Read more about Special Columns

Chinese Edition of Global Dialogue

by Jing-Mao Ho

October 28, 2017

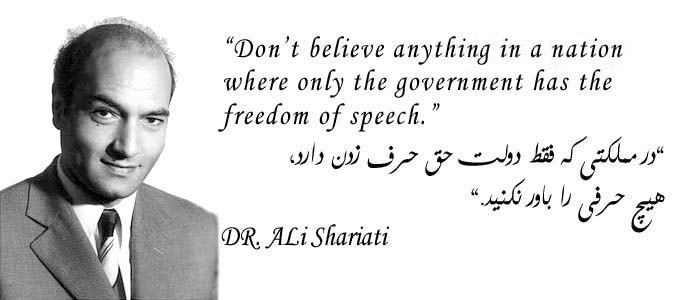

Ali Shariati (1933–1977) is widely regarded as the Voltaire of Iran’s 1979 Revolution. He was born into a religious family, received his doctorate in 1963 from the Sorbonne’s Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines, and died in England in 1977. In Paris, Shariati enthusiastically read western socio-political thought and philosophy and was highly influenced by Karl Marx, Jean-Paul Sartre, Georges Gurvitch, Frantz Fanon and Louis Massignon. He was widely admired in pre-revolutionary Iran where he was considered to be a peripheral enfant terrible – a “troublesome Islamic Marxist” who needed to be silenced. His uniqueness lies with the way he threaded religion onto other intellectual legacies.

Dr Ali Shariati was one of many Muslim intellectuals who sought to provide answers to the problems confronting Muslims in the modern, Western-dominated world. In his view, a new cultural reorientation that recognized individual agency and autonomy could help Muslim societies overcome the structural causes of their stagnation and underdevelopment. In his anti-colonialist discourse Shariati underlines the role of religion in liberating society. Echoing Frantz Fanon in his call for a “new man,” Shariati called for “new thinking,” a “new humanity,” and a more humane modernity that did not seek to turn the Third World into another Europe, United States, or Soviet Union.

As one of the most influential Muslim thinkers of the twentieth century, Ali Shariati had a major role in articulating a religiously-inflected discourse of radical social and political change in Iran during the 1960s and 1970s. For this reason, many scholars see Shariati as an advocate of political Islam. Viewing the role and function of religion in a sociological context in line with Max Weber and Emile Durkheim was one major source of separation between Shariati and the ulama. A very large section of Shariati’s work is concerned with Marxism. He used Marxist concepts such as historical determinism and class struggle to “re-interpret” Islam. This “theological Marxism” or “theologized Marxism” is Shariati’s most innovative intellectual contribution. For him, a retooled version of Islam was needed to succeed where Marxism appeared to have failed.

In Shariati’s view, religion as a movement is a modern school of thought/ideology and religion as an institution is a collection of dogmas. In Religion against Religion Shariati accused the clergy of monopolistic control over the interpretation of Islam in order to set up a clerical despotism; in his words, it would be the worst and the most oppressive form of despotism possible in human history, the “mother of all despotism and dictatorship.” Shariati himself stressed these differences emphatically: “Religion has two aspects; one is antagonistic to the other. For example, nobody hates religion as much as I do and nobody harbors hope in religion as much I do.” Shariati succeeded in producing a radical layman’s religion that disassociated itself from the traditional clergy and associated itself with the secular trinity of social revolution, technological innovation, and cultural self-assertion.

Shariati believed that social change would be successful if enlightened thinkers, the intelligentsia, realized the truth of their faith. The intelligentsia, Shariati argued, were the critical conscience of society and were responsible for launching society’s renaissance and reformation. As such, the young Shariati favored the concept of “committed/guided” democracy. In Community and Leadership he advocated the idea of “committed/guided democracy,” meaning that intellectuals are obliged to raise public consciousness, and guide public opinion in the transitional period after the revolution. Being a social activist, he always conveyed the message of social justice and tried to create societies based on egalitarianism. For Shariati, existing democracies are minimalist. Shariati’s maximalism calls for a radical democracy.

Shariati’s strong egalitarian leanings and constant critique of class inequality made him a socialist thinker. However, for him socialism is not merely a mode of production but a way of life. He was critical of a state socialism that worshipped personality, party, and state and proposed a “humanist socialism.” According to Shariati, the state’s legitimacy derives from public reason and the free collective will of the people. For him, freedom and social justice must be complemented with modern spirituality. His trinity of freedom, equality, and spirituality is a novel contribution to the idea of an “alternative modernity.”

Shariati’s legacy and his contemporary followers have contributed to a deconstruction of the false binaries of Islam/modernity, Islam/West, and East/West. In advocating a third way between these two extremes, Shariati’s thought finds common ground with other contemporary reformism including the Islamic liberalism of Abdolkarim Soroush, and Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na’im. Ali Shariati’s contributions to sociology take as their premise the continued dominance of Western civilization in non-Western societies. Many of his writings stay as relevant and useful in contemporary world as they were when they were first written.

Suheel Rasool Mir <mirsuhailscholar@gmail.com>

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: