Forensic Colonialism

March 01, 2024

Critical scholars like Troy Duster, Duana Fullwiley and Amade M’charek have demonstrated that racial concepts have pervaded forensic genetics research, development, and implementation. Adding to these debates, my new book Forensic Colonialism: Genetics and the Capture of Indigenous Peoples (McGill-Queens 2023) shows how influential scientists, first in the USA, then in the European Union and China, have variously used Indigenous peoples as resources and targets of new technologies such as ancestry inference and phenotype (visible appearance) inference, particularly the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. The scientific assemblages (networks) of scientists, universities, security agencies and private companies that are involved are organized mainly through shared narratives about how to hunt criminals and terrorists more effectively in the name of The People and/or Humanity.

A central case study involves how Kenneth Kidd of Yale University has used the Karitiana and Surui of western Brazil and other Indigenous peoples as what he repeatedly terms “resources” for over 30 years. In response to near genocides during Brazilian settler colonization, these peoples adopted close intermarriage to recover their numbers and are genetically interrelated. They were controversially sampled in 1987. In the early 1990s, during the “DNA Wars,” heated public debates between leading genetic researchers like Richard Lewontin and Kenneth Kidd took place over the introduction of forensic genetic testing as evidence in US and Canadian courts. During a 1990 Hells Angels murder case in Ohio, defence lawyers gained access to Kenneth Kidd’s data on the Karitiana and Surui; they and other defence lawyers, including those for a Canadian serial killer, then tried to use it to raise doubts about prosecution genetic random match probabilities that linked defendants to crime scenes. Prominent scientists argued in court testimony, conferences, scientific journal articles, and the US mass media over the significance of the data related to Karitiana and Surui Indigenous peoples and whether or not it meant there might be differences in genetic marker frequencies in racially defined populations in North America.

Post-9/11 expansion

Since the 9/11 attacks, the rapid growth in security spending in the US, the European Union, and China has driven the expansion of forensic genetics, including the development of ancestry inference and phenotype (visible appearance) inference. Before the attacks, research into ancestry and phenotype was considered prohibitively racially controversial. In 2003-4, citing problems with efforts to identify 9/11 victims, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) began extensive funding for ancestry and phenotype as “alternative genetic markers”. The Kidd Lab received US$8.5 million of this funding to develop ancestry inference and individual identification SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) marker panels. This included Kidd and his colleagues stating in a 2011 DOJ funding report that they used the Karitiana and Surui, as well as other Indigenous peoples like Mbuti and Nasioi, as examples of genetic differences to improve the robustness and generalizability of the technologies: “We have deliberately included several small isolated and inbred populations from different geographic regions in our studies.”

By 2015, the marker panels were included in US-made commercial forensic genetic analysis systems. These commercial systems were tested on Indigenous subjects like the Illumina FGx tested on Yavapai Indigenous people of Arizona USA, sampled before the early 1990s. Chinese security agencies tested the Thermo Fisher Ion Torrent system on Uyghurs, and some results were presented at ThermoFisher conferences in 2016 and 2017 during the Chinese government’s increasing repression in Xinjiang.

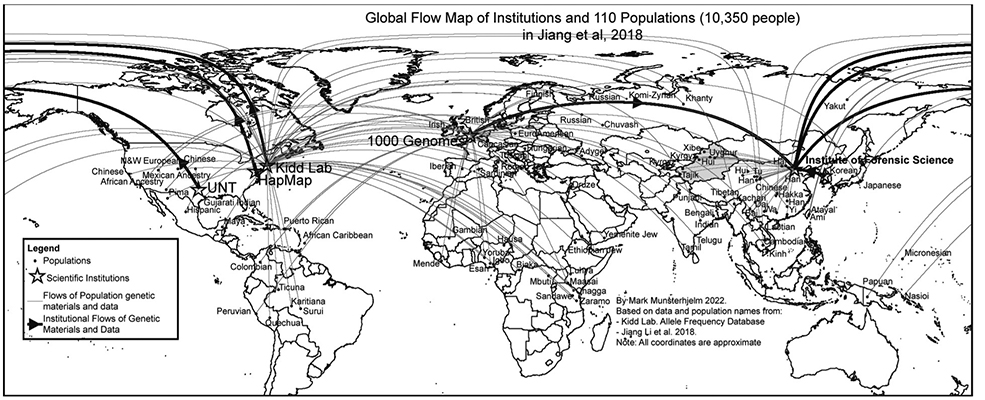

After 9/11, through replacing old labels like “counterrevolutionary”, the Chinese government adopted the global war on terror rhetoric, casting China as a victim of Islamic terrorism during the escalating settler colonization of the strategically important Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Reflecting escalating repression in the early 2010s, the Chinese Ministry of Public Security Institute of Forensic Science cooperated with Kenneth Kidd to develop its ancestry inference SNP marker panels that sought to differentiate between Han Chinese, Tibetans, and Uyghurs. This cooperation allowed Kidd to test his panel of 55 ancestry markers on Chinese subjects in 2015. In return, he provided DNA extract samples grown from cell lines in the Kidd Lab, eventually totalling 2266 samples representing 46 populations (including the Karitiana and Surui). The Institute of Forensic Science use these in developing their own ancestry inference SNP markers, like a 2018 paper by Jiang et al. that used 10,350 samples representing 110 populations, including 957 Uyghurs (a major oversampling). Since the early 2010s, the Institute of Forensic Science has received 8 Chinese patents (and three applications) concerning ancestry inference markers, with some directly targeting Uyghurs and/or Tibetans (e.g. CN103146820B and CN107419017B).

This growing security focus on Uyghurs was also reflected in the Institute of Forensic Science’s joint research with the Beijing Institute of Genomics and the Chinese Academy of Sciences-Max Planck Society Partner Institute of Computational Biology in Shanghai to develop phenotyping technologies targeting Uyghurs in a series of studies involving hundreds of Uyghur subjects published between 2017 and 2019. Scientists from the Beijing Institute of Genomics and the Partner Institute of Computational Biology in turn cooperated with the Visible Genetic Traits Consortium, which involved large numbers of European (e.g. TwinsUK), Australian and Latin American subjects. One 2018 article by Liu et al. included nearly 29,000 subjects, including some 700 Uyghurs.

The above research assemblages have been partially disrupted. Since 2017, there has been increasing international condemnation of China’s crimes against humanity in Xinjiang, including mass incarceration in reeducation camps, repression of religion, culture, and language, and mass biometric and genetic profiling. This growing condemnation finally disrupted genetic research when it was the subject of international coverage in Human Rights Watch reports and Western media outlets. In 2019, Thermo Fisher announced it would stop selling human identification products in Xinjiang. In 2020, reflecting growing US–China tensions, the US Department of Commerce imposed sanctions on the Institute of Forensic Science, which the Chinese government has protested against as interference in its internal affairs and a weakening of global cooperation against terrorism. The reactions of some Western and Chinese scientists who are involved have included dissociating themselves from further research and denials of wrongdoing.

These influential forensic genetic assemblages have been involved in mass violations of rights, including routine unauthorized secondary usage of samples taken decades ago, which violates contemporary ethical norms and Indigenous sovereignty and rights (e.g. Article 31 of the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples). The failures to limit research on vulnerable populations have been exemplified in scientific cooperation with Chinese state security agencies on Uyghurs and other Xinjiang peoples. In conclusion, the pervasiveness of racially configured concepts and hierarchies in forensic genetics requires further inquiry and public debate.

Mark Munsterhjelm, University of Windsor, Canada <markmun@uwindsor.ca>