The Strange History of Sociology and Anthropology

November 01, 2015

In the early twentieth century, the founding father of the social sciences in the Netherlands drew a line between sociology and anthropology. While anthropology would study the “less advanced” peoples, sociology would focus on the social organization of the “more advanced” societies – who all happened to be located in the West. This clear divide, however, soon proved all too simple.

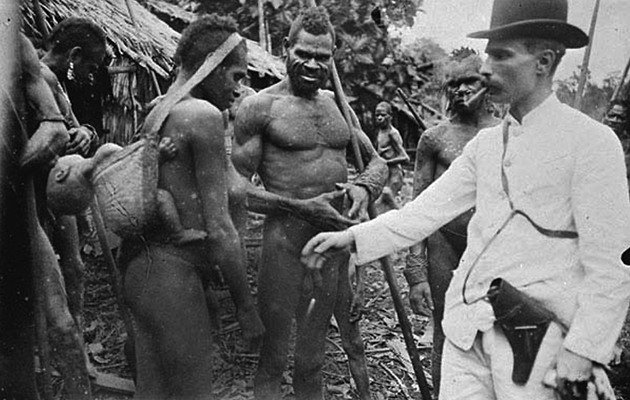

From the seventeenth century onwards the Netherlands had built up a colonial empire; ruling overseas territories required knowledge of the social structures and culture of their population. Living in large-scale, multi-stratified and literate societies such as the East Indies, they were called natives rather than aboriginals (a label reserved for small and stateless tribal bands roaming around in their remote and unwieldy habitat as our primitive ancestors). The initial idea that colonies were for the benefit of the metropole, justifying the draining away of any surplus that could be tapped, had to be rephrased. Colonialism came to be portrayed as a civilizing mission.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, foreign domination was justified as guardianship, helping colonies to progress; the famous mise en valeur thesis promised to bring value where it was absent. The role of the Dutch colonial sociologist became similar to that of the British government anthropologist in colonial Africa: to advise authorities on the impact of policies, or to offer advice on how to keep the rising fervor of the Islamic movement in check, how to find out who was behind social revolts or, the question which obsessed colonial policy makers, how to make Javanese peasants imbibe the spirit of capitalism. The civilizing mission proclaimed that “where the natives are now, we were once; what we are now they are bound to become.” In order to realize the pledge of imitative transformation, the colonized mass had to be cut loose from their own past and identity, and recast as people without history.

Was the white man’s burden lifted when the freedom struggle put an end to colonial rule in the mid-twentieth century? Arguing that any scientific wisdom gathered on native custom and lore in the faraway domains should not be wasted, Dutch politicians authorized a few universities — Leiden and Amsterdam in particular — to establish chairs and courses in what was termed “non-western” sociology, dealing with the complex societies of former colonies. It was an odd label, since it declared what these societies were not but might become, passing through a route described as transitional. Seen as a separate discipline, “non-western sociology” was ranked between anthropology (devoted to tribal societies in such places as Papua New Guinea and Surinam) on the one hand and (western) sociology on the other hand. Unique to the Netherlands, it was actually an expression of parochialism, denying the universalizing agenda of scholarship put forward by thinkers like Weber, Tönnies or Durkheim.

This western-centric bias allowed practitioners of sociology to turn their backs on what came to be understood as the third world: they could restrict their craft to the study of “modern” society in the global North. The civilizing mission endured, however, in the postcolonial era, expressed in a formal commitment to help “backward” countries in their attempt to catch up with “lead” nations. The awkward designation “non-western” – which put very diverse peoples and cultures under one heading – was now replaced by a more appealing manifesto, which aimed to promote development where it had failed to emerge, in the global South, and which gave rise to a development sociology, engaged in mapping how the rest of the world, home to the majority of mankind, would fare in the passage considered evolutionary from an agrarian-rural to an industrial urban way of life.

Meanwhile the domain of anthropology had also changed. “Our living ancestors” were no more. If not wiped out in the remote niches of Australia, Asia, Africa and the Americas when opened up in the march of progress, they were incorporated in larger state formations, losing whatever autonomy they tried tenaciously to retain. But with a different research method than sociology, anthropologists moved on, finding other sites to practice what they called “fieldwork,” coming close to the people under their lens, seeking their company and thus becoming familiar with what they were up to.

But how to draw the dividing line with sociology? The professor of anthropology at the University of Amsterdam, where I opted for Asian studies in the late 1950s, proposed that anthropology should concentrate on tradition, while modernity would be the preoccupation of sociology. That line of demarcation turned out to be a non-starter from the very beginning because it was impossible to nail down distinctive features on either side of that divide. The essential quest for both disciplines remains why, how and with what consequences processes of change evolve. They both discuss the relationship between past and present, rather than reifying the contrast opposing traditional to modern.

When I was nominated professor of comparative sociology at my alma mater in 1987 – I did not want a chair going under the name of “non-western” or “development” studies – a senior colleague and I together set up the Amsterdam School for Social Science Research (ASSR), with a PhD program that aimed to bring together sociology, anthropology and social history to promote research in a historical perspective on the dynamics of globalization. Although our academic exploits were quite successful, we were unable to persuade either the national sponsoring agency or the Board of the Amsterdam University to provide adequate funding for the program. Due to this critical lack of support, the ASSR was phased out and restructured as the Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research. The teaching staff in our faculty are split into two departments, sociology and anthropology, each with its own research profile.

Has the classical pair fallen apart again? By and large yes, since their respective focus is on the West and the Rest, the latter-day synonym for “more” and “less” advanced. The return to separation is messy on many counts but mainly because the societal and geo-political distinction between front-runners and latecomers makes nowadays even less sense than it did earlier on. The hallowed trajectory of transformation, spelling out how the lesser developed nations will catch up with the developed ones, has been obliterated. The Rest does not follow the West in many ways – and who knows, the direction and pace of change might well prove to be the other way round.

Jan Breman, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands <J.C.Breman@uva.nl>