Read more about Struggles over Abortion in Poland

Towards An Illiberal Future: Anti-Genderism and Anti-Globalization

by Agnieszka Graff and Elżbieta Korolczuk

February 17, 2017

In autumn 2016, a new wave of women’s protests broke out against the planned criminalization of abortion in Poland. Polish feminists have fought against Poland’s anti-abortion law since draconian legislation was introduced in 1993. The Polish abortion law, one of the strictest in the European Union, allows abortion only in cases of incest or rape, threat to health and life of a woman, and fetal genetic distortion.

As Polish activists have pointed out, the legal restrictions have spawned an underground abortion network in the country, but the issue did not gained momentum until 2016. After Poland’s 2015 parliamentary elections gave the right-wing Law and Justice Party a parliamentary majority, it was only a matter of time before more restrictions on reproductive rights would be proposed. In early 2016, government leaders, including Prime Minister Ms. Beata Szydło, signaled their support for a total ban on abortion, while a very conservative NGO, Ordo Iuris, started collecting signatures in support of prison sentences for both women and gynecologists, and demanding that authorities investigate to ensure that apparent miscarriages were not induced by medical abortifacients.

The outrage provoked by Ordo Iuris’ new campaign quickly translated into two activist campaigns: demonstrations and pickets organized by the newly-formed Girls for Girls, a grassroots organization with a feminist agenda, and a legislative initiative Save the Women, taken up by a group of social democratic feminists who campaigned to liberalize Poland’s anti-abortion law.

In mid-2016 Ordo Iuris announced it had collected over 500,000 signatures in support of its proposal, while Save the Women had collected 250,000. Both proposals were submitted to the parliament. Right-wing Catholic organizations had submitted several similar proposals in previous versions, but these had been outvoted; no pro-liberalization proposal had been submitted since the early 1990s, when a pro-liberalization petition signed by 1.2 million citizens was rejected.

This time, parliament immediately rejected the Save the Women project, instead continuing to discuss the criminalization proposal – a move that provoked demonstrations by Save the Women, and by the left-wing Razem party, which called on supporters to dress in black and join pickets or to post photos in social media, using #blackprotest as the hashtag. When one of Poland’s most respected actresses suggested an all-Poland women’s strike, modeled on a 1975 strike by women in Iceland, social media activists jumped on the idea, announcing that October 3 (2016) would be the date for an All-Poland Women’s Black Protest Strike. The call for action was not initiated by any of the women’s organizations, although many activists from feminist movements and political parties supported the initiative by offering their time and resources to the effort. In the days before the strike, many individual private employers, and local government officials expressed support for women who wanted to strike, literally telling employees to take the day off on October 3. Some university faculties called off lectures.

