Read more about Bulgaria Yesterday and Today

Tall Tales from Sofia’s Streets

by Martin Petrov

Caught between Two Socialisms

by Mariya Ivancheva

August 17, 2013

As we know from Maurice Halbwachs, social memory is intimately linked with forming collective identities. After 1989, the heated public debates about the fate of the Bulgarian Jewish population during the WWII, tell us much about the way the past can shape the politics of the present. In the 1990s the Holocaust became a major symbolic resource in forging political subjectivities, namely the ability to distinguish between the former communists and the new anticommunists. Both parties shared common post-political utopia for the future: European integration, neoliberalization, democratization, etc. And, as the Bulgarian sociologist Andrey Raitchev has observed, distinctions were projected onto the past. “Was there fascism before socialism?” became the central theme. The anticommunists engaged in conservative historical revisionism. Their main slogan was “45 years [of communism] is enough!” and they claimed that fascism was a communist exaggeration to legitimize the socialist regime and justify its abuses of power. The former communists, on the other hand, often called their opponents revanchists and even fascists, because they papered over the atrocities of fascism. This is an old debate, but it took on Bulgarian characteristics when it became entangled with the fate of the Bulgarian Jewish population – a fate that is subject to conflicting interpretations.

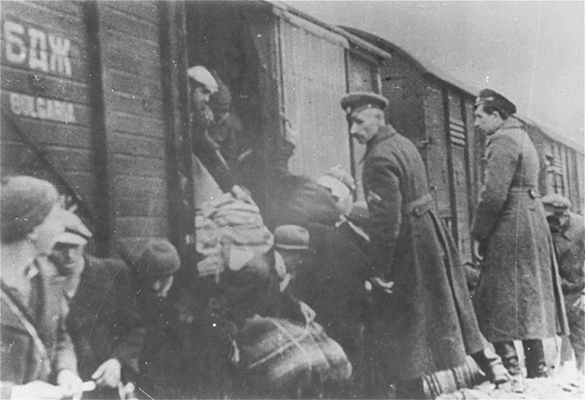

Two Narratives of Bulgaria’s Treatment of Jews

During WWII Bulgaria joined the Axis powers and annexed almost all of current Macedonia, Northern Greece and parts of modern-day Serbia. The Jewish population of the “old” territories of Bulgaria was extremely repressed (stripping away of civil rights, anti-Semitic legislation, dispossession, work camps and so on), but the Final Solution was resisted by both the antifascist militants and segments of the elite, and was averted at the last moment. In the “new” territories, on the other hand, this was not the case and the “foreign” Jewish population was finally deported to Treblinka.

These events fueled both the former communists and the anti-communists with arguments. Sociological research of the party newspapers of the 1990s, conducted by the Institute for Critical Social Studies, shows that the former communists were focusing on the extermination of the Jewish population in the “new” territories to prove the “fascist essence” of the pre-socialist regime. The anticommunists, by contrast, focused on the fact that the Final Solution in the “old” territories was averted, largely due to resistances within the elites. They downplayed the role of the antifascist militants – strong among the communists – often portraying them as “criminal.”

Both narratives shared an inability to recognize the arguments of their opponents as legitimate. The Bulgarian sociologist Lilyana Deyanova dubbed the phenomenon post-communist negationism. Negationism is not limited to the past, but marks the incapacity to acknowledge the very existence of the “other’s” position. It is often accompanied by calls to criminalize the “incorrect” memories of the “other” – nicely fitting in with the wider European concern and the trend of imposing new memory laws. Subjectivities embedded within this mode of social memory see their opponents in an extremely antagonistic way. The political adversary is debunked as radically different – abnormal, unpatriotic, a traitor and a liar, a foreign intruder into the national body. In this “anti” discourse, the nation is thought of as harmonious totality. These stale debates reduce politics to either - or. Were the Jews saved or not? Was Bulgaria democratic or fascist? No other option was there.

After 2001, stable political identifications collapsed along with the two-party model that represented them. As regards the fate of the Jewish population, it was the anticommunist narrative that prevailed. The post-war communist trials were officially deemed illegitimate, including the ones against fascists, collaborators, and executioners. The deportation of Jews from the occupied territories was explained away as “we had no choice,” or “these territories were not truly ours.” Nevertheless, paradoxically, this took place within a discursive framework that tended to praise the territorial expansion as “liberation” and “unification of Greater Bulgaria.” Recent years have witnessed not only the consolidation of that narrative, but its projection onto Macedonia, which is accused, by Bulgarian political and media mainstream, of “falsifying” history. So that the recently built Holocaust museum in Skopje is portrayed as “fake,” “empty,” and so on. It is not just the “communists,” but also the Macedonians who are now seen as the enemy, spreading lies about Bulgaria’s involvement in the Holocaust.

Avoiding the Realities of Fascism

Politics of memory since 1989 have effectively displaced reflection on the specificities of Nazi anti-Semitism and of fascism itself. One simplistic theory of fascism, existing during state socialism and stemming from Dimitrov’s (Bulgaria’s communist leader) classical definition (reducing fascism to its class content), was replaced by another. The Holocaust was reduced to shallow moralism with a slightly chauvinist twist, aimed at telling “us” whether “we” are good or evil. The much needed debate on fascism is avoided by putting the blame on an inexplicable foreign force that imposed its “discrimination and intolerance” but was luckily resisted by the “traditionally tolerant civil society.” The realities of Bulgarian fascism are downplayed by emphasizing fascism’s (lack of) formal characteristics. There was no mass party that called itself fascist – hence no fascism existed. There is almost no reference to the huge literature on fascism, apart from reductionist comparisons of the “two totalitarianisms.” For instance, there is no reference to Zeev Sternhell’s analysis of fascist ideology and its Sorelian desire to go beyond left and right. But what is also missing is fascism’s vitalism, its de-universalization of citizenship, its cult of youth and its activism, the Nazi concept of “Judeo-Bolshevism.” its fascist anti-communism, etc. In short, there is an attempt to avoid any notion of fascism that may invite uneasy parallels with the contemporary post-political utopias. Unfortunately these lacunae are not limited to the political mainstream – they have penetrated deeply the academic world, including many sociologists.

Political and journalistic mainstream glorifies the “Bulgarian heroism” and the wartime “civil society” that “saved the Jewish people in Bulgaria,” superimposing currently popular concepts onto the past. The mainstream is blind to the fact that while indeed there were many who resisted, there was also a strong pro-Nazi “civil society,” including both movements and officials, who resolutely pushed for the strict implementation of the Final Solution. This poses the question of which “civil society” resisted? Whose Bulgaria stopped the deportation? What lies hidden behind the essentializing and ahistorical talk is that there was (and still is) more than one Bulgaria.

Recently, however, there has been a resurgence of critical inquiries and publications into the matter, mostly by historians and sociologists. In late 2012 the largest human rights NGO organized a landmark conference entitled “Know Your Past,” aiming to disseminate serious academic work to the wider public. Yet these efforts failed to trigger a wider debate. Furthermore, what these new reflections risk is that the critique of the mainstream and its praise of the “nation of saviors” may turn into its opposite – despising a supposed mass of “willing executioners.”

Georgi Medarov, Sofia University, Bulgaria

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: