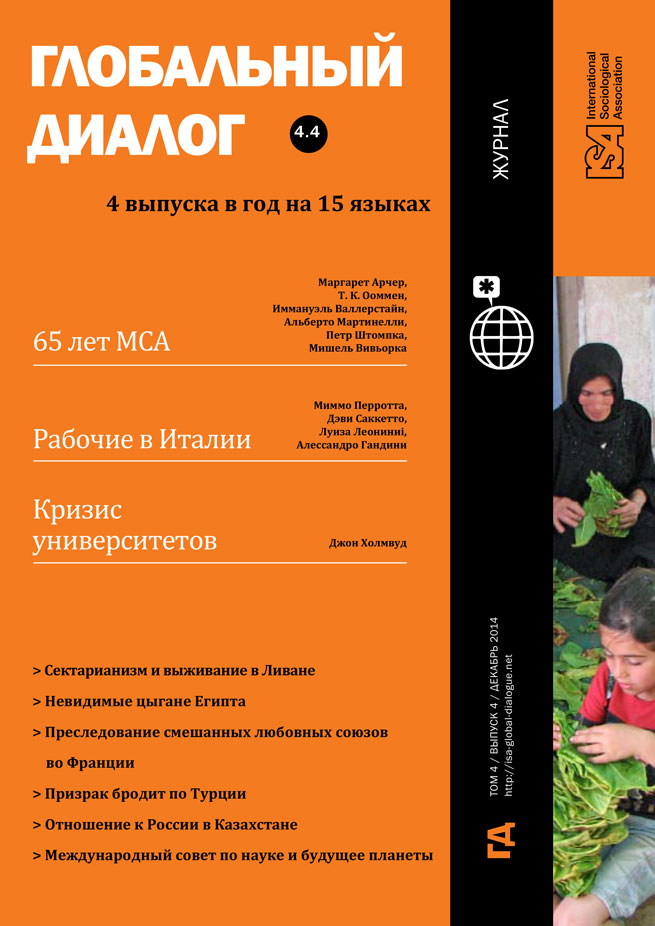

Behind the Cheap Tomato: Migrant workers in Southern Italy

December 12, 2014

In September 2013, the national French television France 2 broadcast a report about the dramatic living and working conditions of migrant farmworkers in Puglia, Southern Italy. The report, Les récoltes de la honte (The Harvest of Shame), described the harvesting and processing of broccoli and tomatoes, grown in Puglia and sold in French supermarkets such as Auchan, Carrefour, and Leclerc, and reminded French consumers that their food is cheap because of the low wages of those farmworkers.

Other European media have similarly focused on migrant farmworkers in Southern Italy. In Norway, a campaign was launched against the exploitation of Puglia’s tomato harvesters, which pushed Norwegian unions and supermarket chains to ask Italian trade unions and growers’ unions to promote “ethical standards” in agricultural production. The British magazine The Ecologist published two interesting investigations. The first, in August 2011 described the supply chain of “pelati” (whole peeled canned tomatoes): tomatoes are harvested in Basilicata by African manual pickers, processed by companies such as Conserve Italia and La Doria, and finally sold by British supermarkets (Sainsbury’s, Waitrose, Tesco, Morrison’s). The second, in February 2012, analyzed the situation of citrus pickers in Rosarno (Calabria), calling on the Coca-Cola company and its controlled brand Fanta Orange to publicly declare the price they pay to Calabrian traders for oranges.

