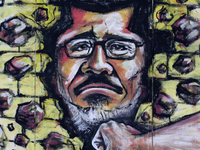

The first grand phase of the Egyptian Revolution is over: the period between February 11, 2011 and August 14, 2013 signals a clearly defined period. It begins with the apparent collapse of the old regime. It ends with its return, thirsting for revenge, but with a twist: now it claims to act on behalf of the revolution. An apparent majority of the population became disgruntled with the short-lived rule of the Muslim Brotherhood. That served as a basis for the military intervention that deposed the first democratically elected president in Egyptian history.

However, it is not at all clear that ordinary individuals who had supported the removal of Morsi actually wanted the bloodbath of August 14, when the military wiped out two pro-Morsi camps, killing nearly 1,000 people, or the two other smaller massacres preceding it. Nor is it clear they wanted the military to try to control the country even more tightly than it had under Mubarak, as it seems to be trying to do now. After all, there is nothing in Mubarak’s 30 years that resembles the atrocities committed by the military regime now in power. Nor did the Mubarak era witness such a uniformly pro-regime press. Two thirds of Egypt’s provinces are now ruled by high-level military or police officers. Most remarkable is how the security apparatus of the old regime came back to life with such full force, even though there had been little signs of it for two and a half years. It is as if the old state simply had gone so deep underground that no one suspected that it existed anymore, only to resurface with all its full murderous potential at the appropriate moment. It is an apparatus that thrives on violence: it has tried its best to encourage its opponents to become violent, so as to justify deploying the full force of the security state.

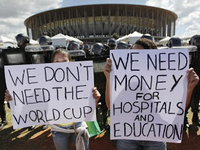

The complex dynamics of the Egyptian Revolution cannot, however, be summarized in terms of struggle over state power. Indeed, most revolutionary energy since January 2011 has been discharged against the state, rather than as demands for a specific person or party to take it over. This popular attitude, rooted in ordinary anarchist propensities[1], has been understood neither by organized political parties nor by the military – the forces that have been struggling to take control of the state. Indeed, one of the least noted properties of the Egyptian Revolution is its dual sources of dynamism: on the one hand we have street dynamism, not led by any force but rooted in old techniques of living outside of and in spite of state impositions. On the other hand, we have the organized forces – notably the Brotherhood and the military, but also the organized liberal parties – that see in street dynamism only political opportunities for their own agendas, and not as a grand revolutionary spectacle heralding a new age and new ways of thinking. Indeed, one is struck by the intellectual mediocrity of Egypt’s political elite, evidenced in the sclerotic composition of the current government, in its uninspiring roadmap to democracy (which had already been proposed almost verbatim by the deposed president), in the unreadable quality of the media it sponsors, and in the countless low-grade conspiracy theories it had spun out during this crisis.

The Egyptian Revolution, like all recent Arab uprisings, was largely a movement of ordinary individuals. By “ordinary” I mean individuals who had no elaborate ideological commitments and no party affiliation; and those who before January 2011 almost never took part in street political protests, and rarely voted in elections. These revolutions of ordinary individuals did not rely on guidance from charismatic leaders or hierarchical organizations. To their participants they confirmed that the little person is now the agent of history. While this novel feeling has led to a vastly enriched culture of engagement, including much artistic creativity and highly dynamic debating and conversational environments everywhere, it has not generated a state that resembled or at least was itself inspired by this social dynamism from below. It seems that for most ordinary Egyptians, what they wanted out of their revolution was a state that lived with them rather than simply ruled them. But the Egyptian state has rarely been run according to this expectation, and after the August massacre it is even further away from such imaginings.

The current power-holders in Egypt capitalize on an unforgiving environment of polarization, which was the ultimate source of the August massacre. While that environment tends to benefit any government that promises to be strong enough to protect one party against another, it is also an environment that is conducive to politics being understood largely as the art of eliminating the adversary. This logic has produced several confrontations, paving the way for the large-scale slaughter on August 14: a crime against humanity, justified as “the will of the people.” The Wafd Party, among other liberal forces, immediately endorsed the horror, with the argument that the security forces simply took up the task delegated to them by “the people,” who presumably turned out on July 26 to support General Sisi’s request that they give him a mandate to combat “terrorism” (by which he must have meant something like one third of the population).

But even if what happened on August 14 were the will of “the people,” it would still be crime against humanity. Such a crime begins with the usual preparation: dehumanizing the enemy, which the Egyptian media and some Egyptian intellectuals have been doing ceaselessly, so that a bloodbath appears justifiable and rational. Second, this crime requires a certain approach to political life: a belief that politics is the art of eliminating one’s enemy, completely. And third, a belief that such a task can indeed be accomplished. All three ways of thinking have been in abundant supply in recent months. But especially since July 3, I have been hearing enemies of the Brotherhood saying that this was the moment to finish off the movement once and for all. Thus, a crime against humanity is in the final analysis an act of superstition: a belief that a little bloodbath will solve a problem we do not wish to understand. If revolutions are served by reason, as Herbert Marcuse understood already in 1940, they are undone by superstition, from which they must, in turn, be saved.

[1] See Bamyeh, Mohammed A. (2013) “Anarchist Method, Liberal Intention, Authoritarian Lesson: The Arab Spring between Three Enlightenments.” Constellations 20(2): 188-202.

Mohammed A. Bamyeh, University of Pittsburgh, USA, and Editor of the ISA’s International Sociology Reviews