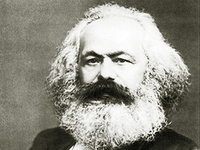

Marx’s ideas about the emancipatory and oppressive dimensions of capitalism have inspired scholars, politicos, and activists across the globe for over 150 years and have led to an entire intellectual tradition known as Marxism. Few intellectuals and radical actors have had such an impact on the world except perhaps Adam Smith, Charles Darwin, Mahatma Gandhi, Jesus Christ, the Prophet Mohammed and the Buddha.

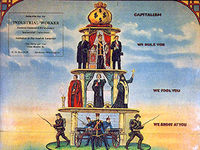

Marxism has simultaneously sought to understand and explain capitalism and also to resist it and change the world. In other words, Marxism’s contribution is twofold: (1) as a set of analytical ideas about the dynamics of capitalism; and (2) as an ideology and guide to political movements. The twentieth century was replete with Marxist movements, groups, and states, covering vast areas of the world.

The impact of Marx’s ideas

Let me start with the impact of Marx’s ideas. His ideas have influenced modern social theory, where he pioneered social enquiry about the nature of capitalist modernity. His influence extends across the social sciences, including sociology, politics, economics, media, philosophy, anthropology, and international relations, as well as in the natural and hard sciences (including geography and information technology) and humanities (the arts, rhetoric and literary studies, and education). After the 2008 economic crisis, even mainstream economists publicly acknowledged that Marx’s analysis of capitalism has much to teach us. Marx offers one of the most sophisticated analyses of capitalism, but it is not just the analysis of capitalism that has captured the left imagination. Marx’s concepts and implicit suggestions about a future post-capitalist order have inspired some of the most prolific and theoretically sophisticated thinking about socialism in the twentieth century and continue to inspire thinking about twenty-first century socialism, for instance in Latin America.

The other side of Marx’s influence is the impact of his ideas on political movements. Most of the twentieth-century alternatives to capitalism found their inspiration from Marx’s ideas about a future post-capitalist order. History is littered with examples of Marxist-inspired movements, but unfortunately many of these experiments have inglorious histories of authoritarianism, oppression, exploitation, and even genocide. Marxism in practice also has histories of sexism, racism, and upholding colonial relations. Today we also see China and Vietnam move to market capitalism in the name of “state socialism.” We cannot ignore or deny these histories.

Yet, Marx and Marxism have also inspired extraordinary movements and brought peoples from across the world together. The soviets in the Russian revolution, anti-colonial movements, and Cuba’s solidarity with the South African liberation movement and their brutal and deadly battle with the apartheid regime in Angola are such examples. Marx’s legacy is most profoundly represented in the way in which his ideas have inspired and galvanized people to think about and fight for a post-capitalist world – a world that is more egalitarian, just, peaceful, and free from exploitation and all forms of oppression.

Today, the rise of postmodernism with its anti-Marxist conceptions of power, social alienation, precariousness, inequality, and marginalization has re-ignited the importance of Marxist analysis. The recent revival of Marxism is not simply a return to nineteenth- and twentieth-century understandings of Marxism. For Marxism to endure, texts cannot be read in dogmatic and purist ways, and political practices have to move beyond vanguardism. Marx’s legacy endures through our continual renewal and reformulation of theory so that it can continue to help shed light on the world we inhabit. Just like feminism took on Marxism in the 1970s and theorized ideas such as social reproduction, intersectionality, and multiple forms of oppression, we need to engage the ideas of Marx and Marxists around contemporary issues of race, gender, sexual orientation, the importance of democracy for an emancipatory project, and the ecological limits and the global crisis of capitalism.

The case of South Africa

In South Africa, one of our biggest challenges is to bring Marxism into productive engagements around race and racism after apartheid. Marxism’s failure to address issues of race stems from the fact that early Marxists tended to view race as a social construction and a reflection of false consciousness. The issue of race repeatedly arose throughout the twentieth century within the national question debates in contexts such as the demise of the British Empire, the Russian revolution, decolonization, and the struggle against apartheid. As Marxists began to take up the issue of race, they tended to focus on the relationship between race and class, often reducing race to class and racism to its functionality within capitalist accumulation. Marxists have argued that racism divides the working class and needs to be challenged through a politics of solidarity among the working class. Marxism sees the universality in working class identity trumping the particularity of racism.

More sophisticated theoretical analyses examined the intersection of race and class by highlighting historical contingency as well as articulations between pre-capitalist and capitalist modes of production. In South Africa, the articulation between race and class took on a particular urgency with the apartheid state’s systemic race-based political oppression that converged with capitalist exploitation. However, despite the end of apartheid, patterns of racial oppression have continued in contemporary South Africa through a capitalism that has both eroded and reproduced forms of racial oppression. To understand the continuation of racial oppression within global capitalism, in South Africa and in many other places around the world, requires a new Marxist analysis, which is starting to emerge.

Conclusion

The ideas of Marx and Marxists will only continue to resonate in the twenty-first century if we are bold enough to engage, transform, and re-formulate them for our current times. New anti-capitalist movements are already doing this through bringing together post-vanguard Marxism with other anti-capitalist traditions such as feminism, ecology, anarchism, anti-racism, and democratic and indigenous traditions. These movements are not looking for a coherent ideological blueprint or a vanguard elite to lead them, but rather share the belief that “another world is possible” through democratic, egalitarian, ecological, and systemic alternatives to capitalism, built by ordinary people. This is in the spirit of Marx’s own inquiry!

(These reflections draw on two articles: Satgar, V. and Williams M. (forthcoming 2017) “Marxism and Class” in Kathleen Korgen (ed.) The Cambridge Handbook of Sociology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Williams, M. (2013) “Introduction” in Michelle Williams and Vishwas Satgar (eds.) Marxisms in the 21st Century: Crisis, Critique & Struggle. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.)

Michelle Williams, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, and member of ISA Research Committees on Economy and Society (RC02) and Labor Movements (RC44) <michelle.williams@wits.ac.za>