Read more about Uprising in the Ukraine

The Revolution Has Not Even Begun

by Volodymyr Ishchenko

May 16, 2014

“Maidan” is a unique sociological phenomenon. Such terms as “mob,” “meeting,” or “demonstration” do not adequately capture its dynamic character. Technically “Maidan” refers to Independence Square in Kyiv, but it is now indelibly linked to a constantly changing encampment that includes both a tent city and several adjacent buildings occupied by the protestors. The dynamism and drama of the Euromaidan can be broken into four phases.

Phase One: Protests Begin

Ukraine and the European Union had planned to sign an Agreement of Association on November 28-29 (2013) at the “Eastern Partnership” summit in Vilnius. However, much to the surprise of the Ukrainian population, the Ukrainian authorities suspended preparations for signing the agreement. The first Maidan meeting took place on November 24, bringing together between 50 and 100 thousand people – the largest gathering since the Orange Revolution of 2004. Supporters of the EU began to erect tents in Independence Square and hundreds stayed there overnight. Since “Maidan” means “a square” in Ukrainian, the following rallies and the permanent tent-city were called “Euromaidan.”

Phase Two: The Assault on the Protestors and their Changing Profile

At 4 am on November 30, several hundred members of the special branch of the police, “Berkut” [Golden Eagle], used force to disperse supporters of European integration, mainly young people meeting on the Maidan. It was more than a mere expulsion from the square – the protestors were kicked and clubbed and then pursued along the Khreschatyk (main street) and connecting streets as far as St. Michael’s Cathedral where monks opened the gates and hid the fleeing students.

These events caused a public outcry. Accordingly, the following Sunday (December 8) a record crowd of protestors, estimated to between 700 thousand and a million people, arrived at the Maidan and its surrounding streets, coming not just from Kyiv but also from the surrounding, mainly Western, regions. Who came to the Maidan and what demands did they have? The Foundation Democratic Initiatives commissioned a survey of the protestors, conducted by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) during the weekend of December 7 and 8. We did 1,037 face-to-face interviews. The follow-up survey was conducted on December 20, which was a weekday, and included only the occupants of the Maidan encampment.

It is necessary to say a few words about the methodology we used. We quickly learned that our experience in exit polls and street interviews was not of much use in this constantly changing context where the number of permanent Maidan inhabitants fluctuated between 5 and 20 thousand but could rise to a 100 thousand on a Sunday rally. Therefore, our usual methodology designed for a stationary context required modifications. Our sampling technique identified sectors of the Maidan (including the occupied buildings), and we randomly selected interviewees within each, weighting the results by the estimated numbers in each sector. With regard to the occupants of buildings the standard exit poll procedure was used, i.e. interviewing those who exit the building at given intervals. As for the Maidan, we demarcated several interview points on the square. Alongside the interviewer a three-meter line was drawn and everyone who crossed this line was to be interviewed. However, in practice the lines were not visible so the interviewers created an imaginary line between them and a prominent object. Supervisors observed the interviews as they took place and each interview location was photographed from above to estimate the number of people in the specific sector, so as to be able to weight the results.

The two leading motives that drove people to Maidan were: the brutal beating of Maidan demonstrators during the night of November 30 (70%) and Yanukovych’s refusal to sign the Association Agreement with the European Union (54%). Other motives for participation in the protests included the desire to improve life in Ukraine (50%) and to change the power structure of the country (39%). Maidan respondents made the following demands: to release the arrested protestors and stop the repression (82%); the resignation of the government (80%); the resignation of Yanukovych followed by early presidential elections (75%); to sign the Association Agreement with the EU (71%); to commence criminal investigation and prosecution of those responsible for violence perpetrated against Maidan protestors (58%). In short, we can say that the main demands focused on issues of social justice and human dignity, which is why journalists called the protests, “The Revolution of Respect.”

Comparing the permanent Maidan encampment with the Maidan rallies, there was a clear dominance of people from outside Kyiv in the former (81%) whereas the latter were dominated by Kyiv residents (57%). Among non-residents, protestors from Western Ukraine dominated both Maidans (52% at the rallies and 42% of the encampment), indicating a slightly higher proportion from other regions in the encampment. The educational level at the rallies was very high: those with college education accounted for 64% while incomplete college education accounted for another 13%. As regards occupation, almost 60% were professionals, entrepreneurs, and managers. In other words most of the participants attending the rallies were from the middle classes. At the encampment, however, the proportion of professionals was less than half that of the rallies and the holders of college degrees comprised less than 50% of occupants.

Phase Three: The Radicalization of Maidan

Maidan endured week after week, but its demands were not heeded and activists were continually arrested. The protestors – living in tents at temperatures of 10 degrees below zero –became more radical. On January 16, Parliament passed very tough laws that significantly increased penalties for protest (journalists called them “dictatorial”). Outraged by these laws, protestors organized a march from Maidan to Parliament which was stopped by the police. In the course of fights around the barricades erected on Grushevskovo Street, many were wounded and several people were killed. In addition, unknown infiltrators abducted protestors to the forests where they were brutally beaten. One activist was found dead and several went missing.

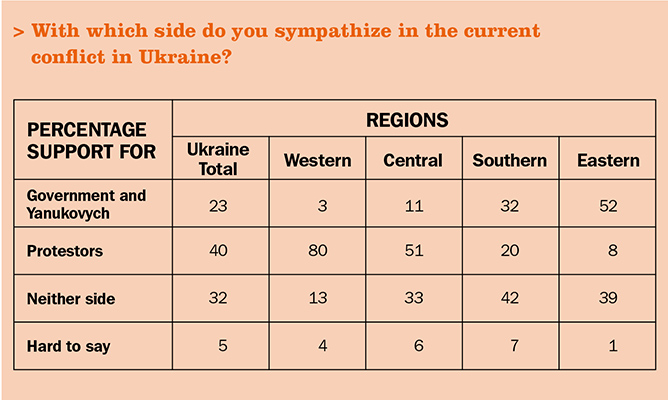

On February 3, together with Democratic Initiatives, KIIS replicated the survey of Maidan (the previous one having been conducted on December 20). During these one-and-a-half months Maidan camp was transformed into a military camp: “Maidan Sich” (“sich” refers to a camp of Zaporozhian Cossacks who are a symbol of Ukrainian independence). The proportion ready to resort to more militant forms of protest increased: those in favor of picketing government buildings increased from 38% to 56%; those in favor of seizing the buildings increased from 19% to 41%; those in favor of creating parallel power structures and military formations increased from 31 to 50%. National opinion polls and daily news pointed to the radicalization of attitudes in the entire country. Attitudes toward Maidan varied by region. A survey conducted by KIIS between February 8 and February 18 in all regions of Ukraine including Crimea (2,032 face-to-face interviews) showed that in the country as a whole 40% of the population supported Maidan, but that this varied from 8% in the East to 80% in the West.

Phase Four: Violent Repression and Victory for Maidan

On February 18, the situation escalated as preparations to storm Maidan were under way. Maidan was surrounded by the police, snipers moved into the occupied buildings, and clashes began, which continued day and night with only short interruptions on February 19 and 20. Assault weapons were used on both sides. During these three days more than 100 protestors were killed or died from wounds along with five police officers from the Berkut. In addition, more than 1,500 people were injured, and about a further 300 disappeared without trace. This was a trauma for the country. In the Parliamentary Session of February 21, a number of members of the ruling party supported the opposition and Parliament voted to call off all the militias and send them back to their barracks.

At the same time, in the presence of representatives from Poland, Germany, France and Russia, President Yanukovych signed an agreement with the opposition to settle the crisis. However, in the evening of the same day he suddenly disappeared. Attempts were made to intercept and apprehend him but he managed to escape to Russia. So Parliament appointed a new government, announced new elections for President and, following the Constitution, the Speaker temporarily assumed the position of President. In this way power changed hands in the Ukraine.

(Received March 9, 2014)

Volodymyr Paniotto, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, General Director, Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), and member of ISA Research Committee on Logic and Methodology (RC33)

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: