Read more about From Lebanon

The Shifting Sands of Sectarianism in Lebanon

by Rima Majed

December 12, 2014

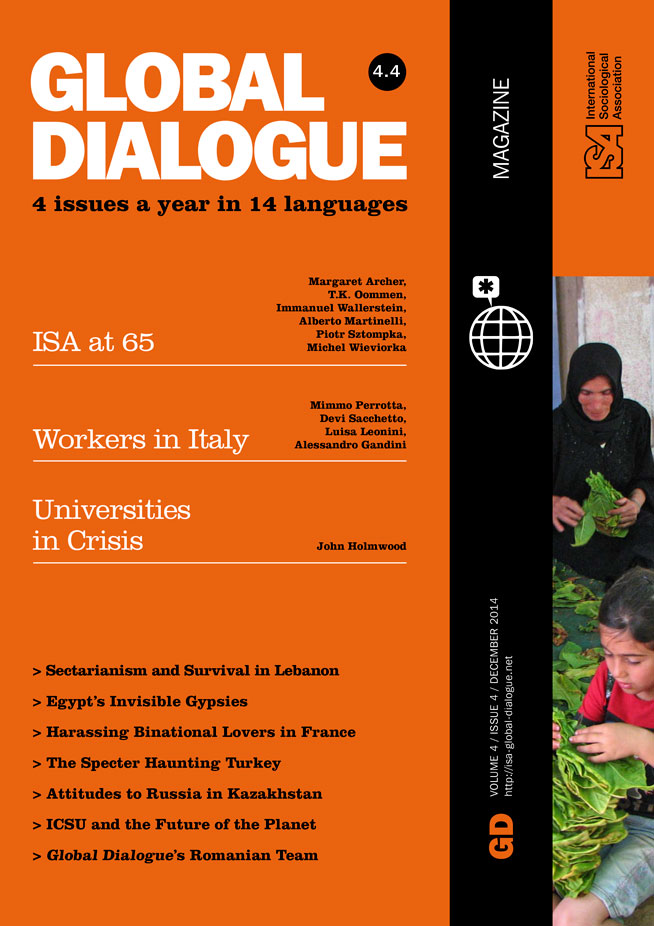

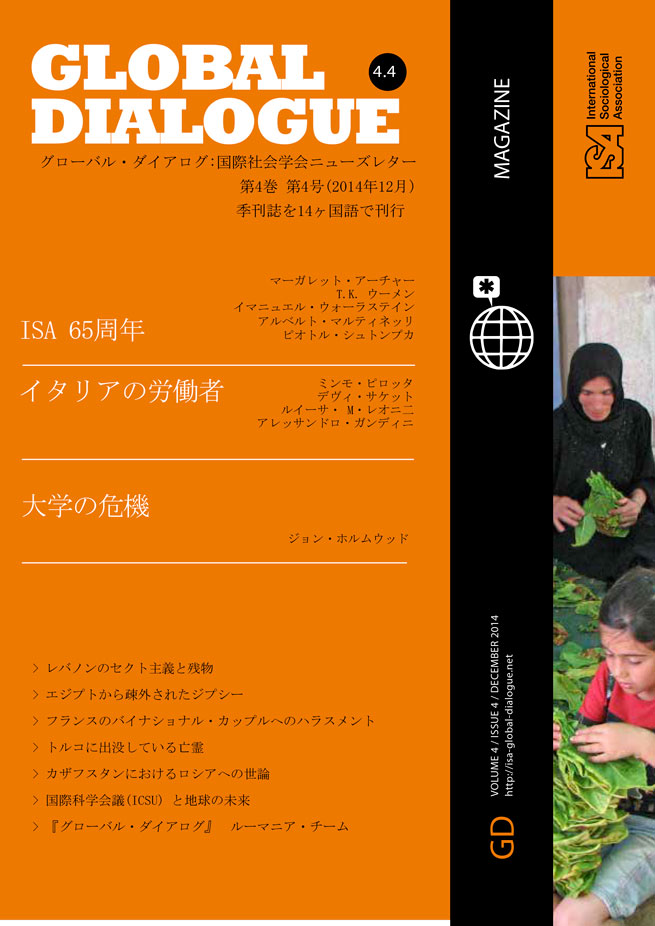

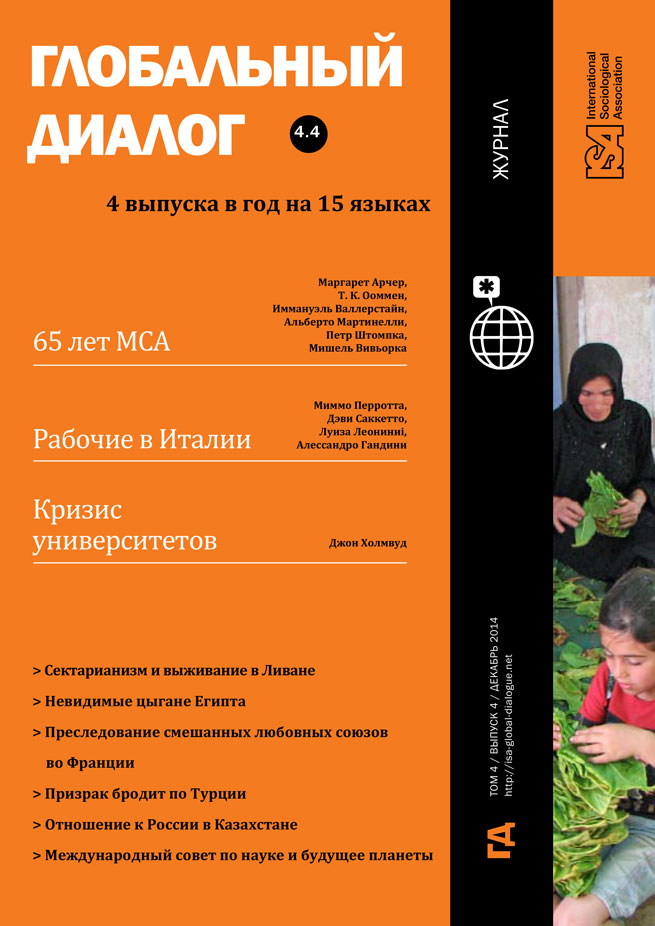

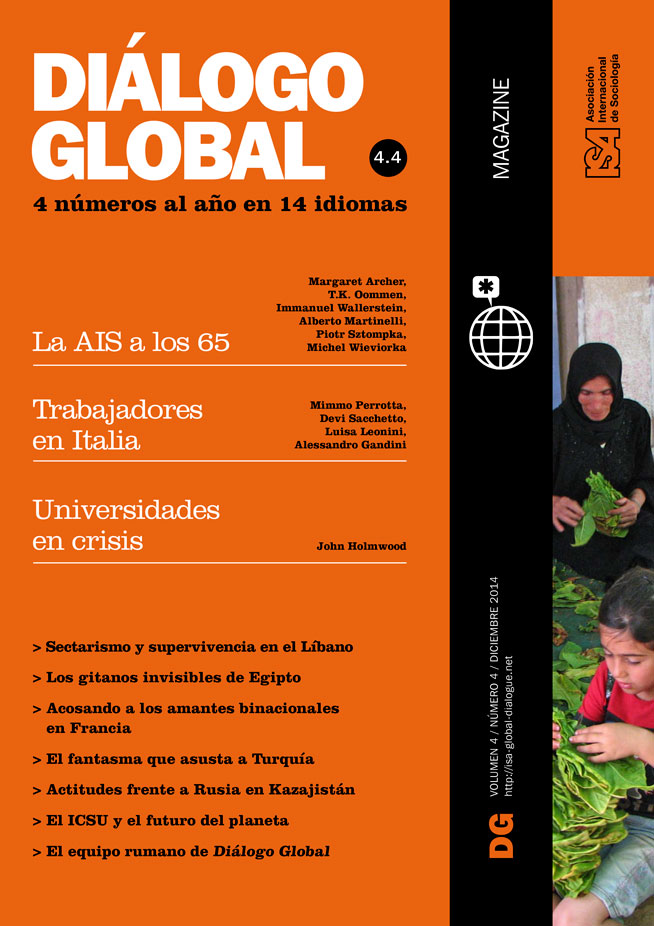

There is so much violent rupture going on in the Arab world – in particular in that roiling corner of the Eastern Mediterranean where the wars in Syria and Iraq continue to rage, radiating outwards – that it is hard, if not impossible, to notice the more continuous rhythms and practices that prosaically continue, the cycle of activities that undergird the daily fight for life in inhospitable, if not impossible, settings. One of those remarkably dependable cycles is this year’s tobacco crop, already coating the hills of South Lebanon in electric green, heralding high summer. The months of June, July, and August is tobacco season in the arid highlands of South Lebanon, and has been for centuries. Through repeated seasons of rupture the tobacco harvest has sustained the resilient inhabitants of these difficult margins.

Called “the bitter crop,” tobacco is cultivated by homesteads across the hills of South Lebanon for the state-owned monopoly Régie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs, better known to those who doggedly serve it as the Régie. Yes, tobacco is a vile, labor-intensive, carcinogenic, exploitative market commodity; environmental or humanitarian outfits roll through South Lebanon touting replacement crops like thyme, or installing emblematic and quickly abandoned infrastructure like water-harvesting pools for “alternative” forms of agriculture. But the inhabitants of Lebanon’s southern marches will not let tobacco go. To them, it is synonymous with life: the income it ensures cannot be forgone in a context of so much existential insecurity. It is a (bitter) lifeline that has seen the inhabitants of this oft-violated border zone through years of conflict, invasions, occupations, neglect and grinding structural violence.

