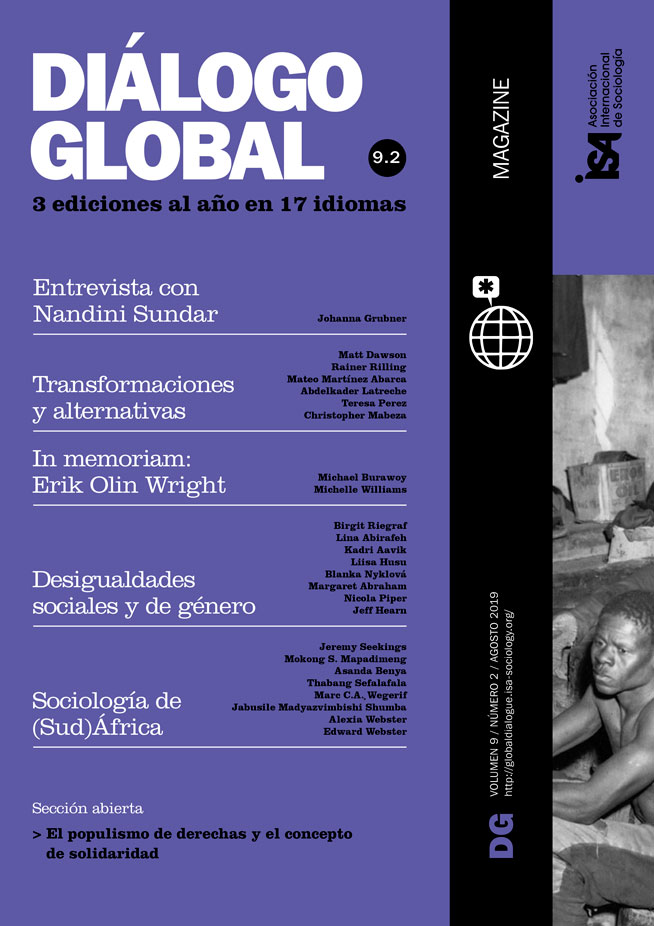

It has been fifteen years since women joined the underground workforce in South Africa’s mines. Currently there are close to 50,000 women in mining, about 10.9% of the permanent mining employees. While close to 11% of the mining workforce are women, and legislation facilitating and accelerating their inclusion has been adopted, the industry continues to imagine and present itself implicitly as masculine and depicts only men or male bodies as suitable for underground mine work. This suitability of male bodies for underground mine work is almost naturalized and eternalized, in discourse and in mining occupational culture.

The naturalization of male bodies in mining has inadvertently facilitated the exclusion of women, despite legislation that seeks to redress past exclusions. As I argue elsewhere, women in South African mines are “included while excluded.” Indeed, they are seen, to use Nirmal Puwar’s words, as “space invaders” and as such, are producing a “state of disorientation and ontological anxiety.” They have not only been accused of negatively affecting productivity and safety but have also been stigmatized both inside the mines and outside for not conforming to societal norms about femininity, and their morals have been questioned.

While in theory women can do any underground job, in reality they are barred from taking up certain jobs. In all the shafts where I conducted my research, women could not be rock drill operators, and very few were lashers or winch drivers. The few winch drivers I worked with hardly ever drove winches underground. Using protectionist discourse, mines strategically refuse to recruit, train, and allocate women to some occupations underground. This is despite the fact that protecting them from “strenuous underground jobs” also renders them financially disadvantaged since they cannot, in some instances, claim the same production bonuses as men.

Below I refer to one of many incidents underground which illustrates how the exclusion of women, wrapped in cultural and protectionist discourse, is furthered and entrenched daily with many recruited to be complicit, to cement and ingrain it while rhetorically preaching inclusion.

In the early stages of my research, while still training to be a winch driver, I was told women were not allowed in the drilling class. Reasons for their exclusion were based on their bodies, which instructors and the mine considered improper and “too fragile” for the operation of the drilling machine. Instructors argued that drilling machines would negatively affect women’s wombs. In my case, after persisting and eventually being allowed to join the drilling class, I was strictly instructed to only observe and not touch anything because “the hot stopes and drilling” were for men and incompatible with women’s anatomy. The design of the machines and the ventilation in the stope were not cited as reasons.

After a few sessions at the training center and a few days of observing, all new recruits were given a chance to try out the machines and were encouraged to imitate as closely as possible the instructors and experienced workers - from how they sit with their legs straddled across, and thighs tightly closing in on the machine, to their breathing and bodily rhythms. When it was my turn, however, the lesson was different. The instructor went from initially refusing to let me operate the machine to telling me that women cannot straddle machines. Yet, to insert the machine and be stable one has to straddle the machine.Myinstructor, however,told me to bring my legs together. He said my “legs must both be on one side, like a lady.” This is despite repeatedly seeing him shove the machine-boys down, telling them to open wide their legs, straddle the machine and feel it between their thighs and “hold it tight and push it in.” He told me to bring my legs together and move them to one side “otherwise you won’t be able to have babies… you are killing your eggs.” Workers also remarked that a woman straddling a machine looks “indecent.”

As expected, when I followed their instructions and drilled “like a lady” with both legs on one side, the machine dragged me. When I switched it off to tell them that it is impossible to drill in that position, before I turned my head back to them, the instructor said “you see I told you that women cannot drill, I’ve been in mining for a loooong time, I know what I’m talking about. Women cannot do this, it’s impossible… this machine is heavy” (all the workers I could lay my eyes on were nodding in agreement) (Field notes, Rustenburg, April 2012). For these men, my being dragged by the machine was a confirmation of the “unsuitability” of women’s bodies for drilling, not their “special” instructions against straddling the machine.

These preconceived prudish ideas about women’s bodies are not only at the training center but filter into the daily work underground. As I document elsewhere, there are many cases where women are prevented from doing their work underground, or reduced to assistants who clean and fetch water for teams, or removed from their working places and separated from their teams especially if the team works in the hot stopes. I call this the informal job reallocation and it has led to women’s isolation from their teams and alienation from their work and has had both short-term (not qualifying for production bonuses) and long-term dire effects around promotions.

These are not isolated incidents, but rather, are systemic and reinforce the peripheral status of women in mining, despite their legislated inclusion in underground work. I use the examples above to illustrate the significant and very real, yet invisible differences in how men and women are trained and treated at work and how preconceived notions about women’s bodies as fragile and weak leads to their exclusion, thus rendering them “second-class” workers underground. It is clear that legislation alone is insufficient - it is the deeply ingrained masculine occupational culture and norms that need to be challenged and changed.

Asanda Benya, University of Cape Town, South Africa <asanda.benya@uct.ac.za>