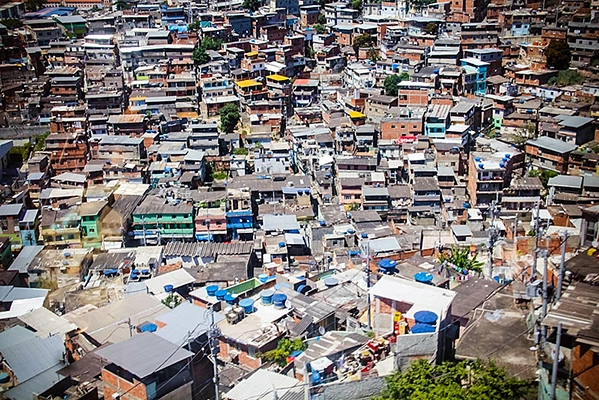

In this article we address how residents of a favela area known as the “Complexo da Maré” (Maré Complex), in the city of Rio de Janeiro, experienced price increases, particularly in food and energy, during 2021 and 2022, still in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. We use the concept of alignment (and its derivatives, such as misalignment and realignment) to analyze the different ways of navigating an increase in the cost of living through accommodating material changes and future perspectives at different scales: from the ideals of a good life desired by people and families, to decisions that need to be taken immediately or in the near future. We call alignment work the daily activities through which people and families dealt with the instability of income, variation in money flows, management of frustrations regarding the restrictions imposed by inflation, and the maintenance of significant ties, which were placed at risk or altered by the crisis. These activities involved, for example, constantly assessing price differences, moving around in new ways in the city, (re)classifying expenses, and changing the way products were bought and sold. Thus, alignment work is a combination of ways of imagining, calculating, projecting, and living together, articulated in evaluations about what, how, where, and why to buy or sell.

Extraordinary events and ordinary lives

The COVID-19 pandemic, together with the corresponding economic contraction and increases in the prices of basic goods were experienced in diverse ways, revealing distinct means of coping with extraordinary events through the flow of ordinary lives. For some of the people we spoke to, during this period things were not so different from their permanent routines of instability, poverty, and struggle. This allowed them to activate strategies cultivated throughout their lives and across generations. For others, inflation and a loss of income combined with other events, such as illness and death in the family, accentuated a feeling of exceptionality. For still others, the pandemic and the ensuing increase in prices opened up new possibilities and opportunities. These variations are at the heart of the differential process of producing inequality that is linked to inflation and a rise in the price of foodstuffs – considering that, in the Maré Complex, the first three items on the family budgets are, respectively, food, debt repayment, and residential services.

In terms of both mobility (which was restricted by policies aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19) and the instability of income sources, the lives of those we interviewed are molded by temporalities that are at once disruptive and recurrent. However, even in such a context of routinization of crises, price spikes (particularly of food and cooking gas) hit at the heart of the principal space where the reproduction of life is acted out: the household. This is why times of inflation demand intense and specific realignments (between the reality of domestic economies, routines, and expectations), such as changes in eating and cooking habits, re-prioritizing of what one considers to be ‘basic spending’, re-converting income-generating activities, taking on debts, or using the many emergency aid packets provided by the government.

Houses are the main loci where the lives of those we talked to are reproduced, and the kitchen is the heart of the activities of care that make a home and the people who inhabit it. Thus, changes in the routines of buying, preparing, eating, and sometimes selling food are crucially affected by the rising price of food and gas. Houses (casas), in our view, are at the same time material, affective, and symbolic spaces, shot through by solidarity and tensions that are characteristic of ties of proximity, structured by gender and generational relations.

House money

Contrary to the image projected in the category of domestic, instrumentalized in statistical research in general and in food security surveys in particular, households are not isolated entities. They form part of networks and configurations of houses. The proximity or distance between them(or their greater or lesser relative isolation) is a crucial element in the construction of social distances. Moreover, houses are not only sites of consumption, but also places generating income through the sale of repair services or personal care and the preparation of food for sale. The residence itself, or a window or a room, can serve as a marketplace. Sales may occur occasionally or with some regularity and at times other members of the household or of the configuration of houses help out.

The key to describing the dynamics of households during a period of inflation, and particularly in the context of rising prices of foodstuffs and gas, is the concept of house money (dinheiro da casa): a native expression that allows us to study the different meanings of money and monetary practices from the vantage point of domestic spaces. The concept of dinheiro da casa designates a moral and practical nexus between people, money, and houses that places value on the communal or common needs for the maintenance of the house as a living processual space giving rise to expenses that are obligatory in nature and regular, such as rent, services, and food. It is hence possible to look at the strategies aimed at aligning disturbances in these different aspects (particularly the reduction in spending power) with a redefinition of what are considered necessities for (re)producing life.

An ethnographic critique of inflation

The concept of alignment occupies a central place in economic theories of inflation. The so-called monetarist perspectives explain inflation as an effect of the excess of currency on offer and the mismatch of expectations with rising prices. Visions considered to be heterodox explain inflation by identifying maladjustments in productive chains and disequilibria caused by distributive disputes. Based on the specific and daily experience of increasing costs of living of those we spoke to in the Maré Complex, and adopting a pragmatic perspective on money that considers the sensorial dimension of inflation, we propose an ethnographic critique of the concept of inflation itself.

Eugênia Motta, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil <motta.eugenia@gmail.com>

Federico Neiburg, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil <federico.neiburg@gmail.com>