader). Within the frame of “democratic security,” he built a successful party brand based on hard-line policies on domestic armed conflict. The 2016 referendum on the peace accords was characterized by a high degree of electoral polarization and by a strategic joining of those opposed to the accords and religious conservatives. However, the non-partisan nature of the vote hindered the consolidation of socio-political coalitions likely to frame different agendas for voters. In 2018, a leftist electoral option at the national level reached the second round of the presidential elections. In 2022, this force brought its leader, Gustavo Petro, to power.

After more than 70 years of predominance of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (“Institutional Revolutionary Party”, known as the PRI), Mexico entered the twenty-first century undergoing a process of democratic opening up. A competitive system with three main electoral forces emerged: the PRI, which maintained its strength as a catch-all party with diffuse ideological components; the Partido Acción Nacional (PAN: “National Action Party”), a conservative party; and the Partido Revolucionario Democrático (PRD: “Revolutionary Democratic Party”), a center-left party. During the 2006 presidential elections, the PRD became absorbed within a new movement, this time with a solid re-foundational tone: the Movimiento de Regeneración Nacional (Morena: “National Regeneration Movement”) took in a good part of the PRD’s leaders and its rank and file. Morena’s leader, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (also known as AMLO), became president in 2018 with a discourse against the political establishment and its “privileges.” In 2024, Claudia Sheinbaum, of the same party, was elected with a high percentage of votes.

National scenarios and discontent at the societal level

How do different national scenarios influence the structuring of discontent at the societal level? In our argument, in line with Ken Roberts’ discussion of the post-neoliberal political scenario in Latin America, we see the agents of representation as providing the frameworks within which society organizes discontent. For example, in the case of Brazil, Kessler, Miskolci and Vommaro show that PT voters have progressive positions on cultural and economic issues. Bolsonaro voters are more conservative along both dimensions. In scenarios of generalized discontent towards political elites, parties organize the electoral scene but are weak agents of representation and, therefore, do not organize the conflict at the societal level. This is the case in Colombia, where Kessler et al. show that electoral preference and ideological positions are weakly correlated. When a polarized scenario centers on a leader, this polarization operates at the electoral level but does not organize preferences and demands within society’s principal agendas. As in Colombia, electoral preference and ideological positions are weakly correlated in Mexico.

The three scenarios we have defined also have implications for different dimensions of structuring conflict. The first obvious impact is on the politicization of agendas at the societal level. There is a correlation between a high level of polarization and a greater interest in politics. Opinions are clearly in line with votes. These ideas are related to the frameworks offered by socio-political coalitions. Brazil has more arguments and language about rights and less based on individual criteria. In both Mexico and Brazil, there is more interest in politics and more consumption of political information. On the other hand, Colombia is the least politicized case, with greater weight given to religious frameworks and less consumption of political information.

Second, there are implications for the ideological alignment of discontent. High levels of alignment imply that the frameworks organizing positions on agendas follow the left–right division (with its national particularities), generally associated with the main competing socio-political coalitions. In Brazil, where there is ideological polarization, an ideological boundary between voters of the two competing options can be identified. In Colombia, generalized discontent prevails. The lack of opportunities and the negative view of elites generate the perception of an uneven playing field: everything is set up by the elites only for their own benefit. This idea of an uneven playing field generates apathy and anger. In Mexico, the critical factor is moral and calls into question the protagonists of Mexico’s recent history, particularly concerning corruption and privileges.

The degree and content of affective polarization also vary in the three scenarios. Brazil exhibits the highest levels of moral disqualification of the adversary with ideological polarization. Thus, affective polarization feeds back into ideological alignments instead of supplanting them. A clear contrast can be observed in Colombia, where the negative view of the other only emerges among small, hard-core groups of voters. In Mexico, meanwhile, ideological alignment is also diffuse. Still, the figure of AMLO could either give rise to an ideological reordering of society or become a less durable experience of populist interpellation.

Conceptualization of scenarios and polarized situations

The dynamic character of our conceptualization of scenarios has implications for polarized situations. Polarization is known to have unequal effects on democratic vitality. It organizes discontent and creates high levels of politicization, but it also generates a great deal of animosity at the societal level.

Scenarios of polarization around an emerging leader can provide room for the growth of authoritarian orientations. This has not been the case in Mexico, where the presidency of Claudia Sheinbaum seems to augur a deepening of democracy. However, other cases of emerging leaders promising to transform long-standing discontent into hope for change may be worrying signs of illiberal democracies, as can be seen with Bukele in El Salvador, or a turn to the far right with an uncertain future, typified by Milei in Argentina.

Finally, cases of generalized discontent seem most common in Latin America. The dissatisfaction with democracy, the low level of participation in elections, and the difficulty for society to transform its dissatisfaction into transformative action point to a scenario of high political volatility with no clear horizon for change.

Gabriel Kessler, Conicet-UNLP/UNSAM, Argentina <gabokessler@gmail.com>

Gabriel Vommaro, Conicet-UNSAM, Argentina

* A prior version of this article was published in The Review of Democracy.