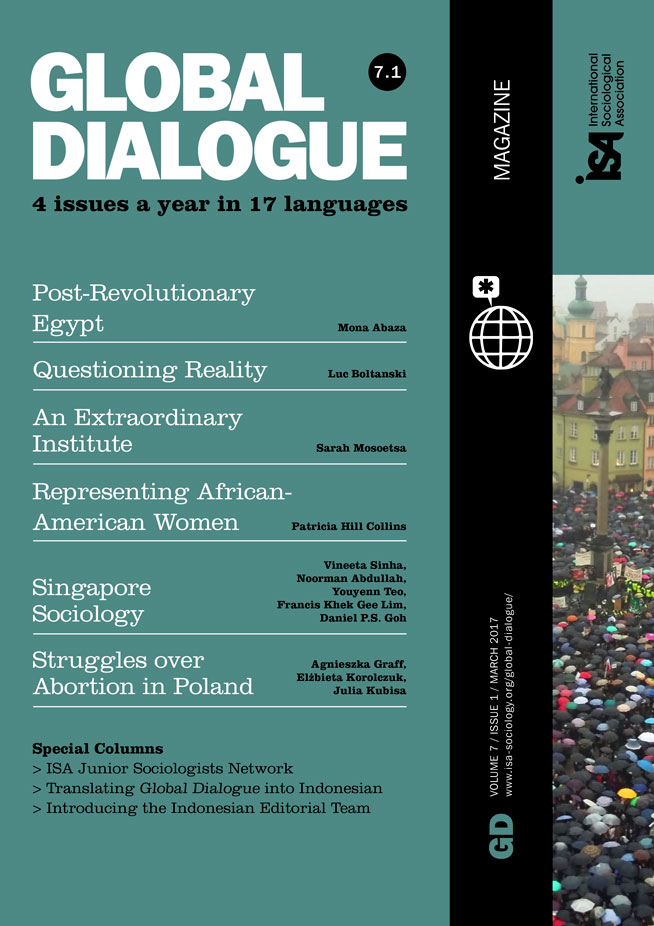

Despite obstacles, such as the strike’s legal status, it proved to be a major success, with unprecedented levels of mobilization. Unlike the demonstrations that take place in the capital and other big cities, the Women’s Strike was genuinely supported throughout Poland. Women and girls, with some supportive men, organized actions in at least 142 cities and villages all over the country, involving roughly 150,000 people – all dressed in black. The slogans referred to basic women’s rights, reproductive choice, and women’s dignity, which would be violated by a total ban on abortion. Because it rained heavily on the day of the strike, most participants stood and walked under umbrellas, which became an unexpected symbol of protest.

The scale and energy of the protest clearly took the ruling party and officials of the Catholic Church by surprise. The first responses were explicitly misogynist: a Catholic bishop claimed that women “cannot conceive during rape,” a populist politician insisted that women are sexually promiscuous and must be controlled, and the Minister of Foreign Affairs called women completely irresponsible. Nevertheless, three days after the protest, the parliament rejected the proposal for a total ban of abortion – one of the very few recent defeats for Poland’s ruling party.

The government dropped its confrontational rhetoric, instead adopting a “soft-core” approach. The Prime Minister announced that Polish women who experience a “difficult pregnancy” – a euphemistic term, “difficult” referring to cases of incurable illness or fetal distortion discovered during pregnancy – would receive a one-time benefit of about 1,000 euros, basically a benefit for giving birth to a child that will die soon after birth. The benefit has already been introduced, despite criticism that it objectifies women.

Many of the activists involved in organizing the All-Poland Women Black Protest Strike decided to continue, so the government would still feel pressure. Two weeks later, they organized another strike action that was smaller, but which brought forward an eleven-point agenda, promoting women’s dignity and freedom, opposing sexual aggression, domestic violence, and militarization of society, and calling for a more women-oriented social policy. The Black Protest inspired at least two celebrities to discuss their own abortions in public, breaking a taboo in public discourse. The Black Protest gained significant public recognition, with 58% of Poles expressing their support. It also gained wide international recognition, inspiring women in Argentina, Iceland, and South Korea to organize similar protests. Barbara Nowacka from Save the Women and Agnieszka Dziemianowicz-Bąk from Razem were granted the Global Thinkers 2016 Award by Foreign Policy magazine as the representatives of Women’s Black Protest Strike movement.

Poland’s government has continued its softer approach since the strike, dropping any reference to further restrictions on abortions, and instead promoting a discourse of support for children born with disabilities – although it has taken no real steps to increase funding along these lines. But the feminist activism that produced the nation-wide strike in October continues to reverberate: recently, when the Ministry of Health lowered national standards for birth and maternal care in hospitals, and the ruling Law and Justice party revealed that it plans to reject the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, the women linked to the All-Poland Women’s Strike declared they “will not fold their umbrellas.”

Julia Kubisa, University of Warsaw, Poland <juliakubisa@gmail.com>

This issue is not available yet in this language.

Request to be notified when the issue is available in your language.

If you prefer, you can access previous issues available in your language: