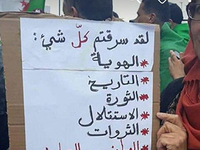

Last month I finished packing the last of my belongings to move back to the UK after seven years in Cape Town. Anything that I didn’t want was placed outside my home and gone within an hour. Waste pickers had collected, sorted, and sold my things. This for me was a fast and convenient way to minimize waste, while simultaneously supporting people to generate an income. For others, I was being irresponsible by attracting and encouraging homeless people to the neighborhood, who no doubt spent the money on alcohol and illegal substances. Neighbourhood watch groups would express little wonder at the burglary next door a few weeks later: these so-called “waste pickers” are the eyes and ears of criminals.

Such polarized attitudes can be explained by the way that policies have yet to overcome the stigma faced by waste pickers. Negative stereotypes affect the likelihood of waste picking becoming a “green job” or of waste pickers becoming employees in the recycling industry. The phrase “waste picker” has negative connotations, which has led to calls to use other words such as “reclaimer.” My use of “waste picker” echoes language used by the South African Waste Pickers’ Association (SAWPA) and the Global Alliance of Waste Pickers, who advocate for better working conditions. Despite their efforts, there is no consensus about the circumstances (if any) under which waste pickers should be supported.

Policy and image

Ambiguity about waste picking is exacerbated by the variety of positions taken at different policy scales and between regions. At a global level, waste picking falls under the International Labour Organization’s “decent work” agenda. Waste pickers are portrayed as important in achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals. This means waste pickers are potential workers in the green economy in the global South. Unlike their counterparts in the global North, sometimes known as freegans or dumpster divers, waste pickers are not aligned with environmental movements. Waste pickers are rarely seen as people making an active choice and instead are associated with desperation. This image is significant at a national level. On the one hand, governments can opt for more labor-intensive methods of minimizing waste that could employ waste pickers, but are indicative of high levels of poverty. On the other hand, they can pursue technological solutions such as “waste-to-energy” that emulate modern European methods, but create fewer jobs and are unlikely to be filled by people currently working as waste pickers.

Cape Town became home to Africa’s first large-scale waste-to-energy plant in 2017. In light of electricity shortages and the return of regular outages at the time of writing this piece, any alternative to the nationalized utility provider (Eskom) is an easy sell. A further benefit espoused at the plant’s launch was that workers (approximately 80) would not have to pick through waste like those at rubbish dumps. In fact, unlike other local governments that have helped waste pickers to form cooperatives, waste picking at landfill sites is outlawed in Cape Town. This variation within South Africa is possible because, although national legislation (The Waste Act) stipulates that local governments must have a waste management plan, the means of achieving zero waste is entirely at the discretion of local policy makers. In urban areas striving to become “world cities,” a modern image is important for attracting foreign investment. Street waste pickers are removed from central business districts in preparation for high-profile events such as hosting the FIFA World Cup. Any street-level reclaiming tends to be viewed by local officials as voluntary but is largely discouraged. This is in part due to residents’ complaints, especially in historically “white” suburbs where residents connect grime with crime.

Residents’ perceptions

The expansion of green jobs involves public participation. The success of curbside collection schemes relies on residents separating their waste and being happy for former waste pickers to access and sort through their household refuse. At the moment, waste pickers struggle to present themselves as potential workers and what they do as a public service. There is an air of suspicion around who these people are that sift through bins, and what their motivation is. Based on looks alone, waste pickers are no different from destitute vagrants. Often labelled as “bergies,” it is assumed that rifling through bins is a last resort for people who have severed their ties with friends and family, relationships that “normal” people would be able to rely on in times of need. Waste pickers’ physical appearance can also add to a sense that they are not trustworthy. Many waste pickers have prison tattoos, scars, and other physical signs that serve as discrediting markers. This makes it difficult to present themselves as people who have successfully exited out of crime by making a job for themselves. Instead, waste pickers appear somewhat unapproachable. The lack of interaction means residents rely on other sources of information to judge waste pickers.

In affluent suburbs, private security firms fuel prejudice and discrimination by advising against giving to waste pickers; this feeds the sense of fear that their business relies on. Similarly, neighborhood watch groups are unable to differentiate between people trying to make a living and someone about to break into their house. Residents have joined with councilors to create street patrols that practice profiling according to “race,” age, and gender, reporting and removing anyone regarded as a threat to safety and security. Residents’ WhatsApp groups use “BM” as a code for “black man” to keep track of the undesirable types of people seen in the neighborhood. Street waste pickers must therefore continually negotiate and re-negotiate their access to streets and household rubbish. As it stands, waste pickers are unlikely to be perceived as potential service sector workers by the general public. Other than pockets of government support in parts of South Africa and the work of advocacy groups, waste pickers have remained marginalized. Therefore policies aimed at helping waste pickers to form collectives or become employees, as seen in parts of South America, do not reach people who are stigmatized as a nuisance.

Exacerbated by inconsistent policies at the global and local scales, stigma is a constraint for waste pickers in South Africa. Pervasive stereotypes, entrenched by historical disdain for unregulated (non-European) workers, prevents them from gaining the level of support required for their participation in the green economy. Waste pickers are interpreted as vagrants, dependent on alcohol or illegal substances, incapable of rational thought, and a threat to safety and security in affluent suburbs. Waste picking is seen as backward, dirty, and an inefficient way to minimize waste. This negativity persists all the more in light of policies that annex waste pickers and waste picking as signifiers of being a developing country. Hence, in cities conscious of attracting tourism and business, mechanized forms of recycling are likely to remain more popular than their labor-intensive counterparts.

Teresa Perez, University of Cape Town, South Africa <tpz031@googlemail.com>