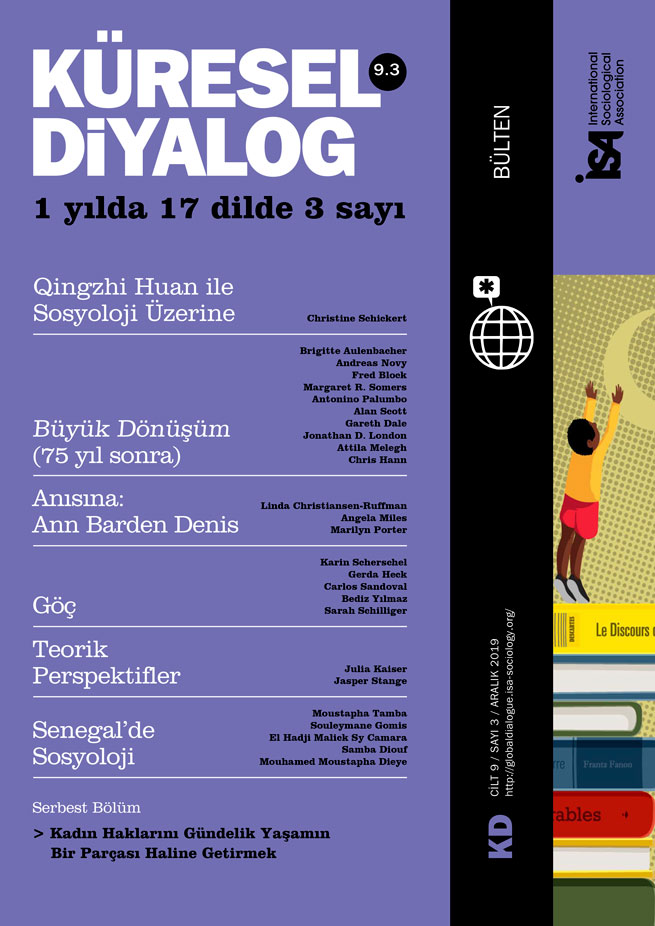

For an Eco-Socialist Vision: An Interview with Qingzhi Huan

November 11, 2019

Qingzhi Huan is professor of comparative politics at Peking University in China. In 2002-3 he was a Harvard-Yenching Visiting Scholar at Harvard University, USA and in 2005-6 Humboldt Research Fellow at the University of Mannheim in Germany. His research focusses on environmental politics, European politics as well as left politics. He authored and edited a number of books on these issues including A Comparative Study on European Green Parties in 2000 and Eco-socialism as Politics. Rebuilding the Basis of Our Modern Civilisation in 2010.

He is interviewed by Christine Schickert, the administrative director of the Research Group on Post-Growth Societies at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Germany and assistant editor of Global Dialogue.

CS: Climate change has become one of the most talked about political issues in recent years, at least in the countries of the Global North. Could you describe the role this discussion plays in Chinese politics and society today?

QH: Dealing with global climate change as one of the major issues of international environmental politics has traveled quite a long way since the signing of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change(UNFCCC) at the Rio summit in 1992. Generally speaking, like most of the other developing countries, China’s position on combating climate change is clear and coherent – it is called the “Principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibility” (CBDR): First of all, climate change is a common challenge or crisis for the whole of human society rather than just for advanced or developing countries; secondly, the so-called advanced countries or regions, especially the EU and the US, should take on their main historical responsibilities by offering or transferring necessary resources and technologies to the developing countries; thirdly, developing countries, including China, should make increasing contributions to global climate change control and adaptation in accordance with their growing capacities.

Based on this policy position, China’s participation in international climate change politics over the past years can be divided into three stages: pre-1992, 1992-2012, 2012-now. Up until 2012, the dominant understanding was that it was the advanced countries like the EU countries and the US which were to take immediate actions. Since 2012, the Chinese government gradually updated or shifted its position towards international cooperation on climate change, especially under the framework of the UNFCCC. The best example here is the new role of China in reaching and implementing the Paris Agreement.

To be honest, the major impetus for this adjustment of the Chinese policy position does not stem from the signing and implementation of the Paris Agreement but comes from implementing the national strategy of promoting the construction of an eco-civilization. Briefly speaking, marked by the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the modernization of “national ecological environment governance system and governance capacity” has been recognized as one of the top political and policy goals for the CPC and the Chinese government, and joining international cooperation on climate change more actively is one ideal symbolic case to show their political willingness. For instance, China is also paying more and more attention to the implementation of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) by organizing several important, related international activities in 2019-20.

CS: Environmental protection is not a new issue in China. In 1972, China, unlike other countries ruled by socialist parties, took part in the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, where a number of principles and recommendations concerning environmental protection were agreed upon. Could you sketch developments and changes in China’s environmental policies since then?

QH: It is true that China’s environmental protection as a public policy formally started in 1972, when the Chinese delegation attended the Stockholm Conference on Human Environment. As a result, in 1973, China held its first national conference on environmental protection and set up a national office in charge of this policy issue. Since then, China’s environmental policy has experienced at least four stages of development: 1973-89, 1989-92, 1992-2012, and 2012-now.

In the first stage, with the formation and implementation of the “reform and opening-up” policy in 1978 under the political leadership of Deng Xiaoping, environmental protection quickly became a prominent policy issue, and consequently, “environment protection as a basic state policy” was officially recognized in 1983 and has been one of the key policy guidelines for China’s environmental protection until today. During the second stage, under the political leadership of Jiang Zemin, sustainable development became the major expression of the CPC and Chinese government’s political ecology and environmental governance strategy. From 2002 to 2012 – a transition stage in more than one way – under the political leadership of Hu Jintao, the concept of the “two-pattern society construction” (resource-saving and environmentally friendly society), put forward in 2005, was the CPC and Chinese government’s central term of that time. In 2007, the term “eco-civilization construction” was included in the working report of the 17th National Congress of the CPC. Since 2012, the real change is not that “eco-civilization construction” has become the umbrella word of the CPC and Chinese government’s political ecology and environmental governance strategy, but rather that environmental protection and governance are recognized as an integral part of the pursued “socialist modernization with Chinese characteristics in a new era,” theoretically and practically.

CS: For quite some time now, your work has focused on the idea of eco-socialism. You argue that “greening” capitalism is not the answer to the current ecological crisis but neither is “greening” traditional socialism. Could you elaborate on this argument and explain what eco-socialism means?

QH: Briefly speaking, eco-socialism as a green political philosophy includes two major aspects. On the one hand, it argues that ecological and environmental challenges on the local, national, and global level, especially under the dominant institutional framework of contemporary capitalism, are not just partial or temporary problems or defects, but are inseparable from the framework itself: they follow the logic of capital proliferation and the protection of the interests of capital-owners. In this sense, various measures under the capitalist regime, the so-called “green capitalism” or “eco-capitalism,” cannot solve environmental problems. Of course, as Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen have expounded clearly in their book The Limits to Capitalist Nature this does not mean that capitalist measures against environmental damage, or even “green capitalism,” are totally impossible in reality (though always implemented in a selective way).

On the other hand, what is stressed in eco-socialism as a political philosophy is that it is a new type of socialism, or an updated version of socialism, and thus different from a simplified or falsified greening of traditional socialism. It is worth noting that the scientific socialism or communism that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels suggested nearly two centuries ago is an ideal which has so far not been realized, whether in the former Soviet Union or in today’s China. And this ideal cannot be established in any country or region of the world in the foreseeable future. This implies that what we are imagining or striving for is an eco-socialist orientation of our contemporary world rather than a totally new socialist society. In other words, one of the main tasks for eco-socialists today is to make clear why various measures under the capitalist regime will eventually fail to solve the problems that they claim to solve, and why various initiatives of eco-socialism as real or radical alternatives can indeed bring about substantial change in all societies, so that “another world is really possible.”

CS: In many discourses that I have followed, eco-socialism is discussed as an alternative to green capitalism with its own vision of the future that not only offers solutions for the ecological crisis but also addresses issues of inequality; it aims at connecting environmental justice with social justice. But you argue that eco-socialist concepts at the moment don’t seem attractive to people. Why is that?

QH: Admittedly, the concept of eco-socialism is still not as popular as many people may expect or argue, not only in capitalist countries but also in socialist countries including China. In my opinion, there are various reasons for explaining this anomaly. Firstly, eco-socialism as a political ideology and public policy is still very much affected by the stained reputation of traditional socialism in the former Soviet Union and Eastern European countries, which were obviously unsuccessful in institutionalizing the socialist ideas and values and in dealing with environmental issues, as Saral Sarkar has convincingly analyzed in his book Eco-socialism or Eco-capitalism? Moreover, the hegemony of neoliberalism throughout the world after the collapse of the socialist bloc in the early 1990s and its political and ideological propaganda have undoubtedly been a success, making the majority of people believe that there is indeed no alternative to capitalism. Most interestingly and/or regrettably, the economic and financial crisis of 2008 in Europe and the US also did not substantially improve the structural situation for radical or alternative politics, including eco-socialism. The rise and growing popularity of “green capitalism” or “eco-capitalism” in recent years can be considered as supporting evidence for this argument.

Secondly, as far as China is concerned, the competing political and policy interpretation of “eco-civilization construction” and “socialist eco-civilization construction” is a good example to illuminate that eco-socialism is far from being an established political ideology and political ecology. One deep divergence is whether or not a socialist orientation or direction is an institutional precondition for modernizing the environmental protection and governance system of today’s China. From an eco-Marxist perspective, over-emphasizing the introduction of the so-called modern institutions or mechanisms for environmental protection and governance from the US and the EU would be at the risk of neglecting the socialist reshaping of the whole society which is essential for a future socialist eco-civilization.

CS: What is needed to make eco-socialism more attractive as a vision for a future society?

QH: Needless to say, this is an urgent and very challenging task for eco-socialists today. First of all, socialist/green-Left political parties and politics are still the major forces to make the eco-socialist vision for a future society more desirable and attractive among the public, and lots of work can be done by them. For instance, an encouraging message from the European Parliamentary elections of 2019 is that the European electorate, especially the young generation, are holding quite a supportive position towards combating climate change and other global environmental issues, but the Left as a whole did not benefit too much from it. Secondly, international dialogue and collaboration among academics on all issues relating to eco-socialism should be further strengthened. Of course, it should be a more equal and open-minded, two-way process between the West and the developing countries. To be frank, China has been a “good” student of the West over the past decades in the sense of doing its best to imitate what the advanced nations have done or are doing to modernize the country. From now on though, China needs to be a more independent and reflective partner of the international academic community, focusing on how to really make the country better. Thirdly, one of the key tasks to make eco-socialism more attractive, especially in China, is to make “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in a New Era” more attractive. From my point of view, a crucial way is to consciously introduce and implement the principle and policy of “socialist eco-civilization construction.”

CS: You distinguish between “growing economy” and “growth economy,” the latter being dependent on continued economic growth, something that seems detrimental to solving the ecological crisis. What does this distinction mean in regard to China?

QH: I used the term “growing economy” in 2008 to conceptualize the nature of economic development in China at that time, to show how I somewhat differ from Takis Fotopoulos, a London-based Greek thinker, who analyzed whether sustainable development is compatible with globalization by looking at developments in China. My major argument is as follows: both in terms of the legitimacy, desirability, and sustainability of resource support and environmental capacity, the economic growth rate of China at the beginning of the 21st century was to a large extent necessary or defendable. Of course, the overall situation of China’s economic development has changed dramatically over the past decade and is currently facing an even more challenging situation today owing to the trade dispute/war with the US.

The real question in this regard is whether or not the Chinese economy is gradually moving towards a growth economy as Takis Fotopoulos has defined it. My reflection is that there is still no simple answer to this question. On the one hand, the annual economic growth rate of 6-7% since 2015 is almost half what it was ten years ago (11.4% in 2005), indicating that China is continuously optimizing its economy in line with the different stages of development, and, at least for the central and western regions of China, that an appropriate economic growth rate is still necessary or maintainable in the near future. On the other hand, considering the economic aggregate of China today – according to the World Bank, it is 13.608 trillion US dollars in total and 15.86% of the whole world in 2018 – even an annual growth rate of around 5% may bring about wide and tremendous impacts on our ecological environment. This is the very reason why we argue that an eco-socialist perspective or “socialist eco-civilization construction” has the potential to make a contribution to better combine the necessity of meeting the basic needs of common people and protecting the ecological environment: more ecologism and more socialism.

CS: In European countries and in North America, the idea of a green capitalism is the mainstream answer to the current ecological challenges. What could they gain from alternative visions of the future like the one you put forward?

QH: Arguably, “green capitalism” or “eco-capitalism” is the most practical or even “rational” approach to deal with the current ecological challenges in European countries and in North America, because, thanks to the hierarchical international economic and political order and the increasingly wide acceptance of the “imperial mode of living” in developing countries, these “advanced” countries can manage to use the global resources and sinks to their own advantage. If such a structural configuration remains unchanged, one can imagine that there will be little possibility for the world to move towards an eco-socialist future.

However, it seems that this configuration has indeed become socially and ecologically problematic in recent years. On the one hand, following the economic rise of several major developing countries including China, it is becoming more and more difficult for the US and European countries to maintain the status quo of the international order, which will threaten not only their position of hegemony in the traditional sense but also their green model of “eco-capitalism.” In other words, there will be less and less space or possibilities in reality for these “advanced” countries to maintain the good quality of their local environment while continuing to enjoy a high level of material consumption. To some extent, the increasing tensions today between China and the West led by the US can be interpreted in this way. On the other hand, more and more developing countries, especially the emerging economies like China, are taking the ecological environment problems seriously for different reasons. This implies that there will be more and stricter restrictions from developing countries on the acceptance of “dirty” capital and technology, let alone of waste and garbage, as the dispute over waste import between the Philippines and Canada has clearly shown.

In both senses mentioned above, in my opinion, the principles and ways of thinking of eco-socialism can contribute in making European and North American countries eventually realize the limits and defects of “green capitalism” or “eco-capitalism.” Solving local or short-term problems while others pay the costs needs to end, and a process of radical social-ecological transformation needs to be initiated as soon as possible. A more just world and more equal society are the precondition for a cleaner environment.

Qingzhi Huan <qzhuan@sdu.edu.cn>