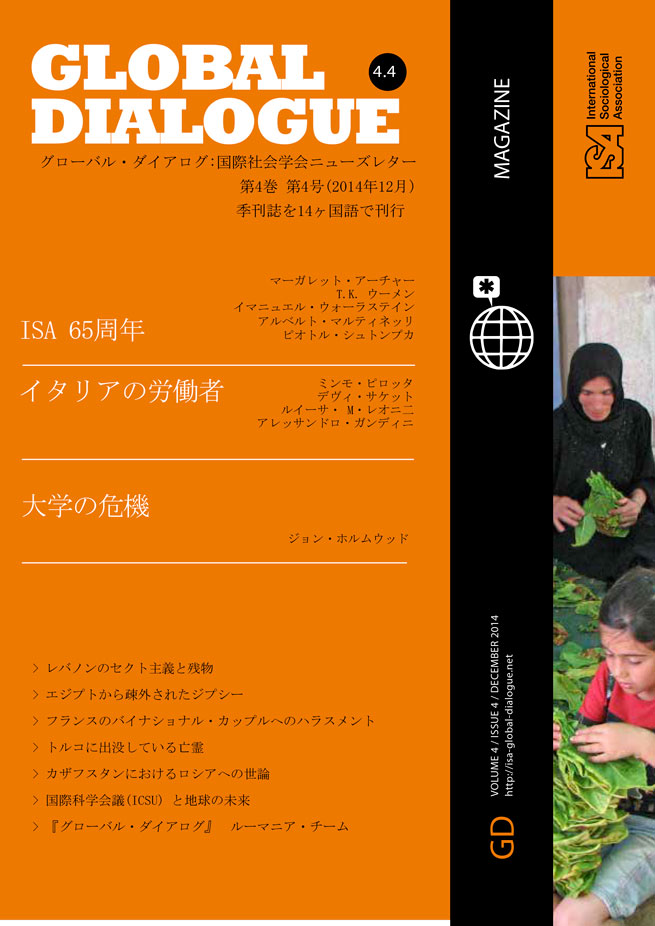

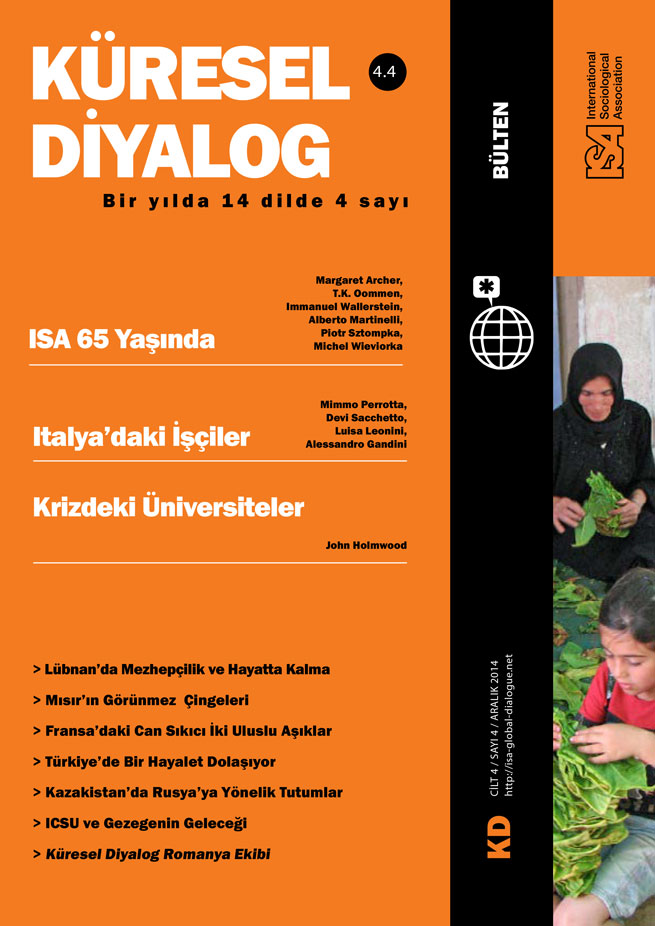

According to these journalistic reports, Southern Italian agriculture is characterized by low wages, by despotic labor control over farmworkers forced to live in abandoned houses in the countryside or in large ghettos and shantytowns, by semi-legal work, by the pervasive presence of farm labor contractors (called caporali), and by downward pressures on the prices of agricultural products and constraints on local growers imposed by traders and large-scale supermarket chains. In reality, the working and living conditions of migrant farmworkers are not much better in other European countries: migrant workers in agriculture experience difficult conditions across the continent, as European agriculture emulates the “Californian model” of intensive agriculture – with intensive exploitation of immigrants.

Since the 1970s, Southern Italy has become a destination region for foreign immigrants. In agriculture, according to official figures, there are around 110,000 foreign workers in southern Italy, and at least that many irregular workers: Tunisians and Moroccans (mainly in the greenhouses in Sicily and Campania), Indians (mainly in the livestock farming), sub-Saharan Africans and Eastern Europeans.

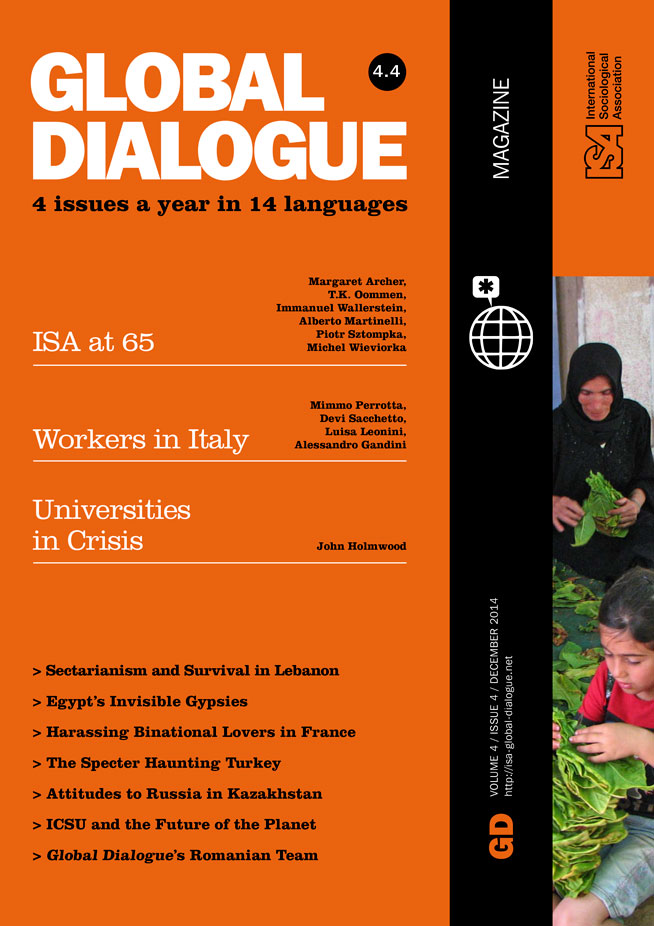

The Puglia and Basilicata regions, where I have conducted field research, both experience peak labor demand for tomato farming between June and October, especially at harvest time. The tomatoes will go to canning plants in Campania, to be turned into pelati, one of Italy’s best-known and most exported food products. Every summer, between 13,000 and 20,000 migrants, mostly from sub-Saharan Africa and Central and Eastern European countries, come looking for work. Some sub-Saharan African farmworkers have survived terrible journeys through the Sahara desert and across the Mediterranean Sea; many follow the harvest cycle across Italy’s southern regions, picking Calabria’s citrus fruit in winter, and Campania’s strawberries in the spring. Other African farmworkers hold residence permits, having worked for years in factories in Italy’s North. Fired after the economic crisis, now they struggle to find work on Southern Italy’s farms.

East Europeans are often permanent residents; Romanians are the largest group of foreign nationals in Italy. During periods of peak labor demand, many of them move to the South temporarily, from other parts of Europe, or from their home country, returning home once the tomato harvesting season is over. During the harvest period, seasonal workers live in ghettos in the countryside. Aside from occasional “humanitarian interventions,” they rarely interact with trade unions or local institutions; once the season is over they move on to other ghettos, in other regions.

Accommodation and employment of migrants are often organized by caporali, the informal farm labor contractors, often of the same nationality as the farmworkers, who ensure that crews are efficiently taken “just in time” to the businesses that require them. The caporali provide services to both farmworkers and their employers: they provide (temporary) accommodation during harvest time, transportation to fields, railway stations and supermarkets, as well as food, water and credit.

Most importantly, the caporali supervise work, and employers pay the caporale rather than individual farmworkers. For each 300kg container of tomatoes harvested, the caporale receives between 3.5 and 6 euros; he then pays workers – after he deducts a broker’s fee, the cost of transport to the fields and whatever workers owe for accommodation, food, water, and credit. Under this piece-rate system the strongest and most experienced pickers can earn up to 80-100 euros per day, but the slowest get only about 20 euros.

Caporali derive their power (and profit) from the segregation of the workforce and from the absence of “competitors”: in contrast to other parts of Italy and Europe, government interventions like seasonal labor quotas, public job centers or “formal” private intermediaries (cooperatives, temporary employment agencies) have little impact here. The economic crisis has intensified competition between workers from different countries and with different legal statuses, a fact which also makes it hard to organize collective forms of action.

Workers have different strategies for dealing with poor working conditions, despotic labor control and low wages. Romanians’ and Bulgarians’ most profitable resource is their mobility: because they have freedom of movement in Europe, they can go back and forth from Eastern Europe – where the cost of living and wages are still lower than in Western Europe – and can move elsewhere to look for other work. By contrast, African migrants’ more precarious legal status creates many challenges, including workplace conflicts, “ethnic” conflicts (such as the “Rosarno revolt” in Calabria, January 2010) and union conflicts (such as the strike held by foreign farmworkers in Nardò, Puglia, in 2011).

In 2014, all these conflicts, along with the campaigns by Europe’s mass media, NGOs, militant networks and migrant advocacy associations, have prompted regional administrations in Puglia and Basilicata to make promises of hosting farmworkers in reception centers, encourage companies to hire farmworkers through public job centers, and create new “ethical” brands for processed tomatoes and other agricultural products. During the tomato harvest in 2014 these interventions failed: once more, the farmers preferred to hire their harvesters through the mediation of the caporali and very few among the seasonal workers wanted to be “hosted” in the reception centers for fear of losing the employment guaranteed by the caporali in the ghettos.

Mimmo Perrotta, University of Bergamo, Italy <domenico.perrotta@unibg.it>