Today, tobacco is booming. Since South Lebanon’s last cycle of war in 2006 (locally referred to as the “July War”), tobacco has seen unprecedented growth – despite the fact that in the final hours of that vicious, month-long offensive, the Israeli Air Force dropped millions of cluster bombs across South Lebanon, in an act of war against the landscape that is lifeline and livelihood. That year’s crop was scorched, ruined, and withered on the stalk. But even in the wake of this devastation, Lebanon’s southerners returned full force to cultivate a steadfast crop.

Today, tobacco fields sweep across the South, uprooting ancient olive and citrus groves, replacing subsistence agriculture with growing dependence on market-bought goods (because “tobacco cannot be eaten”). In a landscape peppered with land mines, cluster bombs, military infrastructure and no-go zones, tobacco is also overtaking livestock who need to be herded across increasingly militarized terrain. The South leans ever more on a crop and commodity that is increasingly marginalized and maligned, restricted and regulated on the global market.

Tobacco is a hardy weed that flourishes in arid highlands. Through its brief life (February – April as seedling, May to August as a field crop) it feeds off the dew of dawn, needing no irrigation. It is even more versatile as a crop in an impoverished rural area, as it requires no additional infrastructure or space: half-built (or half-destroyed) homes, front and back gardens, hillside terraces, irregular, often rocky plots of land. It has a readily available workforce: the women, children and elderly inhabitants of the homesteads of the “frontline villages,” where able-bodied males work abroad or in Lebanon’s cities. The residual population of these largely depopulated villages labor intensively on the crop that assures at least a supplemental family income, year after year.

Only those who hold licenses – which are limited in number and highly valued – may cultivate or sell tobacco. Prior to labor activism around tobacco in the 1960s and 70s, tobacco licenses were concentrated in the hands of the all-powerful landlords who owned most of the land. Today’s small farmers are descended from the sharecroppers who once worked the land. As guerrilla warfare in Lebanon’s southern borderland heated up in the 1960s and 70s, many landlords left for the cities; “their” peasants, who remained behind on the land, used remittances from a network of migrants in Africa, Latin America, Australia and elsewhere to buy small plots of land, eventually also acquiring tobacco licenses. Many peasants stuck around through invasions, a 22-year Israeli occupation of the border strip, the subsequent post-occupation era and the 2006 war. Through it all they farmed tobacco gaining a semblance of control over tobacco production by wresting the licenses away from the powerful.

What accounts for the success of tobacco along Lebanon’s southern marches? Why is tobacco, the bitter crop, the stalwart friend of the forgotten, downtrodden poor?

On one level, it is about what works. And who works. The demography and geography as well as South Lebanon’s temporal and spatial rhythms, create an environment where tobacco farming thrives – and with it, a life on the land in an otherwise inhospitable place can continue. On another level, the crop’s success is structured and enabled by the Lebanese state, which barters immense profit on the global tobacco market for a pact packaged as a generous social contract: the state pays a fixed price (8 to 13 USD per kilo) to licensed tobacco farmers, regardless of global price fluctuations.

This contract is both loved and hated by those who farm tobacco: the assured income harnesses them to an exploitative and destructive yet immensely profitable industry. The Lebanese state couches its “tobacco subsidy” in terms of pastoral care for its needy citizens, yet it happily pockets the massive profits it gains from this global trade.

Two narratives emerge about Lebanese tobacco. One narrative revolves around life, labor and love: many successful southerners ascribe their success to the fact that their families were able to farm tobacco, using the money to send them to school. Those who farm the crop – an overwhelming majority of whom are women – speak with pride of their skill in harvesting, sorting, threading, drying and packing the crop. In their eyes their tobacco is “the best in the world.”

Another narrative emerges from those who buy the crop, the officials of the Régie, who speak instead of uneven, even dubious quality. They bemoan having to buy the crop from households across the South – an unreliable commodity, which is re-sorted and repackaged and then stored in warehouses for long spells while the monopoly negotiates deals with global tobacco companies, who are required to buy a percentage of the annual Lebanese tobacco crop in return for an equal share in Lebanon’s commercial tobacco market. Some suggest that much of the laboriously cultivated tobacco of South Lebanon is simply trashed. The stark differences between the two narratives highlight the crop’s controversial nature.

Regardless of its ultimate fate and controversial uses, and because of a dearth of equally reliable alternatives, the cultivation of tobacco remains a lifeline in South Lebanon. The “frontline villages” of the Lebanese borderland are the most avid cultivators of the “bitter crop,” for it is in and through their labor for a market commodity that consistently sells at a stable price, that the villagers of South Lebanon manufacture a form of stability conducive to a marginally successful form of life in a space of constant rupture, destruction and violence.

Munira Khayyat, American University in Cairo, Egypt <mk2275@columbia.edu>

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: