Fraught Fields: Doing Sociology in Violent Sites

February 25, 2022

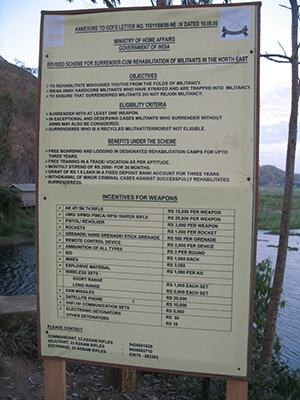

In this essay, I reflect on how sociology/social anthropology should examine state engendered violence. Resistance to the Indian nation-state project is one of the many conflicts that plague the country. The northeastern region, consisting of the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura, shares international boundaries with Myanmar, Bhutan, Bangladesh, China, and Nepal. This region has experienced the fallout of the nation-state project and has been marked by armed conflicts as part of self-determination movements. Consequently, the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 1958 (AFSPA) is operative in some form or the other in the states of the northeastern region (except for Sikkim). Introduced in 1958 in the then Naga Hills of Assam, AFSPA forms part of the political-administrative apparatus through which the region is governed. Special powers given to the armed forces to kill on grounds of suspicion suspend the right to life. Unsurprisingly, the hegemonic notion of the nation is not shared in this region where AFSPA fosters a culture of impunity, networks of rumor, and mutual suspicion.

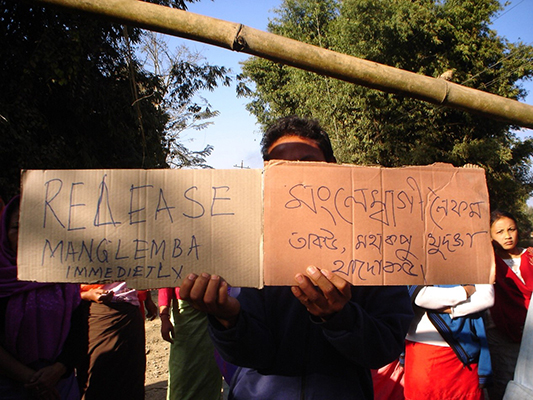

In Manipur, insurgent groups have increased from four at the beginning when AFSPA was imposed, to more than 32 groups (excluding various splintered groups). Many research works establish that years of using the military to solve political issues has ensured the impossibility of sequestering violence; it marks every aspect of life such that it becomes meaningless to attribute deaths as caused either by the state or the non-state. The Joint Stakeholders’ Report by the UN and the Civil Society Coalition on Human Rights (2016) reveals that 50,000 Indian soldiers are deployed in Manipur for a population below 3 million. The Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis states that between 2000 and 2004, 450 civilians were killed by militants in Manipur. Such statistics present Manipur as a space where the nation-state has failed to impose order. The challenge lies in discerning this space made disordered by state laws/policies.

Challenges for the ethnographer

Ethnographic fieldwork is central to the discipline as taught in the curriculum in India, where the distinction between sociology and social anthropology is blurred. In the framework of M.N. Srinivas’s school of sociology, the field is accessed through ethnography. The researcher participates in the everyday life to extract meanings people give to their lives. This assumes the field as that “natural setting” where the researcher claims familiarity as an insider. The insider/outsider identity is ambiguous (though broadly, in the northeastern region “outsider” refers to those who do not belong to a community of the region). Being a member of the same ethnic community or from the northeast more broadly usually makes one an insider. However, despite being from the same community/region, one can still be considered an outsider based on kin or political affiliations.

One of my research aims in Manipur was to understand how people deal with violent deaths and the culture of fear it engenders. Being a Manipuri, I was considered an insider; however, trust/mistrust became one of the central issues I had to deal with. In negotiating trust, I had firstly to rethink the terminologies employed in the field. Terms such as “informants” and “collaborators” are problematic to employ. Eschewing terms that evoke pejorative meanings of being agents of the state’s military apparatus is the first step to negotiating trust. Secondly, there is a general resistance to research investigation. It is felt that research tools fail to capture the historicity of violence and end up reproducing the colonial ethnographic representation of people as inherently hostile and suspicious of each other and of those outside the community. On the one hand, “outsider” research must foray into such fields as the question of complicity, even if one does not actively consent to the project of state violence. On the other hand, since the field fosters mutual suspicion, access to the field is inevitably mediated by one’s identity. As present conditions of the social have been shaped by years of militarization, the adequacy of the tools and methods needs to be questioned. Thirdly, as a supposedly “insider” researcher, I found access to the field more fraught as people categorize kin, friends, and institutions in terms of affinity to either the state or the non-state. Most discussions on field and methods grapples with how to discern whether “informants” are telling the truth. However, in such field sites, the researcher is in a position of reverse gaze; that is, the question of truth, falsification, and trustworthiness – usually applied to the field – now come to bear on the researcher.

The necessity of an interdisciplinary approach

To negotiate access and expand the “field,” I took an interdisciplinary approach, supplementing field narratives by incorporating poetry written between 1980 and 2010. In 1980, AFSPA was extended to the whole of Manipur. I used the poetry of the period to understand how the culture of fear is reflected in poetry (other cultural artefacts, such as songs, fiction, novellas are also viable sources that can be explored). For example, I used Thangjam Ibopishak’s satirical poem “I want to be killed by an Indian bullet.” In this poem, five elements – fire, water, air, earth, sky – come to kill the poet at his home, without any plausible reason apart from the explanation that it was their mission to kill men. The poet requests them to kill him with a bullet made in India. He escapes with his life as they cannot grant him his wish. I analyze the five elements as signifying the anonymity of death squads (to reiterate, it is impossible to attribute violence to the state or the non-state) who pick up their victims or gun them down in their own homes. The lack of a plausible reason to kill implies that one’s death or being spared one’s life (as in the poet’s case) are absurd, arbitrary decisions. The poet’s request is a mockery of the nation-state whose claim to bestow the constitutional right to life rings hollow; it expresses anger against the militarization whereby violence intrudes into the domestic.

Such poems make reflections on death accessible in a context where field narratives can be life threatening. This does not mean that anthropologists should discard ethnography for poetry; what I am suggesting are ways to inquire into violence in the absence of tangible evidence. Researchers need to be cautious of methodological hybridity; however, when ethnography itself has been reformulated as a literary genre, there is no reason not to incorporate poetry as a genre that captures the experience of violence that “objective” field accounts fail to elicit. Poetry resists erasures by creating social knowledge that exists alongside facts of the field. Social anthropology thereby needs to examine its research tools, expand its sources, and learn from other disciplines to retain its criticality in sites of state-engendered violence.

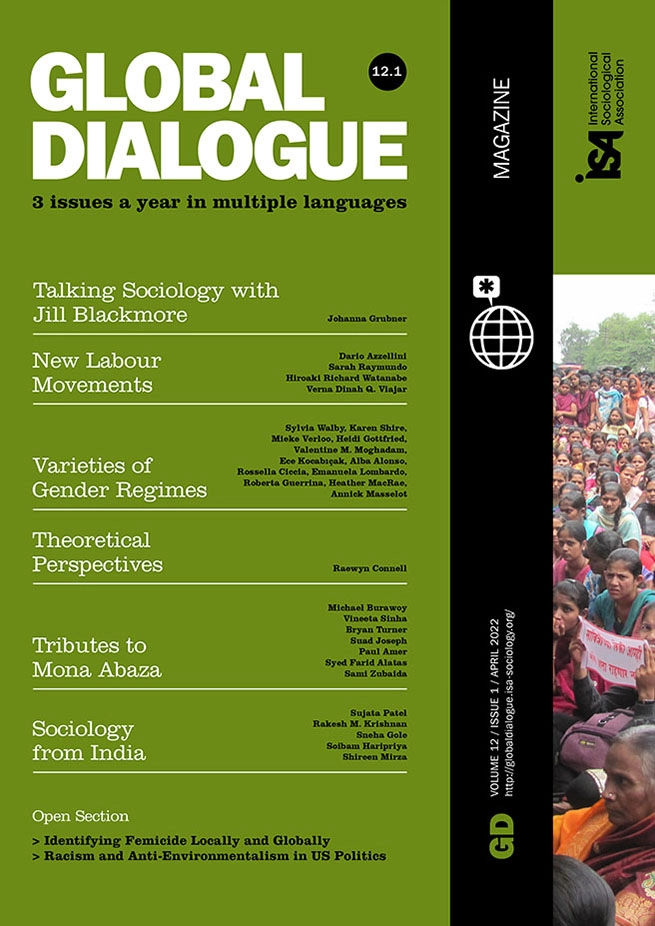

Soibam Haripriya, independent research scholar, India, <priya.soibam@gmail.com>